The Room Where the War Pauses

Radical Care vs. the Forever War: In Colombia, between syringe and state, a supervised room tests drug policy — and proves that care can outlive punishment.

The idea is simple. The politics aren’t. You walk in expecting policy; you meet people. Start with the mirrors: tilted to catch a breath before it fades. In central Bogotá, Cambie—South America’s first supervised consumption site—rehearses a slow, unfashionable politics: keeping people alive. Colombia is taking its case abroad and, as Jacqui Thornton reports in The Lancet, this experiment arrives with evidence, not promises.

First, there’s an unmarked door — discreet, almost invisible — as if asking the city for permission to exist. Then, a suspended silence: a bright room where the brutality of the street slowly dissolves into the smallest gestures — cotton swabs, clean mirrors, tiny cups of coffee steaming between trembling fingers. Here, time bends. Pain, if only for an instant, is disarmed — beneath the fragile varnish of routine — as delicate as it is necessary.

This is Santa Fé — Bogotá’s exposed underbelly. A neighborhood where graffiti doesn’t just cover walls: it argues with the law, taunts the state, insists on existing. Nearly a hundred thousand people live here, between business towers and street markets, sleek high-rises and collapsing colonial houses — a fragile heartbeat of culture echoing along the city’s forgotten edge.

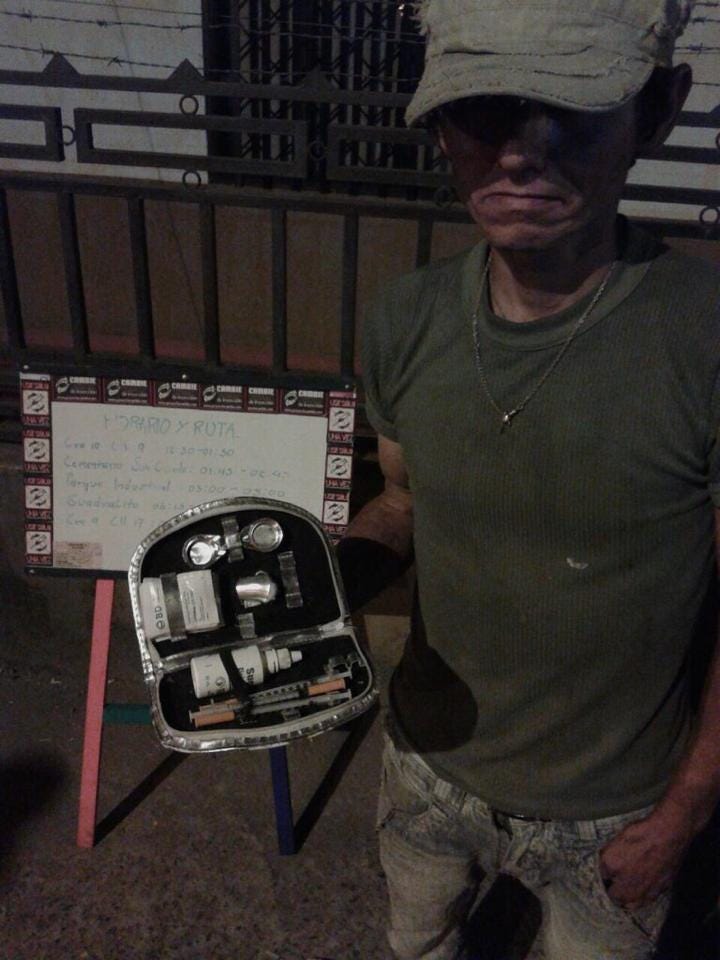

It is on this porous — and therefore fertile — ground that Project Cambie has taken root: South America’s first supervised drug consumption site. A place where drug use ceases to be a crime and becomes an encounter — where technique, care, and public policy inhale and exhale in the same space.

This is more than a local remedy. It marks a turning point in a country that, while still leading the world in coca cultivation, is beginning to chart a different course — choosing, instead of punishment, to experiment with the language of care.

