The Sound Health Makes as It Collapses

From the dream of universality to the collapse of cooperation. From international solidarity to the commodification of care and programmed dependency. What remains of health as a global common good?

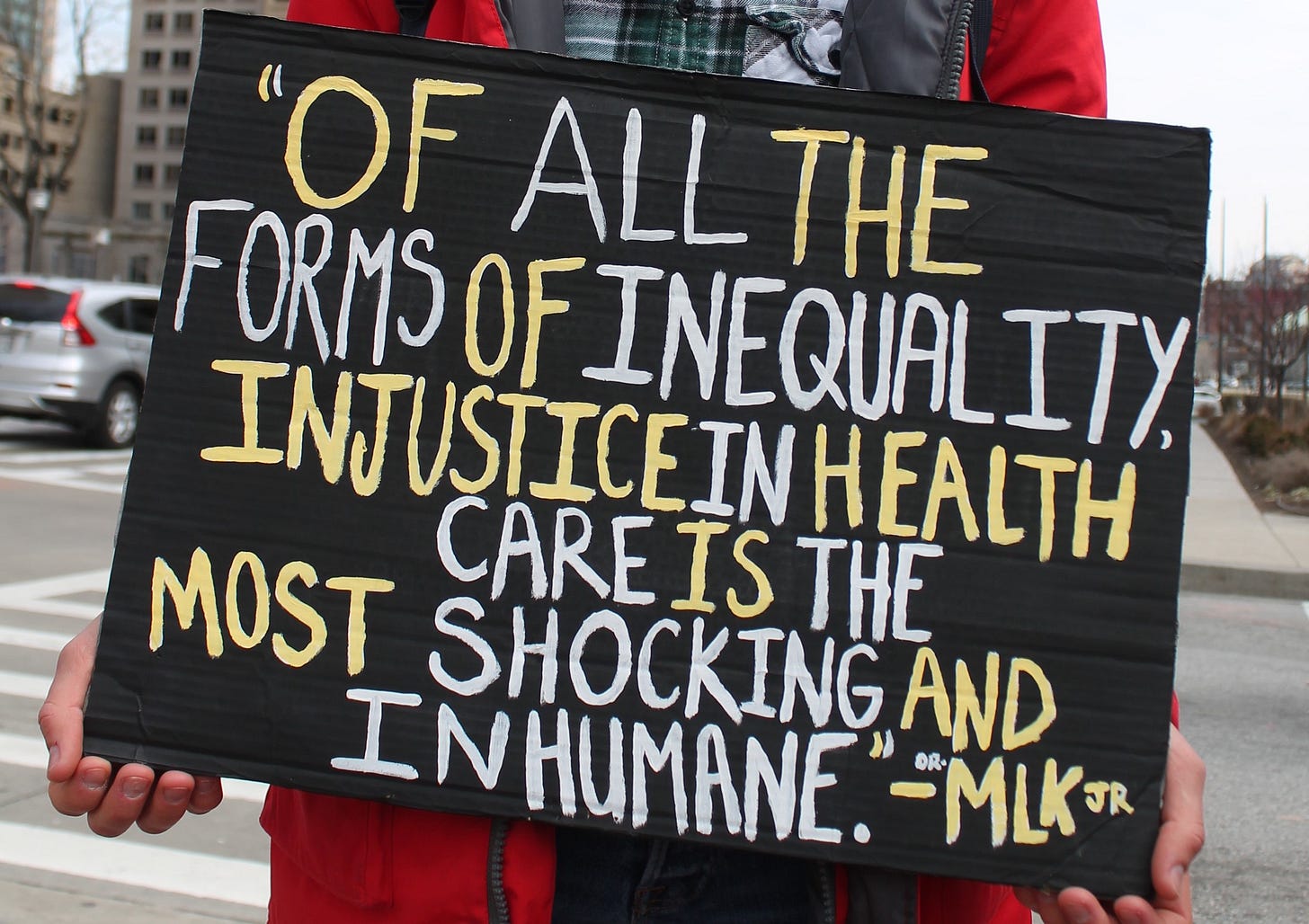

"Health is the cruelest mirror of political choices."

So often invoked by the Brazilian public health physician and highbrow Jairnilson Paim in foundational writings and lectures on collective health, this sentence now echoes with a near-unbearable urgency.

Cruel, because it is no metaphor, but a matter of fact. Every curve traced on an epidemiological graph hides faces, names, and lives abruptly cut short. And every budgetary decision, however technical it claims to be, is first and foremost a political act of mindset, desire, and will—an incision that bleeds through the bodies of society’s most vulnerable.

The coldness of numbers masks the violence of institutional neglect. It is in that abyss, between data and human drama, that the failure—or commitment—of a state is laid bare, without anesthetic. Because health, after all, is not just a government sector: it is the ethical thermometer of a society.

In the post-2020 world, the time between a viral outbreak in a remote sub-Saharan village and a diplomatic crisis in Brussels is no longer measured in borders, but in hours. Health, once the technical domain of discreet ministers and lab-coated experts, has moved to the center of global political and economic arenas. It has become an ideological battlefield, a cog in billion-dollar deals, a strategic tool in state diplomacy—reshaped and subordinated to the imperatives of profit and competition.

In international forums and scholarly journals, when experts warn of the “end of the golden age of global health,” they speak of more than shrinking budgets. What’s collapsing is an implicit pact—a moral and geopolitical agreement that, for three decades, upheld the survival of millions.

