The Purity Regime: Liturgy

(1/3): After COP11, the treaty stands still, like scripture. Around it, power flows — fluid, moralized, perilously clean.

The treaty remains untouched, like a sacred relic no one dares disturb. Yet around it, everything shifts with brutal precision: power extends its tentacles, norms harden into unquestioned dogmas. And people, they dissolve into data points and percentages.

This is the unwritten legacy of COP11.

The quieter the treaty, the farther it reaches. The more technical its language, the more deeply it embeds itself in daily life, not as law, but as a condition.

The Eleventh Conference of the Parties to the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control revealed how a regime can grow without ever changing its name. How it expands without confession. How it silences dissent not through force, but through structure, ensuring it never truly enters the room.

The title remains. The substance does not.

I was in Geneva during those days. I watched doors close with choreographed precision, heard the breathless pause between simultaneous translations, and walked corridors where delegates kept their eyes low and their voices lower, speaking only through their paper cups, their shoes, their fatigue.

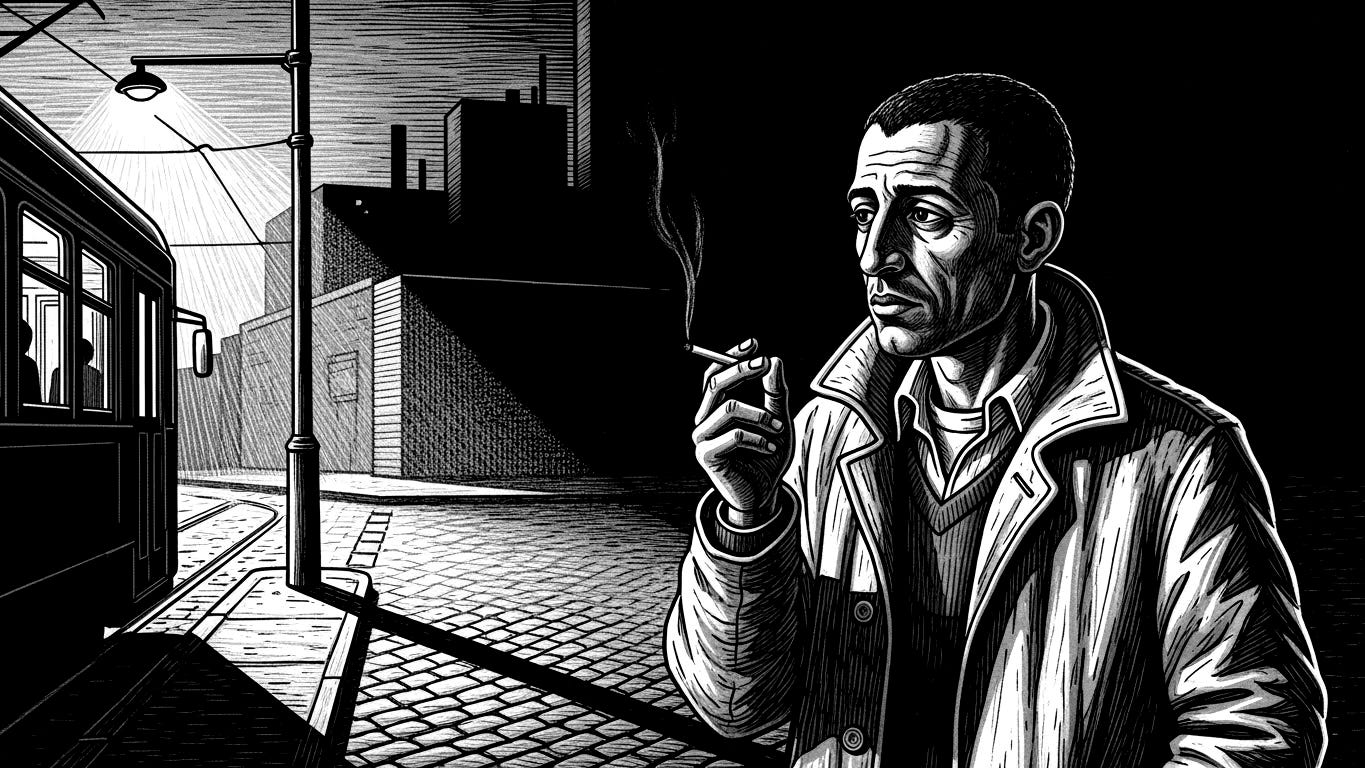

Outside, in the cold, among cigarette butts no one had swept away, I encountered a form of power that no longer needs to be written to rule. It governs in silence. It survives by habit. And it endures, unnoticed, in the grain of everyday life.

