To Prohibit, To Punish, To Disappear: The Mexican State and the Fiction of Public Health

ACT I

The chamber’s cold lights carve angular shadows on faces caught in perpetual motion: clenched jaws, arched brows, fingers tapping a quiet impatience onto official papers. Everything obeys the choreography of protocol. Microphones flicker on. Ties are straightened. Eyes scan with the studied focus of those who’ve mastered the art of appearing spontaneous. The murmurs don’t disturb the ritual; they consecrate it.

Chambers like this have long learned to worship the spectacle of power. In liberal democracies, performance has become a ritualized routine years ago. At center stage, a senator raises her voice to recite the newest amendment to the General Health Law: “The production, commercialization, distribution, and sale of electronic cigarettes is hereby prohibited throughout the country…”

She pauses —deliberately.

Her gaze sweeps the room.

She knows: the numbers are locked in.

Seventy-six in favor. Thirty-seven opposed. Applause, measured and brief. One adjusts his glasses. Another is already declaring victory on social media.

But what, exactly, has been outlawed?

A sweet haze that disappears like a whisper. A promise suspended in vapor: relief, control, autonomy, a fragrant detour from tobacco. More than an object, it is a portable ritual: of identity, of escape, of breath reclaimed.

Now, the State dons its sanitary robes and renders its verdict:

You shall inhale no more.

ACT II

The backpack thuds against the packed dirt, squeezed between two crates of sun-warmed strawberries. The young man who dropped it, twenty-two, Pumas jersey, an accent weathered by the city’s frayed peripheries, smiles with the instinct of someone who once hawked candy at red lights.

But what he’s offering doesn’t melt in your mouth. Imported vapes, origin vague, destination precise; each one laced with flavors bordering on the fantastical: Glacial Dragon, Explosive Mango, Atomic Cherry.

“It’s banned, so now it’s worth more,” he says, eyes flicking across the street like antennae. He speaks with the confidence of someone fluent in the underground grammar of scarcity.

These devices circulate like shadow currency, untaxed, uninspected, unregulated. What remains is pure margin: five million units a month.

That’s the new arithmetic of a market reborn in the vacuum left by the state. Behind him, spray-painted on a crumbling wall, the graffiti isn’t ironic; it’s diagnostic: Banned, still sold.

ACT III

From the podium, a senator raises his voice in defense of the measure. He invokes “health hazards,” the imperative to protect “the children,” and leans on studies still fogged by uncertainty. Childhood and the future become his moral armor, shields held high for the cameras.

“They want to poison us,” he declares, locking eyes with the camera—a gesture calibrated down to the pixel.

The phrase goes viral.

By morning, his face dominates the front pages, flanked by images of blackened lungs, corrupted youth, and candy-colored flavors with names fit for cartoon villains.

But few paused to name what was quietly being unearthed beneath the surface of legality: a wide corridor opened to illegality.

A handful of opposition voices in the lower house, including PAN and Movimiento Ciudadano deputies, had warned of a lack of harm-reduction strategies and urged regulation rather than prohibition. They pointed to models in the UK and New Zealand. Congresswoman Iraís Reyes even vaped at the podium, a performative dissent meant to jar the chamber. But by December 10, when the Senate cast its vote, those gestures had already been drowned by the dominant current. Prohibition claimed the spotlight.

Offstage, only the vacuum remains.

ACT IV

At last, the Senate votes as if the air itself could be legislated. With 76 in favor and 37 opposed, the reform to the General Health Law was approved. Across the entire national territory, the ban now extends to the production, commercialization, import, export, storage, advertising, and sale of electronic cigarettes and related devices, including disposables, even those free of nicotine.

But the new legislation doesn’t just prohibit. It criminalizes.

Manufacturing, importing, or selling these devices can now lead to prison sentences of up to eight years. Fines surpass 200,000 pesos.

What was once vapor is now treated with the severity usually reserved for high crimes.

Championed by President Claudia Sheinbaum as a gesture to safeguard public health, the measure has drawn sharp criticism from opposition parties and from within the public health community itself.

Critics warn it will only fuel an already thriving black market, estimated at five million units per month, while offering no harm-reduction strategies, no regulated alternatives, and no off-ramp for smokers.

A ban with no exit. Now, it waits only for the president’s pen.

Prohibition as the State’s Native Tongue

In Mexico, prohibition is the State’s native tongue, spoken with the same fervor used to silence alternatives. The country has long stockpiled laws that sound like fortresses but behave like sieves.

In 2022, a presidential decree had already sought to block the circulation and sale of electronic nicotine delivery systems. The language was precise. The implementation, erratic. The market, indifferent.

In practice, a walk through any commercial district in Mexico City reveals the predictable outcome of prohibition without regulation: abundant supply, inventive informality, and a growing sense that the State speaks loudly but walks lightly.

The law exists. But vapor, as ever, slips through the fingers.

