Smoke in Peers: The Lab-Crafted Thermal Failure

A technical paper on e-cigarettes quietly dismantles the experimental foundation of part of the risk literature, and suggests we may be measuring burnt cotton, not human behavior.

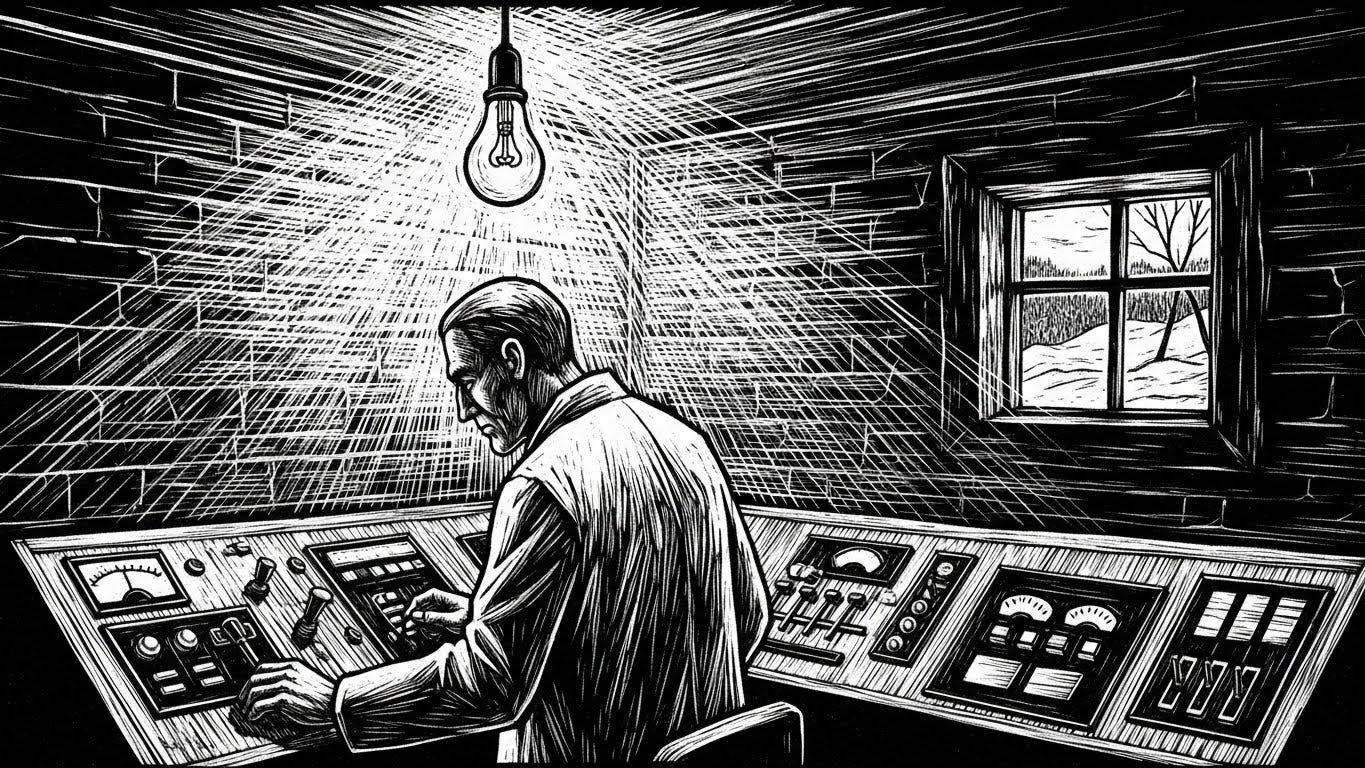

Between the lab bench and the lung, there’s a button. Sometimes just a number on a flow controller. It determines the amount of air that flows in, the amount of heat that accumulates, and the type of aerosol that is released.