At first glance, COP11 appears to be a technical gathering: neutral, objective, functional. But its rituals betray another nature: a form of power that moves through repetition and gesture, not proclamation. In this first part, we follow the path where protocol becomes performance; where doors close in synchrony, and decisions seep into daily life as if they had always been there. The liturgy of control begins, as most liturgies do: in silence.

The Fading Glow and the Ending That Feels Routine

When the final session ends, the interpreters remove their headsets like someone unplugging a life-support machine. The delegates shut their metallic laptops. The conference logo disappears from the big screens. There is no applause. Only the dimming of the lights.

Outside, the wind sweeps across an almost empty parking lot. In the distance, the white mass of Mont Blanc stands where it always has. Colossal. Indifferent to the fate of a comma, to the semantics of clauses, to the choreography of draft texts. Indifferent to the language that seals, by consensus, an opacity no one dares name — not even in a whisper.

The building empties with the expected precision of Swiss efficiency. Trash bins are replaced. Side doors opened with care. Badges still sway on the chests of those who agreed out of faith, fatigue, or the quiet sense that it was already too late to disagree. Out of conviction, convenience, or exhaustion, even the architecture seems to comply. In the cracks, the wind whistles like a rule, marking the beginning of winter.

The concrete of the Centre International de Conférences Genève carries no trace of grandeur. It shows wear. Straight lines. A canopy far too wide for the modest flow of people.

Above it, the name stretches in cold lettering — CIG. Above that, a colorful COP11 banner attempts to manufacture celebration, where everything insists on protocol.

The regime does not announce itself with grandeur. It announces itself with normalcy.

It was there, between the faded screen and the canopy, that something less modest took place. Something the translucent badges and the sobriety of blue, white, and gray folders never quite disclosed.

Delegates passed in silence, in trios, in pairs — steps short, measured, almost solemn. Golden pins placed with geometric precision on lapels. Hair buns pulled tight enough to stretch skin. Ties centered with bureaucratic vanity, to the millimeter. Polished leather shoes with discreet soles glided over thick carpet, muffling the sound of everything.

An aide adjusted his headset even outside the room. A staff member folded papers as if folding a flag. In the background, a technician powered down the conference totem, switching off one light at a time, until only the blank screen remained, as if erasing a name with tweezers, letter by letter, leaving no trace.

Everything looked provisional. Nothing was.

Millions of deaths; billions of dollars

Between November 17 and 22, 2025, Geneva hosted the Conference of the Parties to the World Health Organization’s global treaty, a legal instrument that, for over two decades, has shaped fiscal, health, and regulatory policies on everything related to tobacco and, more recently, nicotine.

A conference that reads as technical. But one that regulates gestures, rhythms, and routines, even before it is understood.

Almost every country in the world has joined the Convention. Together, at least on paper, they manage an epidemic that kills around eight million people a year and circulates hundreds of billions of dollars in taxes, profits, and illicit trade.

In theory, the COPs present themselves as technical meetings: delegates lined behind color-coded nameplates, interpreters enclosed in glass booths, decisions sealed by consensus and crystallized into discreet documents titled in legal English.

On the stage of neutrality, the paper is clean and clear. The bodies backstage are not.

It’s enough to watch the subtext of restrained gestures. The weight of the headset on the ears, the way the body learns not to react in public, to sense what’s at stake: the daily future of countless lives, and what may be sold, smoked, vaped, taxed, or banned across much of the planet.

The COP is not merely a forum. It is the apex of treaty decision-making that cuts through multibillion-dollar economic chains and regulates habits inscribed in billions of bodies.

The path to the entrance offers no spectacle. It offers sidewalk.

Between the body and the canopy, there is a corridor of asphalt and dry leaves, a passage where the body crosses from the common world into the space of governance, standardization, and control. Yellow scattered across the ground. Nearly bare branches. The building ahead rises like a concrete block, heavy, slow, unwelcoming.

To the right, cars aligned with the discipline of the curb. To the left, vegetation already bowed to winter.