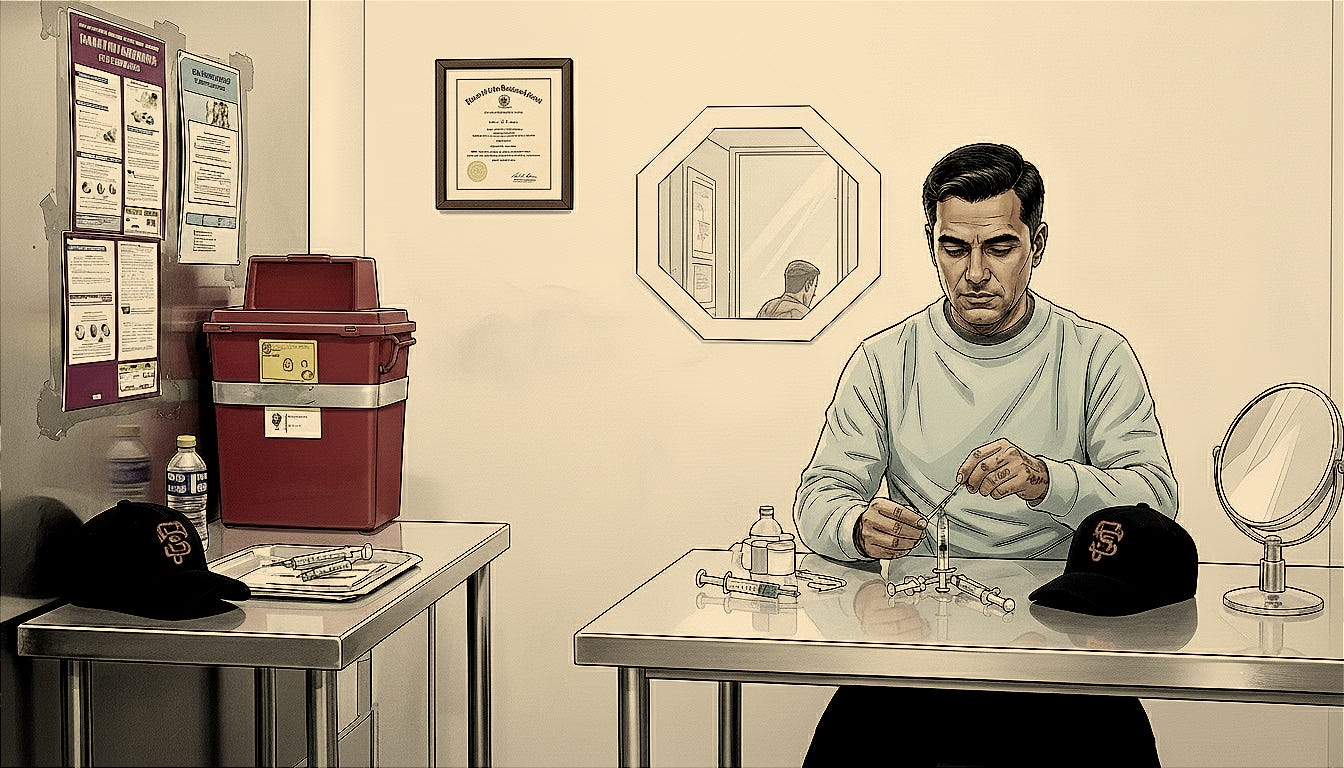

Inside Cambie, the language of care is not spoken — it is performed. It lives in the measured tone of the nurse who greets each visitor by name, in the calm choreography of gloves pulled tight, in the quiet that follows the metallic snap of a lighter. Every gesture here carries intent: to preserve life, to postpone death, to make time itself a little less cruel.

No one rushes.

The room breathes with its own rhythm — slow, deliberate, almost defiant. A man nods off at the counter; a social worker adjusts his chair so he won’t fall. Another asks for coffee, then forgets he asked. The volunteers do not correct him. They listen, they wait, they hold space.

It is at this intersection — between sterilized syringes and UN resolutions — that Jacqui Thornton’s Harm Reduction in Colombia finds its footing, illuminating a Latin American dilemma with global resonance.