What is crumbling, in truth, is not just a funding model. It is the very idea of solidarity as a viable foundation for global public health.

Between Ruins and Promises

In a remarkable essay published in the Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health, Derek Yach, Aviva Ron, and Dorit Nitzan offer neither a technical brief nor a routine diagnosis. What they write, in plain and deliberate terms, is an obituary. And like any obituary that refuses the coldness of finality, it holds more than mourning: it carries an effort to map what might still be salvaged from the wreckage.

The trio argues that global health, as it was conceived in the 1990s—under the banner of interdependence and multilateral financing—has reached a historical turning point. What’s at stake now is not merely the allocation of resources, but something rarer, more fragile, and profoundly political: the ability to imagine new ways of caring, governing, and collectively negotiating life itself. Without that imagination, they warn, the future of global health risks becoming little more than a gentler repetition of its failed past.

To grasp the roots of today’s crisis, we must look beyond charts and balance sheets, towards what was once imagined, in a time before money became the measure of all things.

The Foundations Before the Collapse

Before it was subsumed by market imperatives and geopolitical power games, global health was, at least in part, envisioned as a civilizational project. A promise that no life should be abandoned to death for want of access, place, or passport.

To reclaim this foundation is not an act of nostalgia. It is to recognize that, beneath the ruins of failed systems, still pulses the idea of a world sustained by an ethical pact and a radical solidarity.

