Paulo Freire can redefine Tobacco Control

In the cold early hours of São Paulo, a middle-aged man leans against the side wall of a public hospital. He wears an oversized coat draped over his shoulders. His shoes are worn. In his hand, he clutches a plastic bag that sometimes fills with wind like an improvised lung. Between coughs and shallow breaths, he lights a cigarette. He coughs, swallows hard, lights it again. Between his trembling hands, the cigarette goes out once more. He looks around. He looks into the bag. The gesture is almost clandestine. He carries medical test results in that transparent plastic bag as if transporting his own fate. Or sentence.

Still, he insists. After that glowing tip, he shrugs, brings his hands close in a gesture that borders on the liturgical, and inhales the smoke as if asserting a minimal autonomy—a choice that seems his alone.

He doesn’t know it, but in that moment, his life embodies the dilemma of an entire public policy. Brazil is an international benchmark in tobacco control: since 2005, when it ratified the World Health Organization’s Framework Convention, it has managed to reduce the number of smokers by millions. Adult smoking prevalence dropped from 15.7% in 2006 to around 9% in 2021, according to the Ministry of Health. The formula was multifaceted and relentless: tax hikes, a ban on advertising, explicit warnings on packaging, strictly smoke-free environments, coordination between government and civil society, and the provision of smoking cessation services through SUS, the Unified Health System—universal, free, and accessible to anyone at one of the 44,900 Basic Health Units spread across the country. A model praised by the United Nations.

And yet, there—within that body doubled over by coughing—the statistical success reveals its limits. Because every pedagogy, including that of health, can be either banking-style—vertical, imposing—or liberating, dialogical, freed from the logic of control.

The current paradigm of tobacco control—though grounded in solid epidemiological evidence—often operates through a top-down logic, focused on obedience and fear. Its actions are predominantly punitive, moralizing, or meritocratic: raising taxes, shocking with images, imposing cessation targets, and measuring success through charts. While statistically effective, these strategies frequently overlook the social and emotional complexity of dependence, reinforcing a model that treats the smoker as a failed patient rather than a subject of choices and contexts.

The foundation of this policy is rarely questioned: it rests on a notion of health as the absence of risk, as an ideal standard to be attained—rather than as a collective, situated, historical process. Its praxis, therefore, prioritizes prescription and surveillance over listening, mediation, and connection. This is the logic that must be redefined—and it is at this juncture that Paulo Freire can offer not just metaphors, but pathways.

And it is Paulo Freire—who never wrote a single line about tobacco—who may nonetheless offer us the lens to see what the smoke insists on concealing.