The World Report, published in The Lancet on May 17, 2025, traces both the advances and the frictions of Colombia’s harm-reduction-driven drug policy, taking Bogotá’s Project Cambie as its case study. With clinical precision, it weaves the local scene into the fabric of international politics — and into the hard limits of a domestic budget stretched thin.

Thornton advances two ideas — simple in form, pivotal in consequence.

First: Colombia has opened an unprecedented window for rights-based drug services.

Second: that window could close if implementation and funding fail to keep pace with rhetoric.

She frames this tension around a question as direct as it is uncomfortable: What does it really mean to prioritize harm reduction?

Let’s start with what can be seen.

At Cambie, people bring their own drugs. They’re guided through testing — including checks for traces of fentanyl — before injecting themselves in small booths equipped with two mirrors: a large one in front, allowing staff to watch for the slow signs of overdose; and a smaller, magnified one, used by those who must find a vein in the neck or the forehead.

The details are clinical, but the intent is political: to reduce deaths in a place where risk has been accumulating for decades.

At Cambie, there’s peer support, a technical team, and basic care — wound treatment, counselling, coffee, and nearby showers.

For the program’s coordinators — psychologist Daniel Rojas Estupiñán and nurse Betty García — the task is to guide safe use, never to inject.

They’re also the ones who intervene when the worst happens: with intramuscular naloxone on site, and a nasal version used during weekly street outreach — when the team also collects discarded syringes scattered across the neighborhood.

It’s a pragmatic design, almost handmade. Here, half of the users have survived at least one overdose; nearly as many have endured three or four. So when Rojas says the focus is safety, care, and education, it isn’t rhetoric. He explains that their work isn’t transactional — that what drives them is simple: people matter to them.

Then come the numbers — what they reveal, and what they leave unsaid.

In its first year of operation, Acción Técnica Social (ATS), the organization behind Cambie, recorded 1,564 visits by 67 individuals. Fourteen overdoses were reversed — ten inside the facility, four in the surrounding streets. The last severe case was in April 2024.

These are rare metrics in a statistical landscape full of holes.

In 2022, official studies recorded zero cases of heroin use in Bogotá — even as a parallel estimate suggested that 2,841 people were injecting drugs in the capital. National data from 2019 estimated that 0.02% of Colombians used heroin — roughly 3,600 people — and 0.6% used cocaine, or about 136,000. Numbers that, taken together, say less about consumption than about what the country chooses — or fails — to count.

In other words: the places where measurement matters most are precisely where it’s done worst. And yet, the reversal of fourteen overdoses is an unambiguous fact — something that exists beyond the margin of error, beyond undercount, beyond doubt.

But the operation falters at a point that appears technical — and for that very reason exposes itself as a political decision in its purest form. In the event of an overdose, Cambie’s team faces a critical constraint: they cannot reliably administer oxygen. Colombian Ministry of Health guidelines restrict its use to formally authorized medical facilities, effectively excluding community-based spaces like Cambie.

The contradiction is stark: although oxygen is recognized as an essential intervention in overdose management, the service cannot fully provide it — it doesn’t fit within the conventional categories of the health system.

Once again, the rulebook denies the urgency of life.

So Cambie turns to the ambu bag, a manual fix for a reality that no longer fits the manual.

Under eighteen? They’re not allowed in.

What’s said here is what the city center refuses to hear: it’s the young who face the highest risks, who endure the most harm — and yet, they’re left outside.

This should be a service for everyone.

The institutional framework is both promising and precarious.

In 2023, Gustavo Petro’s government explicitly included harm reduction, for the first time, in Colombia’s National Drug Policy, a ten-year plan grounded in public health and human rights.

The document doesn’t discard the traditional objectives, such as reducing coca cultivation, but it introduces a new grammar. In theory, it opens a path for initiatives like Cambie; in practice, the road ahead is long — and the ground remains unsteady.

Across the Atlantic, a rare gesture. In March 2025, at the 68th session of the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs in Vienna, a resolution led by Colombia’s ambassador Laura Gil passed, calling for an independent body to review the global drug control system — “which is not working,” she said bluntly from the heart of the diplomatic stage.