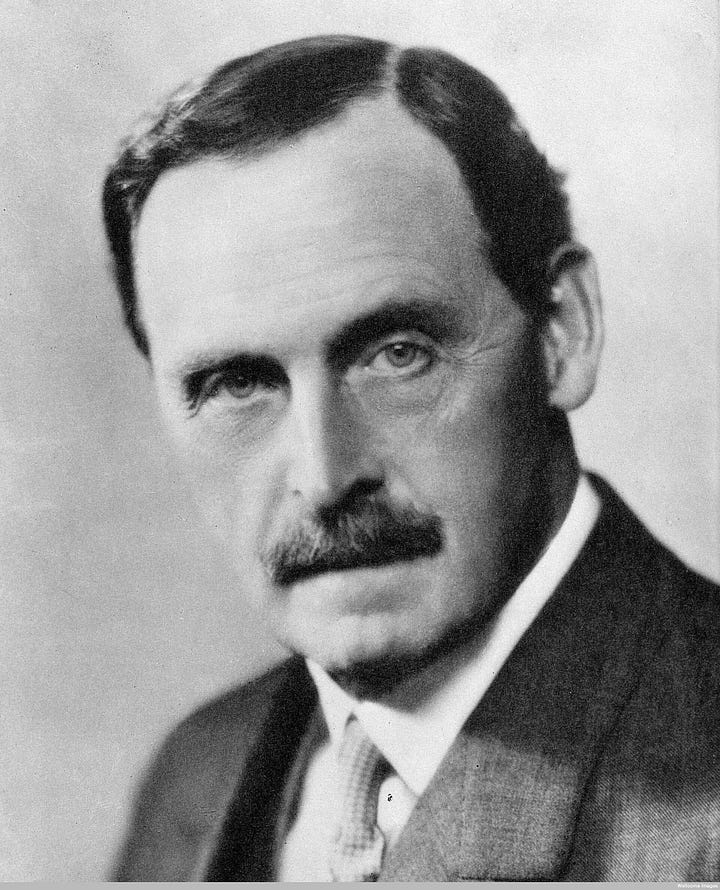

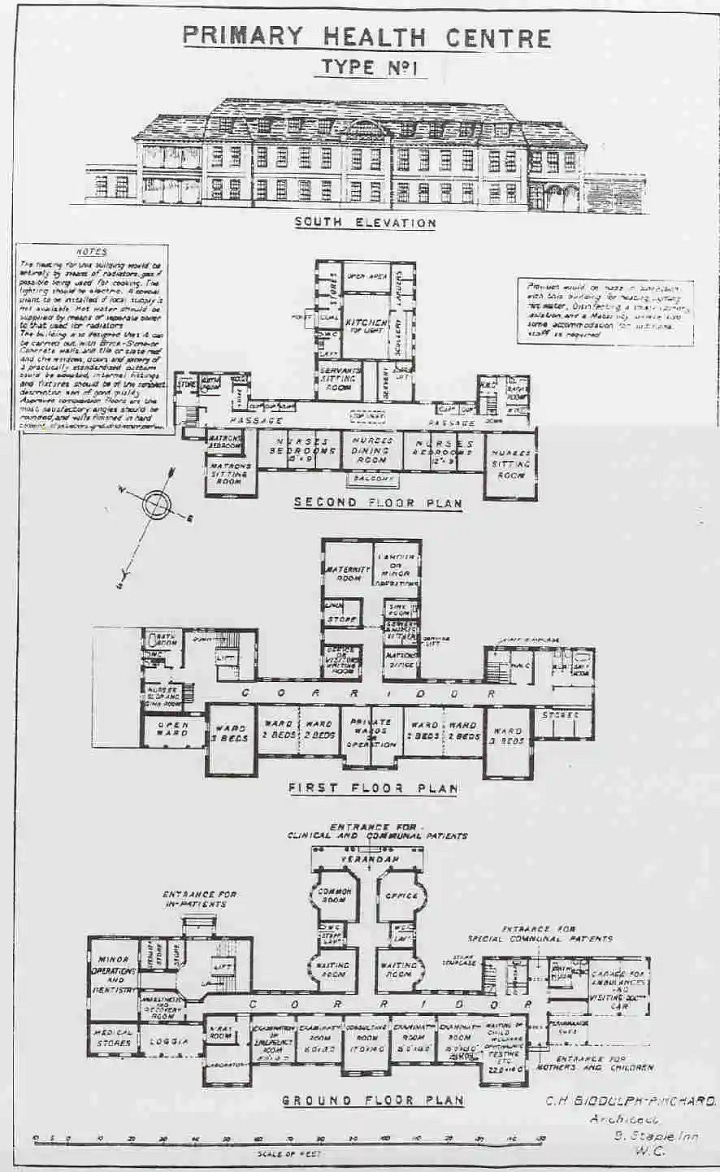

In 1920, in the aftermath of World War I’s seismic shock, the English physician Lord Bertrand Dawson presented a bold proposal to the British Parliament: integrated and decentralized health networks, rooted in communities—a system grounded in prevention, territorial care, and collective responsibility.

At the same time, in the nascent Soviet Union, the Semashko model was taking shape: the world’s first universal, free, and state-funded public health system. Grounded in collective rather than commercial principles, it combined strong state control with an emphasis on prevention and popular participation, centralizing services while organizing care as a social right.

Decades later, several elements of the Soviet model — universal coverage, an emphasis on prevention and public health, the structuring of care into levels, the centrality of primary care, and the promotion of hygiene — would shape health systems across the world. Among them, the United Kingdom’s National Health Service (NHS), established in 1948, stood out as the product of two key inspirations: the Dawson Report and the progressive, social-democratic vision embodied in the Beveridge Report. This legacy would resonate decades later in Brazil’s Unified Health System (SUS), created in 1988.

Dawson, for his part, anticipated ideas strikingly ahead of his time. He called for the creation of multidisciplinary teams to confront tuberculosis, mental illness, and other social vulnerabilities. With uncommon clarity, he envisioned what we now describe as integrated care and psychosocial support. His report — nothing short of visionary — already cast health as a right, not a privilege to be bartered under the rules of the market.

But the project was soon consumed by internal political disputes and by the conservative restoration that followed the war. Even so, it left an enduring imprint on future debates—a persistent trace of what might have inaugurated an entirely different paradigm: one in which care obeyed not the logic of profit, but that of proximity, and of human dignity.

Decades later, in 1959, the Cuban Revolution built—on the ruins of a profoundly unequal country and under relentless external siege—a universal, free, and territorially grounded health system forged in its own image: It was centered on prevention and public health, and sustained by participatory governance through local councils, associations, and mechanisms of social oversight at every administrative level. From the outset, it wove health initiatives together with basic sanitation and environmental preservation.

Cuban family medicine did not merely survive: it withstood economic blockades, the collapse of the Soviet Union, and chronic shortages of essential materials. It endured where so many other systems failed. And it endures still, under blockades that remain in place to this day. In doing so, it became an uncomfortable beacon on the global stage—living proof that a small island nation, with scarce resources but unwavering political will, could transform health into an instrument of sovereignty and collective dignity.

A symbolic affront to a Global North that still insists on reducing health to a commodity.

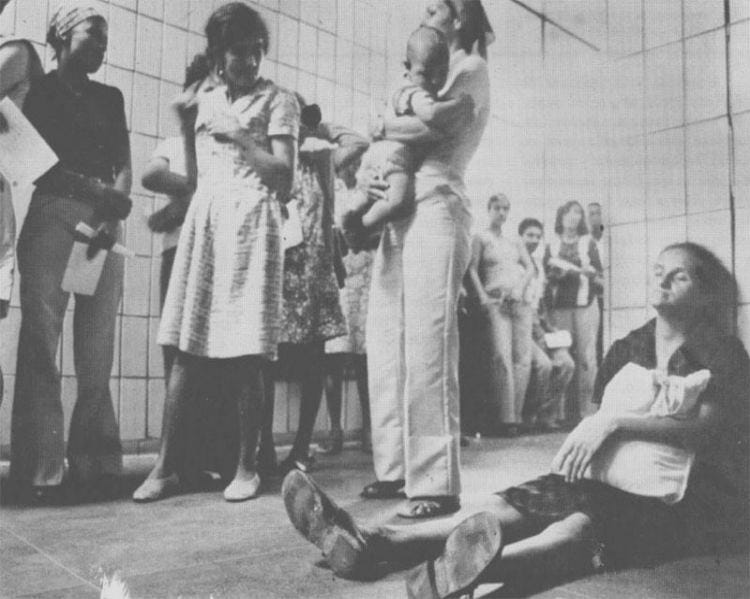

Around the same time, between the 1950s and 1970s, seeds of community health were quietly germinating far from the centers of power in African villages, Latin American forests, and small Asian hamlets. Many of these initiatives were missionary-led, some religious philanthropic; most improvised, sustained by scarce resources and the sheer urgency of care. Yet they shared something vital: a direct bond with the people. Practices rooted in listening and presence, in radical proximity where medical knowledge is intertwined with ancestral wisdom, emotional ties, and the rhythms of the land.

