The “Other” COP

“All About Us Becomes Policy Without Us”

While official delegations seal opaque consensuses, on the fringes of COP11 a parallel gathering brings together scientists, users, and public health dissidents to rewrite the rules of care—guided by data, not doctrine. A silent insurgency on the margins, seeking to rescue science from moralism and care from bureaucracy.

A few minutes away from COP11, where the language of public health reverberates as a hollow, technocratic mantra, another conference is quietly taking shape. Heterogeneous, informal, almost clandestine, it emerges on the periphery of the official event as a deliberate countercurrent, a necessary deviation.

But it is anything but marginal.

What is forming in these less-patrolled corridors is not a frontal rebellion against the Conference of the Parties on Tobacco Control. It is, rather, an internal pressure point. It shares the same battlefield but speaks a different lexicon, moves to a different rhythm, breathes a different air. Inside the Geneva International Conference Center, the future is translated into spreadsheets and clauses that mimic clarity. Here, time is grounded in the visceral present.

The contrast could not be starker.

On one side: the ceremonial choreography of government and health officials, their speeches orbiting predictable platitudes, their doors closed, their scripts aligned.

On the other hand, a gathering of scientists, physicians, harm reduction advocates, public health experts, and ex-smokers (some with ties to the feared industry; many, suspended between statistics and lived experience). They speak a different grammar, one that still dares to ask whether science can be more than ornament, whether it can be reclaimed as a legitimate language of care. Not doctrine, but data. Not slogans, but inconvenient questions.

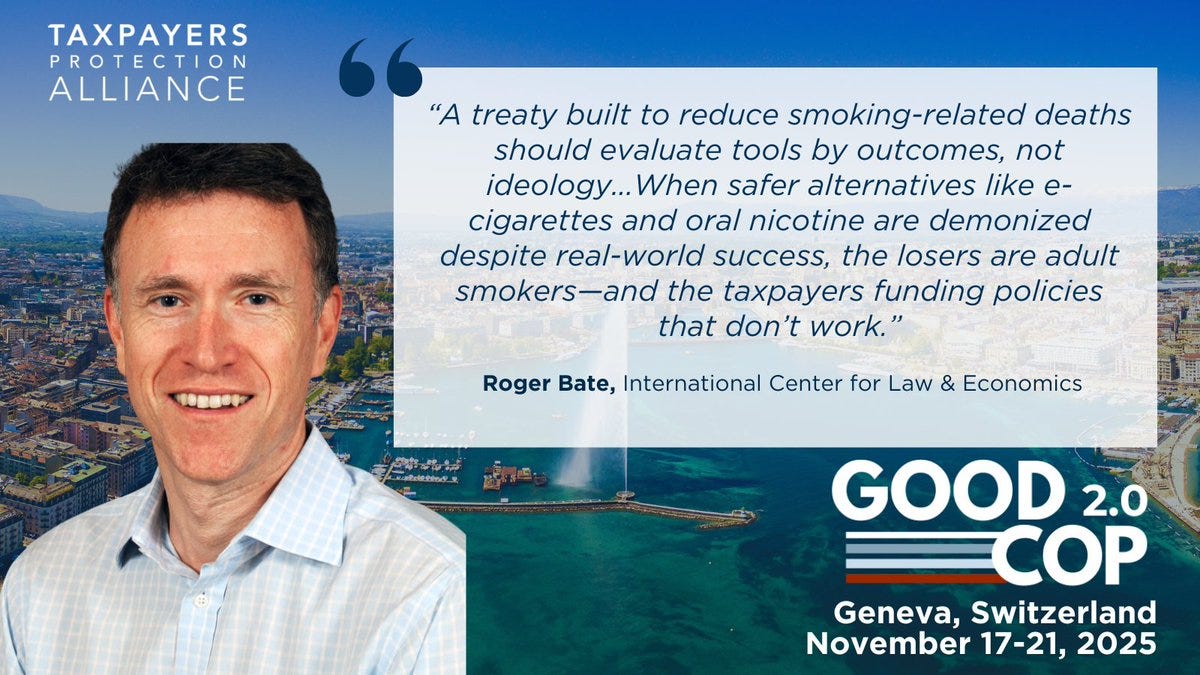

At the center of this gathering stands Martin Cullip and David Williams, the event’s principal hosts. His presence anchors the agenda and sets the tone: open, evidence-driven, unafraid of difficult conversations.

The event calls itself the “Good COP.” At first glance, the name is sheer irony. But as the radical heterogeneity of its participants unfolds, the adjective begins to shift. From sarcasm, it becomes a hypothesis. From provocation, a question: What if the “good” conference isn’t the official one?