“Colombia supplies less than five percent of the world’s illicit drug market. We’re not proud of this reality — but why should every Colombian feel that the world’s drug problem rests on their shoulders?

This panel is an invitation — within the framework of the conventions — to rethink our approach, to truly embrace the principle of shared responsibility. My country has sacrificed more lives than any other in the war on drugs imposed on us. We’ve postponed our development, committing our best men and women — and a significant share of our national budget — to the fight against drug trafficking.

We want new and more effective ways of applying the global regime. This should not be a confrontation among us, the members of the CND, but a reflection of our common commitment to fight transnational crime,” Laura Gil said — and, for a few seconds, the room seemed disarmed by her words.

It’s a diplomatic gesture with domestic repercussions. By challenging the international regime, Colombia lends — however indirectly — a measure of legitimacy to local experiments like supervised consumption sites.

In June 2025, days after defying convention at the UN, Laura Gil resigned as Colombia’s ambassador to Austria — only to become the first woman ever appointed Deputy Secretary General of the Organization of American States.

But as the sources interviewed by Thornton warn, there’s a chasm between the victories on display and the execution behind the counter — a history of erratic budgets, scarce transparency, and, in 2020, almost zero official funding for harm-reduction efforts, according to the Global Drug Policy Index.

The warning light stays on.

The diagnosis is blunt — and corrosive: without stable funding, public policy turns into a perpetual pilot project.

So where, then, is the money supposed to come from?

Thornton identifies three main sources of funding: assets seized from drug trafficking; revenue from state-controlled morphine sales, funneled through national narcotics funds; and local government budgets.

A mosaic of origins, disparate, fragile, and never entirely reliable.

In practice, the flow of resources is intermittent and often skewed.

Funding tends to favor programs designed to reduce injectable drug use, while neglecting strategies such as drug checking, supervised consumption sites, and evidence-based education — the very tools that keep people alive.

Julián Quintero, of Acción Técnica Social, estimates that the national government allocates at most 300,000 dollars a year to harm-reduction programs.

As a structural alternative, he proposes earmarking 4 to 5 percent of tax revenues from tobacco, ultra-processed foods, and alcohol for prevention, care, and treatment — a fiscal loop where what harms could also help to heal.

Cambie’s balance sheet exposes the dilemma with striking clarity: about 25 million pesos a month — roughly 6,500 dollars — currently covered by the Open Society Foundations.

Meanwhile, the number of registered users keeps growing: 88 as of May 2025, and the NGO is already looking for a larger space.

A survival budget sustaining a politics of life.

On the international stage, as Thornton reminds us, the story carries both echoes and contrasts. Supervised consumption sites first appeared in Switzerland in 1986, then took root across Europe — in Denmark, Portugal, the Netherlands, Germany, and Spain — before expanding to Canada and the United States, with New York at the forefront. Ireland is expected to open its first site soon.

In Bogotá, the Colombian model carries a distinct DNA — shaped by social justice and human rights, as the researchers interviewed by Thornton describe it. In the United Kingdom, by contrast, a more medicalized model prevails — less open to community experimentation, and constrained by narrower institutional boundaries.

This isn’t a theoretical observation. It’s a warning about institutional design — about who provides care, in what language, and with what vision of the future.

Between the macro and the micro, there is Cali, where a second site is soon to open, run by another organization, Corporación Viviendo. The expansion signals vitality; the legal gray zone, meanwhile, reminds us that this policy still depends on the will of a few allies.

In such a fragile field, that dependency becomes a systemic risk: leadership changes, and the winds shift.

What remains is the body — and bodies can’t wait for the electoral calendar.

For many, there’s also an ethical question about what, exactly, is being celebrated.

Thornton writes in a journalistic register, transparent about potential conflicts of interest — she was a media fellow at HR25, the 28th International Harm Reduction Conference held in Bogotá from April 27 to 30, with travel and lodging funded by a philanthropic foundation. She presents Cambie not as a miracle, but as a working hypothesis.