These projects were rarely formalized or praised in official reports, dismissed as marginal or anecdotal within dominant narratives. Yet they left traces—seeds of a different vision of health, one born from the ground, not from offices; from lived realities, not bureaucratic abstractions.

Examples include China’s “barefoot doctors,” as well as rural health worker schemes developed in Bangladesh, Guatemala, India, Mexico, Nicaragua, the Philippines, and South Africa. In Latin America, community-based health projects also flourished, many of them inspired by Paulo Freire’s pedagogical approach, reimagined and adapted to health education.

In the Southern Cone of the Americas, under Brazil’s military dictatorship, something profoundly subversive began to take root. It was 1976, and the newly created Department of Social Medicine at the Federal University of Pelotas dared to propose the unthinkable: a public health system that was free, universal, basic, and embedded in territories long abandoned by the state. At a time when repression tortured and disappeared people, silenced voices, and extinguished rights, to imagine health as collective emancipation was not merely an academic gesture; it was a political act.

Two years later, this local utopia, conceived in the midst of authoritarianism, would resonate on an international stage, proof that even under the heaviest shadows, it is still possible to plant the seeds of another world.

Alma-Ata: A Dream Interrupted

Kazakhstan, 1978. In the shadow of the Cold War, delegates from more than 130 countries—rich and poor, allies and adversaries—gathered in Alma-Ata, summoned by the World Health Organization and UNICEF. For a few brief days, the impossible seemed within reach.

The final Declaration was no mere technical report but an ethical manifesto: health affirmed as an inalienable human right, and primary care proclaimed as the universal path to achieve it. At the heart of the document, certain words pulsed like a secular—almost mystical—promise: Health for all by the year 2000. It was more than a target; it was a collective act of faith, a universal call to justice in health.

For a fleeting moment, the world seemed ready to forge a pact around life, not profit. But the geopolitical winds turned swiftly. The dream did not survive the market’s siege.

In 1980, just two years after the Alma-Ata Declaration, UNICEF itself, now allied with the World Bank, the Rockefeller Foundation, the Ford Foundation, and USAID, endorsed a strategic pivot: selective primary care, encapsulated in the acronym GOBI. Four interventions —Growth monitoring, Oral rehydration, Breastfeeding, and Immunization— were identified as the core of this new model. It was simple, cheap, and technocratic. A vertical response, ruled by numerical goals and the urgency of results.

This shift marked a rupture with Alma-Ata’s original vision of primary health care: comprehensive, universal, free, and affirmed as a human right. In its place arose a selective, technocratic, and increasingly commercial approach, promoted throughout the 1980s by multilateral agencies under the banner of neoliberal reform. Conditional funding and targeted interventions displaced the broad, participatory model envisioned in 1978. Narrow preventive measures were privileged over a holistic view of health as socially determined, corroding both the universality and integrative strength of health systems. At the same time, the rhetoric of efficiency, cost reduction, and privatization became the new orthodoxy shaping health policies worldwide.

It saved millions of children, true. But it also fractured health systems, dissolved the ideal of comprehensive care, and reduced healing to a checklist of procedures, privileging individual treatments over collective responsibility. As David Tejada de Rivero, then a WHO official, would later warn, the haste of certain international agencies—both within the UN and in the private sector—to demonstrate immediate results distorted the original concept of primary health care, when the goal should have been to foster lasting structural change. The logic of efficiency triumphed over the promise of a civilizational pact. And what was lost was the horizon itself: health as a right, not a patchwork of bandages laid over a wounded body.

In the Global South, a Constitutional Utopia

In the first years of democratic opening, after more than two decades of civil-military dictatorship, Brazil breathed—for a brief yet fertile moment—an air of civilizational renewal. Against the neoliberal tide reshaping the world, Brazil enshrined in 1988 a rare and audacious constitutional utopia: health as the right of all and the inalienable duty of the state.

Thus was born the Unified Health System—Sistema Único de Saúde, or SUS—conceived as a universal, free, and comprehensive project, open to every human being, woven into the fabric of daily life and rooted in the territories where people live. Yet this utopia emerged already under siege, as the same neoliberal forces dismantling public systems elsewhere were pressing at Brazil’s gates.

It was not merely a public policy. It was an intellectual, political, and ethical act of resistance against the global consensus of targeted, selective care. While much of the world was tuning its discourse to the logic of scarcity, Brazil inscribed into its Constitution a principle both radical and universal: no life—regardless of citizenship or place of birth—can be measured by its ability to pay. SUS emerged as a radical affirmation of equality: not only a national project, but a project of humanity itself.

And the Shine of Gold Is Fleeting

In the 1990s, health reappeared on the radar of global powers—not as a right, but as an opportunity. The World Bank began to reframe it as an economic asset: healthy bodies were now valued for driving growth, reducing risk, and boosting productivity. In the United States, the Institute of Medicine elevated health to a matter of national security, arguing that population health shaped workforce readiness, military capacity, and economic stability. Health thus acquired a strategic dimension that transcended humanitarian concerns. What had once been treated as a duty of care was rebranded as a geopolitical tool.