The cell reacts. But to what, exactly? In a critical review, two researchers propose that a portion of preclinical studies may have tested not human use, but a state of overheating: an aerosol generated when the device exits its stable operation, something users describe as unpleasant and tend to avoid, but which, in standardized protocols, may end up being treated as representative of the habit.

A high-powered vaporizer (the sub-ohm kind, used in direct-to-lung mode) should not be mistaken for a generic “e-cigarette.” It’s a small, high-precision machine sensitive to two variables that determine its fate: whether to evaporate or degrade. Air and liquid, or the unstable balance between them, decide everything.

A coil heats a cotton wick soaked in e-liquid. The aerosol, in turn, doesn’t arise automatically. It’s the result of a continuous negotiation between heat and moisture replenishment. A kind of precise pact, balancing the avoidance of overheating with the preservation of equilibrium.

The agreement is simple: enough airflow to dissipate heat; enough wicking to keep the cotton moist. But when either condition fails due to misadjusted power or airflow, delayed liquid replenishment, or a protocol that imposes low flow rates on a device built for voluminous draws, the nature of the “vapor” shifts.

Instead of efficient evaporation, the system begins to operate at the edge of overheating. The aerosol ceases to be a mere proxy for use and, however unintentionally, begins to undergo thermal degradation.

Airflow passes through the coil assembly during the puff and prevents heat from accumulating like a fever with no escape valve. Wicking is the other half of the thermodynamic pact: the cotton’s ability to reabsorb e-liquid quickly enough to avoid drying out.

But this balance is fragile, always near collapse. Increase the power and restrict the airflow, or, in the lab, keep flow rates below what these devices require, and the “optimal” operating point shrinks dangerously. The cotton dries out, the coil begins to boil abnormally, and the chemistry reconfigures. Carbonyl compounds, including aldehydes, tend to emerge signaling that the transformation has shifted from the physical to the molecularly suspicious.

Users have a name for the moment taste exposes failure: dry puff. A burnt-tasting draw described as repulsive and invasive, and consistently avoided. But what the body rejects, the protocol accepts: in the lab, the puff is imposed, uninterrupted, immune to discomfort.

It’s in this dissonance between engineering and sensation that a device pushed out of stable operation, generating a failure-mode aerosol, that Sébastien Soulet and Roberto A. Sussman ground their critique of experimental literature. It’s not just a question of technical parameters; it’s a matter of listening to what taste is trying to say.

In their article, Critical Appraisal of Exposure Studies of E-Cigarette Aerosol Generated by High-Powered Devices, published in Contributions to Tobacco & Nicotine Research in December 2025, Soulet and Sussman don’t attempt to answer the question that usually dominates public debate: “Is it harmful?”

They don’t track people, build cohorts, or estimate population-level risk. What they do is more modest and, for that reason, more unsettling: they examine the method.

They treat the aerosol as what it truly is in preclinical studies: the experimental agent. And they ask the essential question: Does what some labs generate to expose cells or rodents physically correspond to what a human user would plausibly inhale? Or is it just a protocol artifact produced by pushing a device beyond its stable regime?

If they’re right, the consequence isn’t a moral verdict, it’s a validity problem. A hypothesis haunts the literature: what if part of what’s being measured isn’t human behavior, but the collapse of a machine?

Soulet and Sussman show consistent evidence suggesting that some of the literature may be measuring machine failure and interpreting it as human behavior.

Their target is deliberately narrow: preclinical exposure studies with recurring experimental setups and specific mechanical limitations. They’re not “re-evaluating vaping” as a population phenomenon. They’re asking, with surgical precision, whether the experimental agent as produced in specific protocols still deserves that name.

The question that frames the article is simple, technical, and almost bureaucratic. But it carries, quietly, a shock: what, exactly, enters the exposure chamber when a study claims to be testing “vape”?

The answer Soulet and Sussman suggest shifts the debate from the moral to the mechanical. In the article, they observe that although consumer use has “overwhelmingly” shifted to low-powered pods and disposable devices, high-powered sub-ohm models remain common in preclinical studies.