Its core is a deliberate rupture: trading moralism for metrics, grandiose rhetoric for grounded evidence. Its mission: to reduce disease by targeting combustion where it truly burns—not where political convenience gestures.

Its logic is clinical, not catechetical. And what falls outside this criterion, performative bans, colonial policies transplanted without context, campaigns wrapped in doctrinal zeal, is treated as what it is: noise disguised as virtue.

What is taking shape is more than an event. It is the sketch of a new cartography: a map of dissent. A convergence of voices from scattered geographies, staking a claim on the center.

Who will speak with whom? From where? And with what urgencies?

As the gathering makes clear, what is at stake is not just science. It is the right to use science as a language of care. And, perhaps, of insurrection.

The Historical Fold: Pangestu and the Body of Dissent

Tikki Pangestu moves through the Good COP not as an institutional figurehead, but as a dissonant memory made flesh. Formerly the Director of Research Policy & Cooperation at the World Health Organization, he was at the table when the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) was conceived, a moment of regulatory idealism still etched into the global health narrative. But two decades on, he returns not to commemorate that achievement, but to interrogate its consequences.

His presence is not ceremonial. It is a living friction.

Pangestu does not function as a bridge between past and present; he is the rupture itself. His body is a site of paradox, both author and critic of the system, emblem of its aspirations and its betrayals.

On Monday, November 17, at 10:00 AM, he opens the Good COP’s first day in a public conversation that sets the tone for what follows. It is not a nostalgic reminiscence, but a sober and lucid questioning of what became of the treaty he helped draft.

Then, on Wednesday, November 19, at 10:30 AM, during the Asia Day keynote, his voice returns with even greater force. This time, not to critique the past alone, but to articulate a future rooted in the region he calls home. With clarity, he repositions Southeast Asia not as a passive receptor of Western prescriptions, but as a generative source of science, agency, and normative power.

This is not just symbolic revisionism. It is an epistemic insurrection, a deliberate reversal of the flow of authority from North to South. And it comes with a sharp critique: that the FCTC, once envisioned as a flexible framework, now stands eroded by ideological rigidity, conditioned funding, and a bureaucratic fog that shields itself from accountability.

What Pangestu performs and personifies is not nostalgia. It is dissent. Rooted, lucid, and anatomically precise.

Dissecting Article 2.1

Alongside Cullip, Clive Bates operates as the institutional surgeon of the event. Formerly the director of Action on Smoking and Health in the UK, he stands as one of the most incisive and discomforting critics of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. His strength lies not in theatrical denunciation, but in methodical dissection: exposing the bureaucratic musculature with the steady hand of someone who has spent decades navigating and dismantling its logic.

His first scheduled intervention, set for Monday, November 17, at 2:00 PM, will unfold in a high-stakes panel dedicated to Article 2.1 of the FCTC.

Originally envisioned as a “freedom clause,” meant to give countries the liberty to go further in protecting health, it is now—according to Bates—at risk of mutating into a subtle instrument of coercion. What was drafted as a shield for regulatory autonomy may be deployed as a scaffold for soft mandates: obligations camouflaged as options, ratified through ambiguous consensus.

This is no longer prohibition by decree, but induction by protocol, without transparency, without democratic accountability.

Moderated by Martin Cullip, the session is set to bring together a constellation of voices from diverse geographies, including Kurt Yeo from South Africa, who cautions against policy transplantation devoid of local context, and Juan José Cirion from Mexico, who questions the creeping erosion of national sovereignty through supranational guidelines. Each voice brings its own urgency, but it is Bates who promises to thread the anatomy of the treaty with scalpel-like precision.

Few can render the invisible visible as Bates does: regulatory capture, semantic distortion, the alchemy of language used to manufacture consent. Yet his intervention doesn’t rest solely on critique. Like a skilled surgeon, his gesture is also reconstructive. He argues for models of regulation grounded in informed consent, not moral panic; policies that mitigate risk without imposing abstinence. A framework anchored in science rather than stigma.

At the core of his appeal lies a simple imperative: to restore the severed link between policy and consequence, the juncture where well-meaning public health ideals, when severed from evidence, often mutate into unintended harm.

The Battle for Science

Among the densest blocks of the Good COP, one upcoming panel doesn’t just stage a debate; it draws a frontline. Set for Tuesday, November 18, at 1:00 PM, it brings together voices from Canada, Mexico, Greece, and Malaysia: four geographies, four scientific traditions, united by a shared gesture of methodological insubordination.

Mark Tyndall, a Canadian epidemiologist shaped by the frontline of the opioid and HIV crises, enters the nicotine debate with a disarming maxim: less combustion, more life. A phrase so simple it startles, devastating in its clarity. It condenses decades of experience confronting policies that mistake moral purity for public health efficacy.