Between 1998 and 2003, Norwegian physician and former Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland took the helm of the WHO with an ambitious goal: to restore the organization’s central role on the global stage. To this end, she created the Commission on Macroeconomics and Health, chaired by Jeffrey Sachs, which in 2001 released a report framing health as a driver of economic growth in poor countries and outlining priority interventions. While influential, this reframing reinforced an instrumental logic: health was to be valued not as a right in itself, but as a means to productivity and competitiveness.

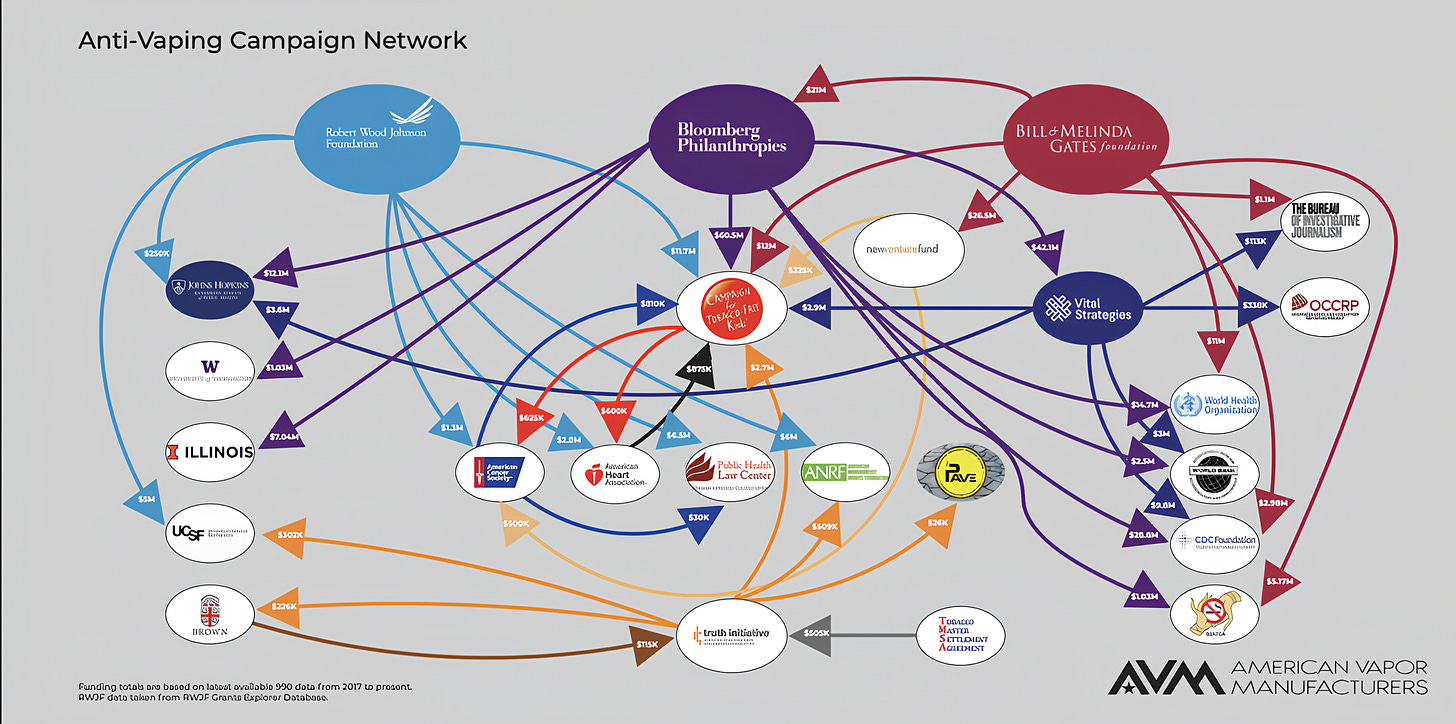

Determined to secure resources, Brundtland promoted global partnerships and international funds, bringing together governments, multilateral agencies, and private actors. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation quickly rose as a central player, channeling more than US$1.7 billion into immunization programs between 1998 and 2000. Within only a few years, nearly seventy new global health partnerships had been established, a transformation that repositioned global health within the circuitry of philanthrocapitalism.

The model, however, was far from consensual. Critics warned that alliances with the private sector risked eroding the WHO’s mission, fragmenting global health governance, and channeling resources toward a narrow set of diseases at the expense of strengthening health systems as a whole.

Yet Brundtland’s leadership also restored visibility and centrality to national health systems, underscoring effectiveness, equity, and responsiveness, as emphasized in the 2000 World Health Report. She placed the reduction of health inequalities at the core of her agenda, with a focus on lowering mortality and morbidity among impoverished and marginalized populations, while promoting healthier lifestyles. Under her tenure, maternal and child health, vaccination, nutrition, mental health, and the fight against both communicable diseases—such as malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS—and chronic conditions like cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease regained prominence on the global stage.

For a brief moment, health dared to speak the language of power. But the gold was thin, and the window short. In this climate of strategic euphoria were born Gavi, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, and PEPFAR—the U.S. global HIV initiative. International health funding soared: from $5.6 billion in 1990 to more than $40 billion by 2020. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation poured in unprecedented sums, reshaping the field through the lens of corporate philanthropy and measurable efficiency. Diseases once relegated to the margins—HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria—now occupy center stage.

It was, without doubt, the so-called golden age of global health: an improbable fusion of private capital, public diplomacy, and epidemiological emergency. Yet beneath the gleam, a new dependency was taking root—health systems weakened and reorganized around a handful of diseases, increasingly exposed to the shifting priorities of funders.