The honesty of method matters.

Harm reduction is not about absolving substances; it’s about refusing to accept death as the cost of policy.

Far from “liberalizing” use, harm reduction governs more wisely — so that fewer people die.

And the opening scene returns — like a compass, pointing not north, but toward the possibility of care.

At Cambie, beyond syringes and mirrors, there is the quiet work of rebuilding ties: support for housing, legal guidance, access to healthcare, psychosocial aid, family reunions, warm tea, biscuits — and, when the wound comes from the street, bandages, care, a place to rest.

As Daniel explains, the principle is simple: if someone just wants to rest, to have peace and quiet, they can. The work isn’t transactional; people truly matter there.

The sentence is simple, but it shifts the axis of the debate.

Where policy usually counts hectares of coca or tons seized, harm reduction measures something else entirely: dignity.

And dignity, when offered with method and consistency, becomes public policy that works.

Here, dignity isn’t abstract. It is a measurable indicator — a new standard of institutional accountability.

When empathy becomes the focus, the lens shifts. Cambie doesn’t demand abstinence; it expands capacities — the capacity to live, to work, to care for oneself, even when drug use continues.

The central metric is no longer compulsory renunciation, but substantive freedom.

If we follow Bruno Latour (1947–2022), the room becomes a network of actants: mirrors that “see” doses, ambu bags, naloxone, intake forms, peers, technicians, community police, neighbors.

In the vocabulary of Actor-Network Theory (ANT), actants are agents — human or not — that participate in producing social reality.

For Latour, society is not made up of subjects alone, but of dynamic networks in which objects, norms, tools, and bodies act together — translating, negotiating, and redistributing forces.

Drug policy, then, ceases to be an abstraction and becomes a socio-technical arrangement — a space where each component translates and mediates values: care, control, risk, dignity.

A climatic choreography of forces, constantly negotiating the fragile balance between survival and the rules meant to govern it.

The climate of dignity, calm, and trust shifts the consumption space from a disciplinary non-place to a site of recognition.

Here, American medical anthropologist Paul Farmer (1959–2022) helps us think: structural violence operates precisely by pushing risk onto the most vulnerable.

Grassroots community services like Cambie do not abolish that logic — but they loosen its grip, releasing accumulated harm and redrawing the contours of care where once there was only punishment.

Donna Jeanne Haraway (1944–) helps here, too: “all knowledge is situated” — produced from embodied, socially located, and politically implicated standpoints. That claim unsettles the myth of neutral, universal objectivity and demands accountability for the effects of what we call truth.

Colombian creativity — peer-led care, non-transactional support, radical welcome — arises from a specific urban ecosystem. And it is no less scientific for that.

On the contrary, it shows that when knowledge is born of life, it changes what it touches — and changes us.

In the end, the Colombia illuminated by Thornton takes shape as a laboratory of the future: a diplomacy that, in Vienna, dares to repair a stalled international system; a national policy that, for the first time, inscribes harm reduction into its founding text; and a city that, with a handful of mirrors and a few vials of naloxone, has saved fourteen lives in a single year.

It’s not much, some will say.

It’s a beginning, we might reply.

Between the syringe and the law, there are people.

And that is where history, truly, happens.

* * *

How to Read Impact (Without Illusions)

A critical reading hinges on three questions:

Does it work?

Yes. It saves lives (14 overdoses reversed), expands access to services, and reframes drug use within a rights- and health-based framework. These are plausible, documented effects.Is it scalable?

Not yet. Without a stable funding base, it remains an island. Earmarking “sin taxes” is one institutional pathway. But monitoring — better data, clear process metrics, and outcome tracking — must improve to guide any meaningful expansion.Is it transferable?

Partially. Every city has its own ecology. Still, core principles travel: peer-based bridges, nonjudgmental care, clean kits, accessible naloxone, aligned diplomacy. It’s no coincidence the world already runs 150+ supervised consumption sites across 18 countries, each a variation on the model.More info: https://www.acciontecnicasocial.com/

Contribute: https://arc.net/l/quote/wiasvzby