Roberto Sussman, a professor and physicist from Mexico, brings a different arsenal: mathematical modeling and aerodynamic analysis that dismantle the straw man of “passive vaping” with precision. His argument is not militant, but methodical: confronting the strategic silence of institutions like the WHO, which routinely sideline physics and chemistry when they disrupt the dominant narrative.

Konstantinos Farsalinos, a cardiologist from Greece, provides the clinical and laboratory backbone of harm reduction science. His body of work spans multiple studies that have been systematically ignored in recent COP editions. The science exists; it simply circulates in the wrong direction.

Sharifa Ezat Wan Puteh, from Malaysia, widens the aperture. She introduces cost as an ethical variable, noting that access, effectiveness, and inequality are not peripheral considerations; they are the very foundation upon which any serious public policy must be built.

Moderated by Marina Murphy, the panel outlines a technical arc that spans continents and, if actually heard, could fracture a persistent myth: that “science” is the exclusive property of the Global North and its official conferences.

These scientists are not merely demanding a seat at the table. They are demanding authorship and voice over the evidence that defines what health means, and for whom.

From the Margins: Philippines, Thailand, Nigeria, Costa Rica

One of the most radical gestures at the Good COP may not emerge from labs or spreadsheets, but from the insubordination of bodies. Not from scientific proclamations, but from those who live at the receiving end of policy.

These voices will appear across several sessions between Tuesday, November 18, and Friday, November 21, including the Consumers Showcase, the Asia Day plenary on user perspectives, and discussions on consumer agency and exclusion. Together, they form the informal backbone of the Good COP’s most politically urgent panels.

Figures like Clarisse Virgino (Philippines) and Asa Saligupta (Thailand) are expected to speak not as isolated cases, but as “organized users”, a category that resists two simultaneous erasures: the criminalization born of prohibition, and the paternalism of institutional charity.

Joseph Magero, from Nigeria, brings this resistance into sharp relief within African contexts, where the informal economy often sustains life, and law enforcement governs daily existence. In such realities, importing health policies designed in Geneva or Brussels approaches epistemic violence. The rules arrive heavy with normative weight, but context is never shipped with the box.

From Costa Rica, Jeffrey Zamora adds a mestizo register: equal parts advocate, content creator, and civic strategist. As president of his country’s vapers’ association and chair of key sessions, his presence spans testimony and tactical articulation. He is not petitioning for attention; he is asserting authorship.

These voices, and many others, are not coming to present themselves as victims. They are not seeking charitable inclusion, but agency. They demand not just a seat at the table, but participation in drafting the blueprint. And they are seasoned. They know that from the margins, you don’t wait for permission. You redraw the map and name the coordinates yourself.

Sweden as a Living Question

If there is one case that can strain, or even collapse, the moralistic edifice of global nicotine regulation, it is Sweden. In a panel scheduled for Thursday, November 20, at 1:00 PM, Bengt Wiberg —inventor, entrepreneur, and former smoker—is expected to present the country not as a model to be replicated, but as an uncomfortable anomaly.

Sweden has reduced cigarette consumption through a formula that defies the prohibitionist script: oral nicotine products, pragmatic regulation, voluntary adherence. No crusades. No coercion. Just effectiveness.

His innovation, the Stingfree/PROTEX device, will likely be presented both as a technical solution and a political allegory. It embodies a thesis many regulators refuse to confront: that it is possible to reduce harm without reproducing punishment. That regulation can be intelligent without being intrusive.

The Swedish case is not a doctrine, nor a fetish. It is a living question—one that doesn’t ask, “Why isn’t this exported?” but instead: If it works there, what within us—our institutions, our ideologies, our aversions—prevents it from working here?

America of Good Intentions; and Predictable Tragedies

In the panel titled “THR in the Americas: Fury, Failure and the FDA”, scheduled for Thursday, November 20, at 2:00 PM, the paradox is set to surface in its rawest form: while vaping is criminalized, cigarettes remain legal and omnipresent. Jacob Grier and Jeff Smith, both from the United States, are expected to expose this dissonance with forensic clarity, showing how public policy punishes the less harmful alternative while, through inertia or convenience, protecting the deadliest habit.

Dr. Mark Tyndall, already a familiar voice in the scientific panels, will likely return with data too stark to dismiss: the surge of illicit markets, preventable relapses, and the judicialization of what should be a matter of health, never one of crime. Although Roberto Sussman is not slated for this session, his earlier contributions will be echoed here, particularly in highlighting how bad science can metastasize when politics refuses to accept evidence.