High-impact campaigns saved lives, yes—but they operated as islands of excellence in oceans of fragility. Lacking integration into national systems and dialogue with local realities, these efforts turned into temporary, almost illusory solutions, unable to build lasting networks of care. As private economic interests advanced, they curtailed the very possibility of consolidating a broader paradigm of health—one rooted in social, territorial, and integrative dimensions.

Health in the Age of Philanthrocapitalism: Campaigns, Capital, and Dependency

Starting in the 2000s, as global health became more intensely globalized, private and corporate actors—such as the Gates and Bloomberg foundations, pharmaceutical conglomerates, and multilateral financial institutions—moved to the center of priority-setting and method design. Their influence expanded across every front: political, technical, and financial. They did not merely fund projects; they reconfigured agendas and redefined what counted as success. They brought capital, yes, but also algorithms of efficiency, impact metrics, and governance models insulated from democratic oversight. Beneath the varnish of philanthropy, a new paradigm took hold: health recast as investment, life as a risk-bearing asset.

It was within this landscape that the Gates Foundation emerged as the emblematic case. With its multibillion-dollar endowment, it became not merely a donor but a power broker, shaping global health priorities in ways that rivaled—and at times eclipsed—traditional multilateral institutions such as the WHO. Vaccines, drugs, and technological fixes became its hallmark, driving quick wins against high-profile diseases like polio, HIV, and malaria. Yet this focus on targeted interventions often came at the expense of long-term investments in health systems, infrastructure, and workforce—less visible, less glamorous, but indispensable for sustainable progress.

Critics argued that this narrow focus crowded out attention to other urgent crises: chronic diseases, mental health, malnutrition—burdens that fall heaviest on low- and middle-income countries. Others questioned the very model of philanthrocapitalism, in which the logics of markets and management science seeped into the governance of public health. The result was a system in which decisions shaping the lives of millions were increasingly steered by private actors—answerable not to citizens or parliaments, but to their own boards, metrics, and visions.

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the tensions crystallized. The Gates Foundation initially resisted calls to waive vaccine patents—a stance that, according to critics, hindered equitable access in the world’s poorest countries. The episode exposed a deeper dilemma: in the absence of strong global institutions capable of regulating wealth and power, must humanity resign itself to a future in which the fate of global health rests in the hands of a few private fortunes?

This new governance imposed a logic anchored in economic growth, the expansion of health markets, and the proliferation of specific technologies—often at the expense of social determinants, equity, and the structural transformation of living conditions. In this landscape, the World Health Organization grew increasingly dependent on donations tied to private interests. That dependency eroded its institutional autonomy and redirected its focus: away from building universal public policies, toward implementing strategies molded by commercial imperatives.

For the Global South, this translated into a new conditionality: countries received pre-packaged interventions, centered on narrow targets and disconnected from the complex realities of their health systems and the social fabric that sustains them. Behind the humanitarian rhetoric, health was increasingly managed like an investment portfolio—broken down into indicators, packaged into replicable models, governed by return-on-investment logic.

The result was a structurally fragmented landscape, incapable of sustaining permanent care networks. What it produced were zones of intervention, not systems. Results, but not justice. And what gleamed in international reports—in shimmering charts and statistics—often masked a deeper absence: that of integral, universal, and sustainable systems capable of caring beyond the emergency.

Exhaustion Before the Fall

In 2010, the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) marked the peak: global health financing flows reached their highest level. Yet even at the summit, signs of exhaustion were already clear. Funding began to plateau. Institutional fatigue was unmistakable. As if the model had hit not only its expansionary limit, but its imaginative one as well.

Still, in 2015, the UN launched the Sustainable Development Goals, with a target date of 2030, emphatically reasserting the promise of universal health coverage. The contrast was glaring: a bold new horizon proclaimed just as the foundations were beginning to crack. It was the final glimmer of a fatigued utopia—more performance than possibility, more spectacle than substance.

Five years later, the COVID-19 pandemic laid bare what had long been fracturing. It exposed rifts long buried under decades of rhetoric, fragile agreements, and well-packaged palliatives. In 2021, emergency health funding surged to $70 billion—ventilators were transported across oceans on military planes, labs mobilized global task forces, and governments declared states of emergency and exception. Yet behind this logistical choreography, another reality was quietly taking shape: the relentless accumulation of debt. While lives were saved with wartime urgency, the future of entire countries was mortgaged. The pandemic didn’t just kill—it reconfigured the terms of global dependency. It left visible scars in graveyards, and invisible ones in the balance sheets of generations yet to come.

By 2021, contraction was no longer a trend—it was a settled fact. The United Kingdom, once a pillar of global health funding, slashed its international aid. The United States, under the Trump administration, froze billions in transfers, suspending PEPFAR—the very program that for two decades had symbolized its commitment to fighting HIV in the Global South. Europe, fractured by regional wars, inflation, and internal instability, redirected resources inward. The World Health Organization, in turn, announced a historic deficit.

But this wasn’t merely a financial crisis. What was beginning to collapse was the entire edifice of multilateral global health—its pacts, its promises, its legitimacy.

An uncomfortable silence replaced cooperation. And where once stood an architecture, only diplomatic rubble remained.

Who Decides What It Means to Protect Life?