Many of these studies employ protocols derived from CORESTA RM81—or close variants—that operate at flow rates of approximately 1 L/min. For a pod, that may be a defensible starting point. For a high-powered sub-ohm device, it may be something else entirely: a setting that narrows the stable operating window and nudges the system toward overheating.

This doesn’t make testing extremes invalid. But it makes it untenable to treat them as normative, or to describe them without making clear the physical regime under which the aerosol was generated. At that point, the error is not merely technical. It’s interpretive.

One Liter per Minute

The article’s technical target is a structural flaw in standardization: when a ruler designed for one type of device becomes a universal rule. In practice, the CORESTA RM81 protocol specifies three-second puffs of 55 milliliters, spaced thirty seconds apart, under constant airflow.

Soulet and Sussman’s critique starts with a detail that seems minor, until it becomes physics: fifty-five milliliters over three seconds equals roughly eighteen milliliters per second, or just over one liter per minute.

For some devices, that’s just the norm. For others, especially high-powered sub-ohm systems, that rate acts as a choke point: it reduces thermal dissipation, narrows the stable operating window, and pushes the system toward the edge of overheating.

At that point, the ruler stops measuring. It starts distorting.

This is why the authors avoid talking “about vaping” in the abstract. Their scope is deliberately narrow, and precisely for that reason, interpretable. The paper focuses on a recurring experimental ecosystem: the InExpose/SCIREQ automated system, repeatedly paired with a single mod—the JoyeTech E-Vic Mini, often running a 0.15 Ω sub-ohm coil.

This isn’t a survey of e-cigarette toxicology writ large. It’s an audit of a specific subset, where the repetition of experimental setups allows for one straightforward question: what kind of aerosol does this method tend to produce?

It’s in that plumbing, not in some abstraction about “vaping”, that the authors locate the critical bottleneck.

The InExpose system, they argue, has a physical ceiling: an instantaneous peak of 1.675 liters per minute, which, over two- to four-second puffs, translates into practical flows between 1 and 2 L/min.

That limit is not an engineering footnote. It’s the line dividing two operational regimes.

With sufficient air, the device behaves as designed: it dissipates heat, maintains thermal stability, and produces consistent vaporization. With insufficient air, it enters a failure mode. The aerosol no longer carries the signature of use; it bears the thermal mark of a system in overheat.

The critique hinges on a point that the authors emphasize: for certain high-powered sub-ohm devices, airflow levels typical of protocols such as RM81 are not merely “low”. They are physically insufficient.

In earlier work, now revisited, they argue that much higher flow rates—on the order of 10 L/min—are required to generate aerosols without inducing device overheating or spiking carbonyl emissions. In this article, that figure isn’t offered as a preference or opinion. It’s framed as an operational threshold, a minimum condition for thermal stability and experimental validity.

When comparing calibrations at 1.1 L/min and 10 L/min, the critique stops being abstract. With more airflow, they argue, thermal efficiency improves, the device stabilizes, and its behavior becomes more predictable.

Even the numbers shown on the mod’s display (voltage, wattage) start to more accurately reflect what’s actually happening at the coil. That level of airflow also aligns with direct-to-lung design: a usage style built on large-volume puffs and low inhalation resistance.

The appeal of the argument lies precisely in its polarization resistance: it’s not moral, it’s mechanical. Too little air, too much power, and low resistance, and the stable operating window shrinks.

In the article’s own vocabulary, the “optimal regime” is one where the mass of vaporized e-liquid increases roughly linearly with power. When that curve breaks its linearity, a low-efficiency thermal regime begins. And that’s when, they claim, carbonyl compounds—like aldehydes—tend to spike sharply.

What the Cell Sees

If the aerosol is the experimental agent, then it, not the study’s title, is what biology responds to. And that shifts the question entirely.

Before discussing “toxicity,” the authors argue, we must ask: what, exactly, was generated to provoke that cellular or animal response?

