The Rope and the Smoke

Binding Destinies or Weaving Survival: The Invisible Thread of Our Choice

Each year, we braid an invisible rope with our dead.

We know how to stop it, we know what to save—and yet, we choose to look away.

While millions remain trapped between smoke and indifference, the real question is neither technological nor held in the parched hands of the market: It is whether we will have the courage to stop condemning entire generations to die by habit.

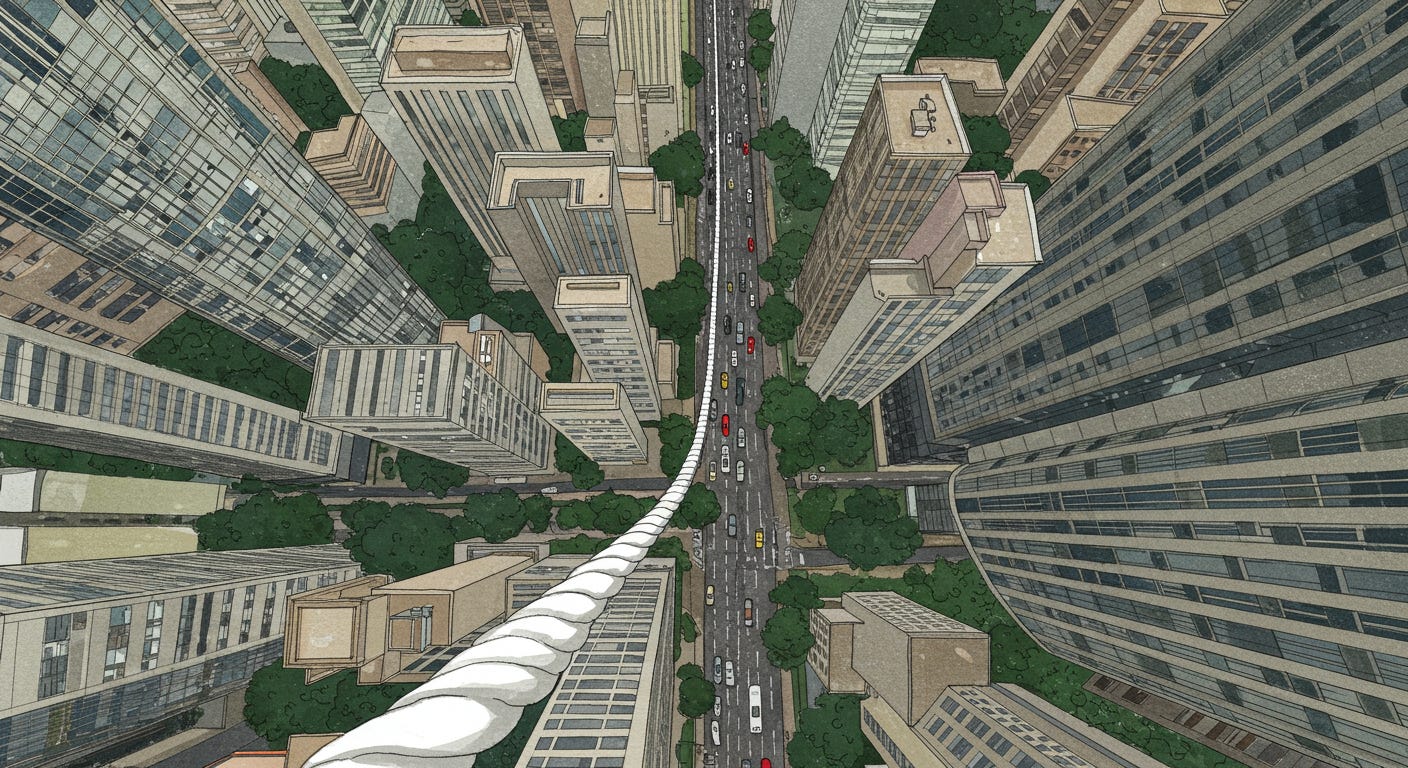

Imagine a white rope, unfurled like a taut sigh from the Plaza de Mayo in Buenos Aires, cutting through the thick, warm wind of Mexico City’s Zócalo, and snaking—like a river of mourning—between the skyscrapers of São Paulo’s Avenida Paulista. A rope nearly three kilometers long, where every millimeter condenses a life lost in Brazil, Mexico, and Argentina over the past year: a fragile fabric of absences not even the wind can unravel. To walk beside it would be to traverse a cemetery without graves, a terrain of absences meticulously mapped.

Each segment, demarcated with surgical precision: heart disease in vivid red, cancers in ashen gray, traffic accidents in brittle yellow. Further along, the widest stretch, dyed a dense and absolute black, would mark deaths caused by tobacco: 271,695 lives reduced to a few meters of frayed fiber. Every step would summon an absence: collapsed lungs, hardened arteries, hearts exhausted after years of inhaling smoke, as though breathing ash until dissolving into air.

Yet beyond that dark tide, another rope could stretch—brief, almost timid, like a distant thread of hope. Inspired by a distant model—the Swedish approach—this rope would tell another story.

In Sweden, where tobacco smoke has largely been replaced by smokeless nicotine, tobacco-related deaths are now the lowest in Europe.

Each year in Argentina, approximately 45,000 people die from smoking-related illnesses. In Mexico, 65,000. In Brazil, 161,695. If Brazil, Mexico, and Argentina adopted this approach, over 270,000 lives could be saved annually.