In the essay by Yach, Ron, and Nitzan, the collapse of global health is portrayed as more than fiscal—it is symbolic. They describe a dual breakdown: not only the failure of international financing mechanisms, but also the erosion of the collective imagination that once sustained the idea of multilateral cooperation rooted in equity.

As major donors retreat, regional coalitions are beginning to step into the void. The Africa CDC stands out as a sign of autonomy in the making—an attempt to rebuild a coordinated, rooted response from within the continent itself.

Meanwhile, China advances with its Health Silk Road, offering large-scale packages of funding, hospital infrastructure, and biomedical technologies—marked by fewer political conditions and a tighter strategic centralization.

What is emerging is not merely a competition over trade routes or diplomatic influence. It is a struggle for the very grammar of care on a planetary scale. And the question, quietly haunting the corridors of power, is this: Who will decide, from now on—and in the near future—what it means to protect life?

Battling the Programmed Suffocation of Public Health Systems

Meanwhile, countries such as Brazil, Mexico, and India wage a daily, and often solitary, battle to sustain their public health systems. They confront chronic underfunding as a form of slow suffocation; the steady capture by private interests, which turn care into a commodity; and cultural resistances carefully cultivated over time, from the manufacture of misinformation to the systematic teaching of contempt for universal public policies.

In many cases, the threat comes not only from outside: it resides deep within the institutional machinery itself. Private health plans, hospitals, pharmaceutical industries, and medical equipment manufacturers operate with strategic intensity to bend public policy, legislation, and regulation to their advantage. They wield technical expertise, cultivate cross-party alliances, and maintain direct access to both executive and legislative branches—shaping decisions in their own image. Decisions that often rest on the deliberate weakening of the public system.

In Brazil, for example, these sectors lobby for deregulation of the private insurance market, bankroll repeated attempts to fragment the SUS, and interfere directly in primary care policy. Under the rhetoric of “relieving” the state, they promote the expansion of private markets that, in practice, drain public resources, entrench inequalities, and hollow out the very foundations of the public system. What is presented as complementarity is, in fact, a slow-motion dismantling: a strategy of privatization by attrition, eroding the constitutional promise of universal health.

There are recurrent allegations of illegal campaign donations, opaque alliances between political representatives and health industry executives, and systematic efforts to weaken the regulatory authority of government agencies. This is not merely a fight over budgets—it is the silent erosion of a public covenant, the dismantling of a societal project.

Brazil’s public health system illustrates both the scale and the stakes: it currently holds some 340 million active records, surpassing the country’s population due to duplicate entries, deceased individuals, and its universal coverage, which also extends to foreign patients.

In India, the fragmentation of the health system takes even starker forms. The private sector dominates, absorbing nearly 70% of direct health spending, often through low-quality services delivered under minimal regulation. Its influence extends deeply into public policy, steering decisions that expand markets while further hollowing out an already weakened state system.

The growing outsourcing of public functions to NGOs and private entities—often financed by foreign donors—undermines care integration and erodes the State’s health sovereignty. Innovation, meanwhile, runs into institutional barriers, fragmented coordination among actors, and structurally unequal competition with powerful transnational corporations that shape priorities and drain resources. Even programs such as the National Rural Health Mission have been unable to reverse the pattern: deep social and territorial inequalities persist, aggravated by the low political mobilization of the very populations most affected.

In contrast to this logic of commodification, alternative forms of resistance continue to surface—such as the People’s Polyclinics, which uphold a model of universal, territorial, and solidarity-based access. Yet they survive only at the margins, almost underground, crushed beneath the weight of privatist hegemony. Scattered and fragile, they are beacons in the fog of a system already captured.

Mexico, too, lives with a deeply segmented health system—an intricate weave of public and private subsystems, fractured by sharp regional, social, and institutional inequalities. The private sector exerts growing influence, pressing for deregulation, privileged access to public funds, and the expansion of insurance schemes and services designed for the economically advantaged.

This dynamic undermines the pursuit of universalization, deepens the segmentation of care, and consolidates public–private partnerships that do not necessarily expand access, and often distort it. As a result, the most vulnerable remain underserved, forced to shoulder high out-of-pocket costs: a regressive model that privatizes risk and transfers the burden of health onto the individual.

Mexico’s challenge is twofold: to strengthen a truly universal public system, and to forge regulatory frameworks robust enough to resist capture by private interests, without succumbing to technocracy or clientelism. Ultimately, the task is nothing less than to return health to the realm of rights, and to wrest it away from the logic of privilege.

In these contexts, the legacy of Alma-Ata survives more as principle than as practice: preserved in official drafts, echoed in academic papers, invoked in conference speeches, lingering at the margins of ministerial guidelines. Yet in daily life, it is eclipsed by quick, technological, and profitable fixes—solutions that parade as innovation but, in practice, often deepen exclusion.

The promise of territorial, comprehensive, and universal care has faded into the background noise in a global system that has ceased to listen.

And yet, it is precisely this promise that many still cling to, not out of nostalgia, but as a horizon. Because even among ruins, some principles refuse to die.

In the hallways of a health post in Fortaleza, in the crowded alleys of Kolkata, in the rugged hills of rural Puebla, doctors, community health workers, nurses, and patients keep sketching, through small, daily gestures, the underground continuities of Alma-Ata. No longer a grand international pact, but a radical, quiet practice: one that, by refusing to abandon a life because it is poor, peripheral, or invisible, reaffirms health as a non-negotiable right—and as the possible language of another world.