What has changed is the scale of punishment and its symbolism: Prohibition is no longer a decree floating in the air; it has crystallized into legal architecture. And that architecture is made of bars.

The reform imposes up to eight years in prison and hefty fines on those who manufacture or sell. It is the State attempting to reclaim authority not through intelligent regulation, but through the threat of severity.

Here, the moral fracture in the public health argument is exposed. Mexico is a country where public health coexists with structural absences: supply chain promises, large-scale medication purchases, and yet, persistent shortages.

Reforms often reshuffle essential funds. The case of FONSABI made this fragility painfully visible: regulations that once guaranteed mandatory allocations for catastrophic illnesses—like cancer—were hollowed out by legislative tweaks that expanded political discretion and eroded financial predictability.

The State finds the strength to criminalize vape sales, yet falters or outright fails when the agenda demands logistics, stockpiles, procurement, and sustained care.

Prohibition advances where care recedes. And there is a second, quieter, crueler contrast, one not heard from podiums. Mexico possesses both the literature and the data to document barriers to medical access to opioids for pain: scarcity, regulatory hurdles, chronic supply failures, especially in the public system.

In other words, a country that still fails to guarantee morphine for the dying is now prepared to expend political capital on imprisoning sellers of nicotine devices.

Where care is absent, punishment rushes in.

That sentence could already pass for a proverb in Mexico City.

It’s not that vaping is harmless. It isn’t. It’s that the tool chosen to address it, prison, reveals more about the State than about the product.

“A Gift to the Narcos”

Occasionally, someone says the unsayable. In the chamber, the line that goes viral is often the one that, stripped of euphemism, voices what everyone else is whispering.

That’s what Congresswoman Iraís Reyes (Movimiento Ciudadano) did when she called the reform “a holiday bonus for organized crime,” a year-end gift, wrapped in good intentions.

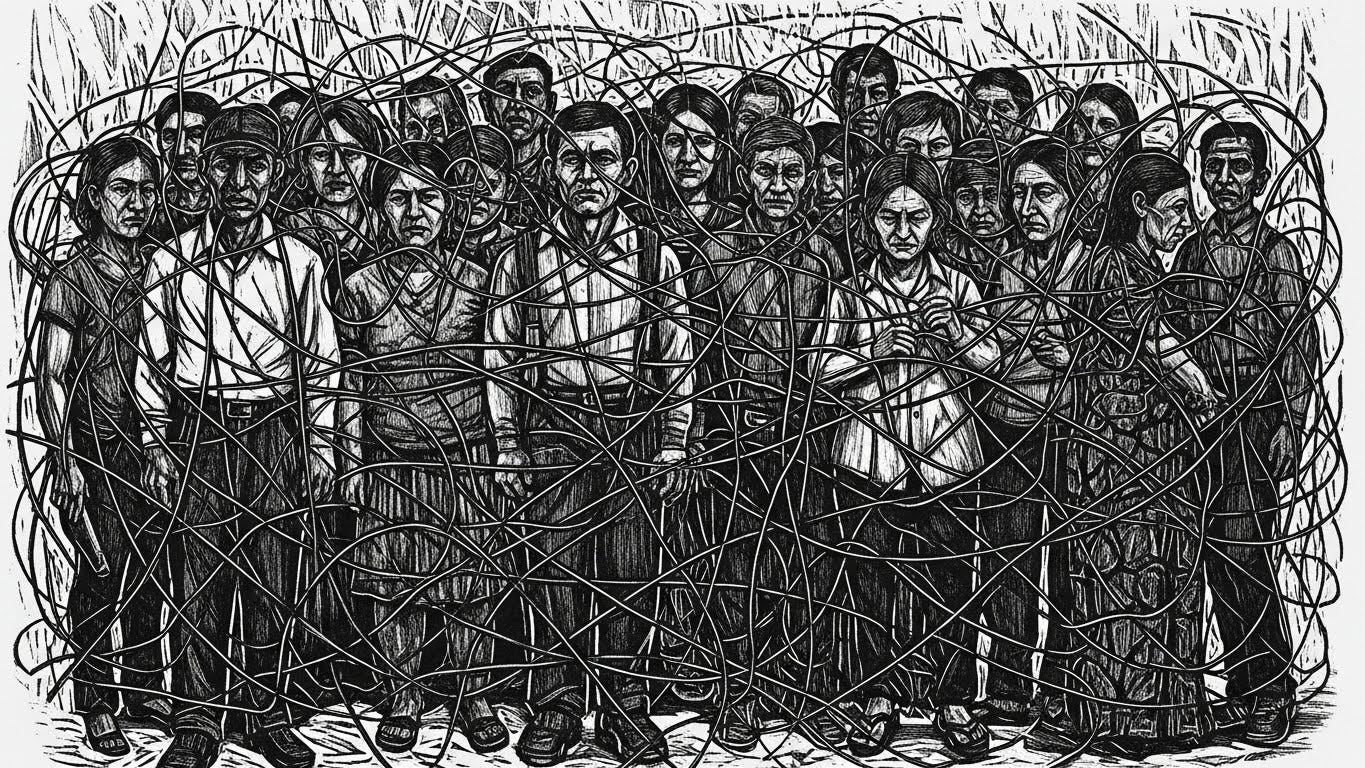

The image strikes because it’s recognizable. In a country scarred by the war on drugs, the creation of black markets feels less like a policy failure than a conditioned reflex.