Officially, the panel invites reflection on “unintended consequences.” But the irony will be hard to miss: when science is systematically ignored, harm is no longer a side effect.

It becomes public policy, with a taxpayer ID, a bureaucratic seal, and victims dressed as offenders.

When Money Writes the Whole History

In what promises to be one of the sharpest panels of the Good COP, scheduled for Thursday, November 20, at 11:00 AM, the discussion centers around a term that most international institutions dare not speak: philanthro-colonialism. The accusation is direct, and it comes from within.

Jeannie Cameron is expected to dissect the FCTC not merely as a treaty, but as the diplomatic machinery that produces its silences. This is not just about what gets signed; it’s about who drafts the language, who controls the funding, and whose interests are embedded in the clauses left unsaid.

From New Zealand, the tireless Nancy Loucas will likely expose a brutal symptom of this asymmetry: Pacific nations signing onto health policies they didn’t author, because the language arrives prepackaged, bound to funding, wrapped in benevolence. It’s not consultation; it’s compliance by design.

Marina Murphy and Reem Ibrahim are expected to deliver the final synthesis: a regulatory ecosystem where “communication,” “partnership,” and “capacity-building” operate less as dialogue and more as mechanisms of capture. Grammar itself has become a tool of domination: strategic, sanitized, and tax-deductible.

Here, the critique flips the usual vectors. It does not rise from the South as a resentful indictment. It originates in the North and returns South, spoken by those who feel the consequences not in theory but in budgets.

And in their breath.

Europe: The Norm Factory

The panel scheduled for Monday, November 17, at 3:00 PM, focuses on the EU’s TPD/TED review and the WHO’s influence in Europe. What’s expected to surface is not merely a critique of health directives, but a forensic mapping of a regulatory engine: distant, opaque, and insulated from democratic feedback.

Alberto Hernández, Adam Hoffer, Benjamin Elks, and Carissa During are set to expose how norms crafted in Geneva cascade across the continent with the force of orthodoxy, technically precise, politically detached. Authority asserts itself; reciprocity does not.

The language of “health protection” will likely appear as a facade for regressive outcomes: tax schemes that disproportionately punish the vulnerable, visual warnings that alarm rather than inform, and the acceleration of illicit markets amplified by the very opacity of the rules meant to contain them.

What’s anticipated, then, is not a technocratic debate, but a structural impasse: a system where the complexity is not incidental, but strategic. Probably the question that may linger after this panel is not just “who profits from complexity?” but “who normalizes it, and who is allowed to escape its consequences?”

“All About Us Becomes Policy Without Us”

In one of the final, and most politically charged, panels of the Good COP, scheduled for Friday, November 21, at 11:00 AM, Mark Oates, from the UK, is likely to lead a dissonant yet sharply articulate chorus, featuring voices from Chile, Thailand, Croatia, Nigeria, and the Philippines.

There will be no metaphors, only presence. These are organized users, not summoned as props to decorate data, but stepping forward as protagonists demanding authorship in the making of policy.

The demand will not be for symbolic inclusion, but for real co-authorship. The message will be unmistakable: to exist beyond the label of “victim,” to reject institutional guardianship, and to claim, in their own voice, the democratic agency of decision-making.

At this moment, geography is expected to shift from backdrop to method: a transversal arrangement linking the Global South, Eastern Europe, and Southeast Asia. Not through shared identity, but through shared exclusion. A cartography of marginality turned method. A map that refuses the permissions of the Geneva–Brussels axis. A map etched into real bodies in breath, in scars, in persistence. And for that reason, it cannot be ignored.

Politics That Breathes Life Outside the Palaces

To breathe here is more than biology or metaphor. It is a political act. A choreographed refusal. The Good COP is not to be observed as a side event, nor archived as a footnote. If it fulfills its intent, it will act as cartographic insurgency: a rehearsal for embodied politics, driven by those who bear the consequences, grounded in evidence, and animated by the urgency of those who cannot afford to wait.

On the margins of the official conference, what is expected to emerge is not a new consensus, but something far more unsettling: a living record. A volatile territory composed of voices, of productive dissent, of questions that do not merely speak, but think, and breathe, together.

A space where science might recover its ethical muscle: care for life as it is, not as doctrine imagines it.

If FCTC/COP still hesitates, this other gathering will already have left its mark: not as background noise, but as a symptom. And perhaps, as a path forward.

All sessions are expected to be streamed live and openly on YouTube, unlike the official COP11, which will be held behind closed doors.

Good COP / Full Agenda: https://www.protectingtaxpayers.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Media-Fin-2.0-Updated-agenda-2.pdf

Great summary of Good Cop by Claudio.