Is There Still Time?

The proposal by Yach, Ron, and Nitzan is, at its core, pragmatic: diversify funding sources, strengthen regional coalitions, and reinvent the institutional architecture of global health. It is not a call to return to the past, but an attempt to sketch a new possible pact—less hostage to volatile donors, more anchored in durable political solidarities.

But how can one do that in a world where the very notion of the international common good seems to be disintegrating in real time, where cooperation yields to competition, science is weaponized as an ideological and diplomatic tool, and care is converted into a geostrategic asset?

The question, then, is no longer whether there is still time, but what there is still time for. To restore what has been lost? Or to imagine, at last, what was never allowed to be born?

Perhaps the future of global health no longer lies in conferences, billion-dollar funds, or fragile pacts between unstable states and private interests. Perhaps it lies quietly in the hands and voices of those who go on caring, even when everything around them has already surrendered.

There are promises that outlive their own betrayal. And there are ideas—such as the belief that every life matters—that persist, even when the world pretends not to hear.

The absence of solutions is not neutral: it has measurable, devastating costs. The freezing of PEPFAR alone, if sustained, could lead to as many as 500,000 additional child deaths from AIDS by 2030. These are not abstract projections. They are interrupted futures: children condemned by decisions made behind closed doors, far from the communities affected, far from real bodies, real lives.

Decades of research, public investment, and international scientific cooperation now hang in the balance—not collapsing with a bang, but with the slow, implacable silence of sand slipping through our fingers. What once appeared solid reveals its fragility. And what we believed secured shows itself, in the end, to be reversible.

Epilogue: A Deferred Promise

Global public health has known its visionaries. Lord Dawson, who imagined territorial networks when the world was still sifting through rubble. Fidel Castro, who turned medicine into an instrument of sovereignty. Halfdan Mahler, who gave the world Alma-Ata and its audacious call for health for all. Salvador Allende dreamed of universal health as a pillar of social justice. Amartya Sen, who argued that health is not a service but a freedom on which all others depend. And the anonymous ones—public health workers, activists, community organizers—who, in times of transition and fragile hope, dared to invent the SUS.

Global public health has also known promises that have gone unfulfilled: Alma-Ata, harm reduction, the Sustainable Development Goals, and the enduring dream of an integrated, just, and solidaristic system. However, what prevailed more often than not was abandonment. Not the explicit, declared kind, but the quiet one—seeping through budget cuts, buried in technical reports, detoured into diluted agendas.

An abandonment that does not collapse, but corrodes. That does not shout, but silences. That does not deny, but defers. A promise postponed so many times that it begins to take the shape of forgetting.

And yet every deferred promise carries within it—by definition—the possibility of return.

Perhaps the task now is not to repeat old projects, but to relearn how to imagine them—not out of nostalgia, but out of persistence. Because, in truth, we have yet to find a more dignified way to care for one another.

“Health for all by the year 2000,” Alma-Ata once promised. We arrive at 2025 with a painful reversal of the question: how many still have health as a right—and not a privilege?

If the so-called golden age is over, perhaps the real question was never about its ending, but about its existence. Why did health have to be golden in order to be universal? And how do we imagine a future in which access to life does not depend on extraordinary financial flows, but on the hardest—and least spectacular—of political choices: the ethical commitment to care as principle, not as exception?

Claudio, excellent post, it identifies the profound crisis of "global" health. However, your description of the Mexican case is very inaccurate. Private agents are not the main culprits of the malfunction of public health services. Rather, the governmental health sector was literally dismantled by terribly misguided and erratic state interventions personalized by the previous president Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), who had a vertical iron power over all issues during its presidency.

Obviously, the health sector before AMLO was far from functional (as you mention), but previous administrations made an ongoing effort to palliate deficiencies, to coordinate and regulate the subsystems, to rationally expand coverage and improve quality. The nucleus of the effort was the "Seguro Popular", reaching tens of millions of families, reaching agreements with private sector providers of services and medication. It was far from reaching Scandinavian efficiency, but it moved.

Unfortunately, AMLO cancelled it as soon as he was elected in 2018, allegedly because of "corruption acts" that was never proved (no demands against officials), it was just AMLO's banging on the table to show "who is the boss here", a constant attitude of this autocrat in many other issues. The Seguro Popular was replaced by a white elephant (INSABI) that collapsed in 2022. Since then there is a serious crisis of medication supply, generated by the capricious and improvised disruption of the previous system.

AMLO channeled his authority on health issues to Dr Hugo López Gatell (one of his favorite proteges), a very incompetent and authoritarian technocrat. The consequences: handling of the COVID pandemic in Mexico was among the worse in the world: 400 hundred thousand "recognized" deaths (over 800 thousand real deaths considering demographic evidence). More than 70% of the Mexican population lack even minimal public health services, which forces lower income sectors to pay for lower quality private services. Public health services in Mexico are agonizing.

The current president, Claudia Sheinbaum, was hand picked by AMLO. Her health minister is a well known and competent MD, but they inherited AMLO's disaster and lack the autonomy and power to implement changes, since AMLO still wields too much power behind the throne (he appointed all the main officials, legislators, governors of the ruling party, so they owe loyalty to him, not to Sheinbaum),