The event begins there, before the door. The world narrows, grows straighter, grayer, more administrative.

Life is being arranged into a path. One foot after the other. One badge after the other.

As I reach one of the side exits, I think of the precise choreography of the final documents; decisions recorded as unanimously approved, with no trace of dissent, no mention of internal tension.

I think of a policy refined in a lab. And then I remember the delegate who had crossed my path just minutes earlier, wearing the blank stare of someone who has spent hours in closed sessions. He paused, just for a second, as if calculating the presence of an invisible camera, and said, in a low voice:

“I’m forbidden to speak to the press.”

Forbidden.

The word clung to his coat.

Outside is the Farthest Place in the World

I walk beyond the perimeter of the badges. And the world reappears in simpler signs, less ambitious, more honest: tracks, timetables, signals. People meeting. People returning from the week’s shopping.

The tram stop remains in the exact location. Indifferent.

An orange train pulls in and departs with the regularity of something that doesn’t need a plenary to function. On the asphalt, the imprint of a bicycle. On a pole, a blue sign with the figure of an adult and a child, a pictogram of care that requires no consensus, produces no report, and becomes no directive. It simply signals what already exists. And keeps existing.

Out here, politics becomes this again: movement, fares, hurried steps, shopping bags over the forearm, cold hands, time measured in minutes. Inside, they debate “emission,” “product,” “regulation,” and “prohibition.” Out here, the body just wants to arrive.

Less than three hundred meters from the main entrance, already beyond the event’s geometry, another building displays its mission with no subtext: UNHCR, in large blue letters on a curved façade. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, written at the top. Physical proximity only shortens the moral distance. So it can be exposed. Institutions can be neighbors and still inhabit ethically separate worlds.

The wind doesn’t know the difference.

Henri Smokes and Doesn’t Read Resolutions

It’s in this stretch of the city, between signs and institutional facades, that I meet Henri. No badge on his chest. Just a body exposed to the cold and to the rules. An invisible part. A French-Maghrebi worker in a cheap jacket, a lit cigarette between his fingers, waiting for the tram. The pack appears and disappears in his left hand like an informal document.

I strike up a conversation at the stop. He answers kindly, without the trained reflex of no comment.

I say — more out of habit than necessity — that I’m heading to Cornavin. I mentioned that I had just come from a conference organized by the WHO. Henri has never heard of the FCTC. When I say COP11 and gesture toward the cigarette between his fingers, he looks at me with mild curiosity, like someone watching an aquarium.

But he smiles when I say I’m from Brazil, more precisely, from the deep south, the same city as Ronaldinho Gaúcho.

Then he shows his teeth and bursts out:

— Ronaldinhooo… ufff… il est ouf!

Diplomacy, for a moment, becomes a joyful caricature.

It doesn’t last.

The cold returns.

The pack Henri holds no longer costs what it once did. Prices have climbed — along with taxes, illness rates, warnings, and the quiet cost of habit. Charts follow, filled with numbers no one reads aloud. He knows, with the indifferent lucidity of someone with little room to choose, that smoking is harmful. He shrugs. Inhales deeply. Exhales into the frozen air.

Four dark-tinted vans cross our field of vision in the opposite direction, perhaps en route to some diplomatic mission. They pass without the sound of voices, as if the city had opened a corridor.

Henri stubs out his cigarette with the sole of his shoe. I, instinctively, keep my vape hidden between my phone and the palm of my hand. A small act of concealment. A small piece of theater.

The scene ends with a detail COP would ever record in their minutes, but that explains everything. At the entrance, a metal ashtray overflows with crushed cigarette butts: flattened filters, damp paper, accumulated ash. In the background, blurred, the colorful “COP11” logo floats like a clean seal over a dirty remainder. The image is indecent and simple: the regime debates public health in abstraction; the body leaves residue on concrete.

Silently, I send a nod to Edoxie Allier — for the photo.

Henri boards the number 8. I wait for the 5.

The bus comes. Mont Blanc remains.

We inhabit dead zones, dissolved into data packets.

And the question before the dinner now is not metaphysical, it’s logistical: What does normative language actually reach, once the substance is already on the ground?

They have forgotten the most important person, the end user. As you so well point out.

It needs to be about saving lives, that should be the primary goal, the only goal... Instead of all that, whatever it is...