In the paper, Soulet and Sussman state that, in addition to ten studies they consider virtually irreproducible, at least 31 of the 41 analyzed show signs, direct or indirect, that organisms were exposed to overheated aerosols rich in aldehydes.

A profile not born of randomness, but of a technical pattern: high power, low airflow, low resistance: the triad that steers the experiment into failure mode.

They identify two additional issues that, on paper, may appear to be minor adjustments but critically alter both the dose and experimental realism.

In three studies, aerosols were generated using e-liquids with 30, 36, and 50 mg/mL of nicotine. A choice which, according to the authors, distorts the usage profile: such high concentrations are typical of low-powered devices, not mods running at high wattage.

The result, they claim, is an unrealistic overexposure, both in vitro and in vivo.

The second red flag is the detection of carbon monoxide in the exposure chamber. For the authors, this is unequivocal evidence of advanced overheating, with pyrolysis and oxidation affecting the cotton wick.

This not only compromises the experiment’s thermal profile but also suggests the release of additional byproducts from the cotton, polluting the aerosol and contaminating the experimental agent with residues not present in typical use.

The most delicate move is how Soulet and Sussman link scattered studies to a single conclusion, even when methodologies are poorly described. They built that bridge using two tools: operating curves and calibration curves.

In the operating curves, they argue that under 1.1 L/min airflow (the CORESTA regime), the “optimal regime” for the E-Vic Mini with a 0.15 Ω coil compresses into a narrow range: between 15 and 30 watts.

According to the authors, 30 watts delivered (approximately 35 W on-screen) marks the upper operational limit of that regime. Beyond that point, the device overheats, with signs of film boiling and an exponential increase in aldehyde emissions.

They add a detail that acts as both a sensory anchor and narrative pivot: this transition, they say, would be felt by users as an aversive sensation, something the body learns to avoid, but which the protocol fails to detect.

It’s in the second piece, calibration, where the blow to screen-read trust lands hardest. The paper reports significant discrepancies between the power displayed by the mod and what actually reaches the coil.

In one example, 4.2 volts on-screen corresponds to just 2.85 V measured, yielding 41 W of actual delivered power.

When examining the range of conditions reported across the reviewed literature, the authors observe that real power tends to “touch the ceiling” between 40 and 46 W.

In studies conducted under temperature-control mode, that range is associated with relatively stable, but high temperatures: near and sometimes above 300 °C.

It’s in this overlap, 40 to 46 W, under airflow deemed insufficient, that their critique crystallizes: part of what has been labeled “vape aerosol exposure” may, in practice, be exposure to aerosol generated outside the optimal regime already in the overheating zone.

The Method That Leaves No Trace

The “failure-mode aerosol” thesis makes for a strong headline. But the argument that lingers, and is harder to dismiss, is drier. In many of these studies, the method leaves too little behind for another lab to reproduce what was actually generated.

Soulet and Sussman organize the 41 reviewed articles around a fundamental criterion: can we determine which device was used, which coil, and what power or voltage was applied?

In their taxonomy, “unknown” denotes that the parameters are entirely missing; the conditions are literally unknown. Such studies, they argue, are “completely irreproducible.” Looking at their table, they identify 14 studies at the top of the scale, labeled “Certain,” “Almost certain,” and “Suspicious”, that provide at least minimal information.

Of the remaining 27, 16 offer partial clues that allow for some inference. The final 10 offer nothing at all. To the authors, these are “completely unreproducible”: a “serious methodological problem.” At that point, the issue isn’t whether the aerosol was plausible. It’s whether, in a significant share of the literature, the experimental agent can even be reconstructed.

The article pushes the critique a step further, into a more sensitive terrain: the scientific validation system itself. Soulet and Sussman call this informational void a serious flaw, one that renders a study “essentially unreproducible or impossible to replicate.” But their diagnosis goes beyond what’s missing in the papers. It reaches those who greenlight them.

To the authors, this recurring technical omission reveals a failure in peer review, with reviewers and editors “not attuned” to the physical detail that actually determines what kind of aerosol is being produced.