Now imagine an endless line of 270,000 bodies, shoulder to shoulder, stretching like a frozen human river across 135 kilometers—roughly 84 miles. A distance spanning Buenos Aires to Mar del Plata in Argentina, New York to Philadelphia in the U.S., Madrid to Toledo in Spain, or London to Cambridge in the U.K. A silent procession crossing fields, cities, and highways, carrying in its stillness the memory of a heartbeat that no longer exists.

This is not a battle over permitting or banning products: It is a struggle between life and death, between the time we still own and the time slipping irrevocably through our fingers. Between remaining in the line of the living or being forever fixed among those who will not return.

The Swedish Rope: A Lesson in Risk

This visual analogy is not new. It was conceived by Thomas Ericsson, a Swedish scientist and pioneer in tobacco harm reduction. In a recent New Yorker article by Carrie Battan—titled Lip Service (March 17 print edition)—Ericsson unfurled his metaphor: a 95-meter rope, where each millimeter embodied a life lost in Sweden in one year.

On that rope, markers trace a cartography of risk.

Smoking occupies one of the longest segments, like an open wound refusing to heal.

Alcohol, slightly shorter, lingers close behind. Suicides, traffic accidents, drownings: ever-smaller signs, like fading echoes.

Finally, at nearly invisible ends lie deaths from wasp stings or smokeless nicotine. His message was clear: The disproportionate fear of nicotine, absent combustion, brutally contrasts with its near-nonexistent real-world risk.

The Scale of Harm Is Brutally Evident

If we replicated Ericsson’s model in Latin America, meters would not suffice—we would need kilometers.

In Brazil, per DATASUS data, the rope would stretch roughly 1.5 kilometers: 400 meters for cardiovascular disease, 230 meters for cancer, and 161 meters for smoking-related deaths. In contrast, smokeless nicotine’s risk would occupy just 4 centimeters, or 0.0027% of total deaths.

In Mexico, the rope would span 848 meters: 200 meters for heart disease, 91.6 meters for cancer. Smoking would claim 76 meters, while smokeless nicotine would barely reach 2 centimeters, 0.0024% of deaths.

In Argentina, a 321.4-meter rope would fray into 99.5 meters of heart disease, 48 meters of cancer, and 45 meters tied to smoking. Smokeless nicotine’s imprint would not even span a centimeter—a speck against the vastness of preventable harm.

Beyond Numbers: Human Stories

Behind each meter of rope, pulses a name that no longer answers, a shattered family, a void that refuses closure.

To listen to patients marked by smoking in hospitals across Buenos Aires, São Paulo, or Mexico City is to glimpse a mosaic of loss: lungs surrendered, faces etched with premature wrinkles, broken promises floating in silence-choked rooms. Each story drags the echo of a goodbye that, when finally uttered, was already too late.

In contrast, Sweden’s strategy of replacing cigarettes with snus and other smokeless nicotine has drastically reduced tobacco-linked lung diseases and cancers. According to Health Diplomats data, Sweden now reports Europe’s lowest tobacco-related mortality rate.

This harm reduction approach challenges prohibitionist logic: It demands no absolute renunciation but proposes a more humane transition, offering alternatives that slash harm without condemning desire.

Thomas Ericsson: Architect of Silent Change

Thomas Ericsson is not just an innovator. He is a practical humanist. Trained at pharmaceutical giant LEO Pharma, he helped pioneer Nicorette nicotine gum in the 1980s—an early attempt to tame addiction without destroying the addict. Years later, alongside colleague Per-Gunnar Nilsson and his son Robert, he refined white snus: a clean reinvention of an ancient habit, designed to save lives without demanding impossible perfection.

His philosophy hinged on a simple premise: He sought not to sell medicine, but to offer something people would freely choose—something that didn’t make them feel diseased. After suffering a heart attack in 2022, Ericsson became his living experiment: avoiding pollution, daily aspirin, and using his smokeless nicotine product with moderation.

In his analogy, Ericsson does not downplay risk—he frames it proportionally. Dying from snus, he explains, is as improbable as death by wasp sting. Smoking, however, delivers a near-guaranteed sentence to millions.

Obstacles and Opportunities in Latin America

Why, then, have Brazil, Mexico, or Argentina not followed this path? What forces—visible and invisible—block strategies that could save tens of thousands yearly?

The answer tangles in a dense, sticky web: social prejudices spread like spores, media misinformation clouds judgment, pressure from traditional anti-tobacco groups fossilizes debates, and corporate interests reinforce regulatory barriers.

In this poisoned landscape, all nicotine is demonized, with no line drawn between smoke and its absence.

Meanwhile, the chance to save tens of thousands of lives each year slips silently away, trapped between institutional apathy and the weight of unquestioned prejudices.

A strategy shift, inspired by Sweden, could rescue an entire city each year: a Rosario, a Cancún, or a Porto Alegre pulled back from oblivion. This is not a market issue: It is, fundamentally, a question of humanity.

The Fate of the Rope

In the end, the image lingers: The rope could keep growing, coiling daily into new millimeters of preventable tragedy. Or it could begin to shorten—imperceptibly at first—saving one life here, another there, until slowly, it twists the destiny of entire generations.

The choice is not technical or ideological. It is profoundly human.

We are not debating a mere product. We are deciding what time we choose to inhabit, what lives we dare to preserve, and what future we dare to sow.