On the Senate floor, Senator Luis Colosio echoed a familiar liberal refrain: banning, he argued, is “the easy way out” of a problem the State either cannot, or will not, regulate. Instead of building policy, it defaults to prohibition.

Where politics are absent, bans multiply.

These voices strike a central nerve: when an entire supply chain is outlawed, from import to advertising, the market doesn’t vanish; it merely changes hands. And in a country where the illegal economy already moves with logistical sophistication and territorial control, that shift is perilous.

A regulatory vacuum is not neutral; it’s an invitation.

And the first to RSVP is rarely the State.

The irony is evident: Mexican law already recognizes zones of tolerance in other domains of private life. Since 2009, the General Health Law has included a table of “maximum doses” for personal use of certain narcotics, a partial decriminalization mechanism aimed at users.

In other words, the State has already acknowledged that total bans are ineffective. Yet when it comes to flavored nicotine vapor, a product often used as a cigarette substitute or therapeutic aid, tolerance gives way to incarceration.

Mexico, then, knows—or once knew—how to distinguish user from supplier. In the vaping reform, that distinction survives, but with a twist: the user is spared; the intermediary is crushed.

The harshest penalties fall on the weakest link: the street vendor, the small-time distributor, the informal shopkeeper. People without lobbyists. Without institutional shields. Without an army of lawyers.

And, as always, the law doesn’t fall evenly.

It falls by ZIP code.

Selectivity as Method

Picture two young men.

One steps out of a bar in Polanco, holding a sleek, “clean” vape, bought abroad or at a shop that, somehow, remains open.

The other crosses a street in Ecatepec, a cheap disposable in his pocket, a backpack full of devices for resale.

The first will be seen, at worst, as someone with a “habit.” The second risks becoming a statistic, and a criminal case.

The opposition warned precisely about this: a sweeping ban widens the window for extortion, arbitrary confiscation, and police “bites.”

The product doesn’t vanish. It simply migrates into a gray zone ripe for abuse, as the Mexican author Iván Garay has noted.

Bans like this are ideal for manufacturing victimless crimes, infractions that require no complaint. Only a stop-and-search. A profile. A pretext. A backpack.

In the end, it’s not just about electronic cigarettes. It’s about the old reflex: to forbid before understanding, to punish before regulating.

It’s about how the State tries to reclaim authority where it has lost presence, and who ultimately pays the price for that attempt.

The user remains.

The market adapts.

The small player, the one who sells out of necessity, becomes the target.

The War Mexico Knows by Heart

Mexico knows, by heart, how moral crusades cloaked in punishment tend to end: in more clandestinity, more corruption, more violence to keep the forbidden market alive.

The vocabulary stays the same; only the object changes. Once it was cocaine. Then marijuana. Then meth. Now: a palm-sized device, passed hand to hand at college parties, glowing in TikTok videos.

The difference?

Vapes don’t need to cross jungles or slip through covert ports. They only need to remain desirable. And desire is a stubborn currency.

When the State says, “disappear,” the market answers, “multiply.”

It leaves the storefront and slips into a WhatsApp group. It trades the counter for a delivery rider. What was traceable becomes a murky, homemade mix. And in a country where prohibition has existed since 2022, and long before, while the devices never stopped circulating, the new law doesn’t sound like containment.

It sounds like the performance of resolve, dressed up as control.

What Real Public Health Would Look Like

A serious public health policy, especially around nicotine, requires three elements: restrict access for non-smokers, communicate risks with brutal clarity, and offer real alternatives to those who want to quit or switch. These pillars are always in tension, but never optional.

Some countries, contradictions and all, are moving, slowly, in that direction. The United Kingdom, for instance, treats vaping as a harm-reduction tool for adult smokers, under strict warnings and, more recently, with new limits like the ban on disposables.

Mexico, however, chose a different path: it turned public health into a matter of law enforcement. And so a familiar phrase returns heavier this time: prohibit, punish, disappear.

But this isn’t just about vapes.

It’s about the enduring fantasy that fear educates, that prison replaces policy, that bans are enough.

Underground, life goes on. Vendors unzip their backpacks. Users keep buying. Teenagers, inevitably, discover flavor (or cigarettes). What changes, as always, is who pays the price and who reaps the profit. And the question of prohibition, never answered, still hangs in the air: If the goal was protection, why was punishment the first tool reached for?