What’s at stake, they suggest, isn’t just an imprecise data point; it’s an error that shapes the experiment and passes undetected through validation.

There is, however, a significant concession, and here the narrative demands utmost rigor. The authors acknowledge they cannot state with “full certainty” what the operating conditions were in the 27 studies that fail to report minimal parameters. Instead, they speak of a “high probability” that the critique applied to the 14 better-documented studies also applies to the rest.

That inference rests on two elements: the similarity of the experimental setups and the fact that operating the InExpose system requires training, which leads researchers to replicate established procedures.

That fragility, that inference is not fact, becomes part of the argument itself: when the method is opaque, the literature becomes, by definition, difficult to audit. And uncertainty ceases to be an objection. It becomes the most reliable data point left.

The authors’ point is not that “standardization is bad.” It’s simpler, and more demanding: testing extremes is legitimate, even desirable in public health, so long as the paper calls them extremes.

The problem starts when the edge becomes routine by inertia. Or when the method is described so incompletely that the reader assumes representativeness where there was only convention.

If the aerosol is the experimental agent, what’s needed isn’t an adjective, but a schematic: applied airflow, coil type, delivered power (measured, not just screen-reported), puff profile. Without that, a biological result doesn’t lose validity for being “alarmist.” It loses validity for being unrecoverable. There’s no way to reconstruct what, in the end, was actually tested.

The Reach of the Critique and the Data

It’s easy to see why this paper might become a tool in the hands of harm-reduction advocates: it offers a technical key to question studies in which the analyzed “aerosol” may not represent plausible use, but the behavior of a device operating outside its stable regime.

If the exposure was generated under overheating conditions, the biological signals observed may be inflated, and the public debate, unknowingly, ends up arguing over an experimental artifact as if it were a consumer habit.

But the paper’s usefulness hinges on one essential discipline: resisting the temptation to treat it as absolution. Soulet and Sussman do not claim vaping is “safe.” What they argue, within a specific scope, is that there are concrete reasons to doubt the validity of some exposures, and especially how they were described.

The scope is narrow and deliberately repetitive: InExpose/SCIREQ, E-Vic Mini, and often, sub-ohm coils. The authors themselves note that this device architecture no longer reflects typical use. The E-Vic Mini was released in 2015 and is now described as “hard to find” and of “marginal” use.

By 2019, high-powered mods already showed low prevalence (6.3% among youth, 9.5% among young adults), and, according to the authors, these numbers have likely declined further with the rise of pods and disposables.

That weakens any easy extrapolation, and also reminds us that niches exist. And may deserve study, as long as the study clearly states what it’s doing.

The paper forces a practical question, one that precedes any regulatory slogan: when public policy leans on exposure studies, those studies must clearly declare what is being tested.

Is it typical use? Extreme but plausible use? Or a failure mode induced by lab parameters?

It’s legitimate to explore the edges. What’s not legitimate is to call the edge the center by inertia, or to describe it so incompletely that the reader assumes representativeness where there was only convention.

If this study leaves a legacy, it will likely not be a verdict on human risk, but a minimum technical standard of honesty, presented as a guideline.

The authors recommend pre-calibrating devices; state that the E-Vic Mini operates more efficiently and displays more accurate readings at airflow rates below 10 L/min, consistent with its direct-to-lung design; and suggest that, if the system remains restricted to low flows, experiments should avoid configurations that push it outside the Optimal Regime.

The moral, for regulators and journalists alike, is less about values than about method: be wary of firm conclusions when it’s unclear how the aerosol was actually generated, or when the experimental setup itself seems designed to trigger overheating.

In science, the most critical data point isn’t always in the graph. Sometimes, it’s in the setting just before it, somewhere in the air, the method allows through.

The problem of overheating in testing was first observed in a study published around 2015. The fact that this problem is still happening just shows how indifferent Tobacco Control is towards good science. Finding a 'scary problem' is far more valuable to TC than any concern for good science.