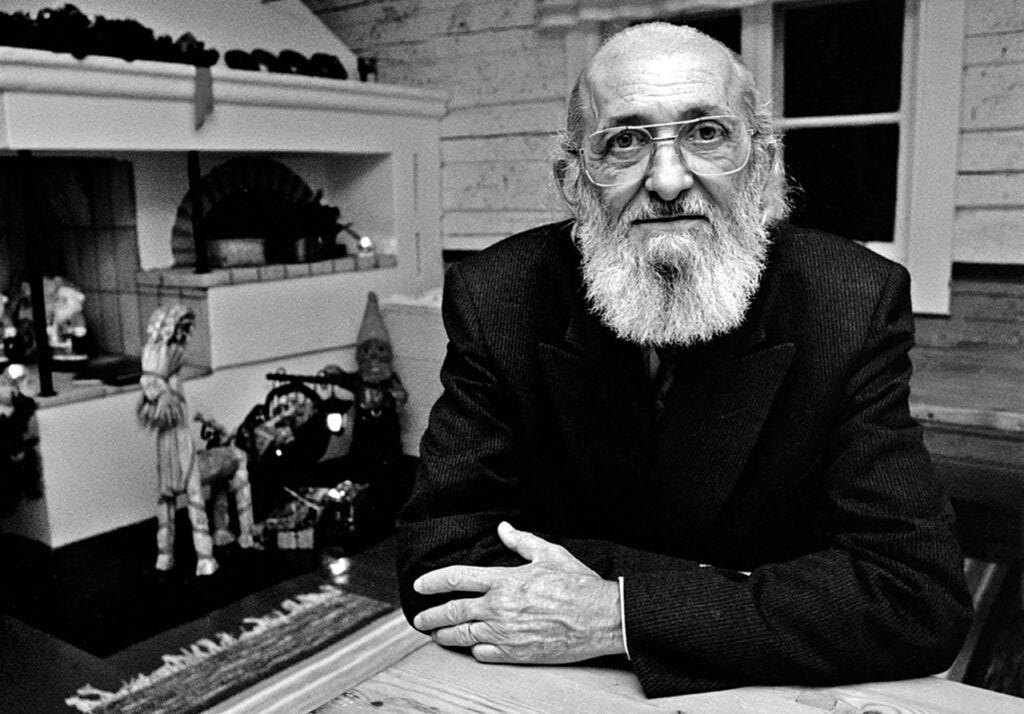

Paulo Freire (1921-1997) never mentioned cigarettes. But silence, in the pedagogy of this Brazilian educator and philosopher, is not emptiness—it’s an invitation. A gap through which to read the world as a text. And the cigarette, in this sense, is a word inscribed on the body. Not merely a vegetal byproduct in combustion, inhaled as habit, but also a social ritual, a global commodity, a symbol embodied in inequality.

It has crossed centuries. From Indigenous rituals to colonial factories, from Hollywood’s glamorous ads to the fear campaigns printed on cigarette packs. From one end to the other, it has become capital, oppression, pleasure, and profit. Always seductive. Always matching the desires—or the voids—it promises to fill.

If literacy was, for Freire, a practice of freedom, then so is health care. Because the way Tobacco Control addresses smokers is, inevitably, a form of pedagogy. “Smoking kills,” scream the packages. The sentence is true—but it doesn’t engage in dialogue; it passes judgment. It reduces the smoker to a vessel for medical orders. A “student” to be corrected.

And, as Freire warned, information without listening does not emancipate—it merely deposits. It's the banking model of education dressed up as public policy. The message arrives, but it doesn't take root—because it doesn't recognize the other as a subject of knowledge, but as a mistake to be corrected.

In the logic of harm reduction, the first step is not to forbid—it's to listen. To listen as an ethical gesture. As a political act. Because before any intervention, one must recognize the other as a subject of history.

What does smoking mean to you? A companion against loneliness? A fleeting pause in a routine of exploitation? A trace of class? A family inheritance? An improvised strategy against anxiety?

This gesture is ethical because it breaks the silence of stigma. It allows the smoker to stop being a problem to be solved and to return to being a subject—a historical subject, with desires, with contradictions.

Care, within this horizon, does not prescribe: it welcomes. It does not command: it asks. Because dialogue opens the possibility of another path.

That’s why Freire’s pedagogy is not just a metaphor—it’s a possible practice. And perhaps, a necessary one. To rebuild tobacco policy from the ground up, starting with encounters rather than imposition.

Freire taught: autonomy is not a starting point—it’s a conquest. The fruit of praxis, of reflection that transforms into action grounded in the world. In the field of tobacco, this means rejecting the tyranny of immediate abstinence as a universal measure of therapeutic success. Because every body has its own timing—and every subject, their own story.

To demand that everyone quit smoking at the same time, in the same way, is to ignore the deep layers of inequality. Some reduce gradually. Others turn to medical support. Some have easy access to medication and therapy. Others need lower-risk alternatives. And there are those who face long waits in the public health system, exhausting workdays, daily violence—making the cigarette one of the few possible forms of relief. Some have time and a support network; others are alone. Autonomy, in these cases, doesn’t arise from command, but from connection. It isn’t imposed—it’s cultivated.

Respecting that path is not a concession. It’s justice. It’s the politics of connection in action. Because autonomy here is not meritocratic individualism—it’s built on solidarity. A shared horizon where the individual does not walk alone: they walk with their community, supported by public policies that recognize and uphold them.

For decades, public health campaigns have treated the smoker as guilty. But for Freire, no action exists in isolation from its history. Guilt must be shifted—denaturalized.

The modern cigarette is a product of a State that sustains an industry which manipulated research, funded decades of glamorous advertising, and exploited the poorest as a captive market. Dependence is not merely chemical—it is also pedagogical, social, and political.

It is constructed—and for that reason, it can be deconstructed. But never through humiliation.

Critical consciousness is understanding that quitting smoking is not merely an individual decision. It is a collective act of insubordination in the face of a system that profits from vulnerability.

Each attempt, each pause, each reduction ceases to be a private act of will and becomes a word written against market-driven oppression. A statement—silent or explicit—that another path is possible. And necessary.

Distributing axioms, catchphrases, commands, pills, or nicotine patches is not enough. Technique without reflection is sterile. Freire reminded us: it is in praxis—the union of critique and action—that transformation is produced.

That’s why community dialogue circles can be just as effective as medication. Because there, in the collective space, each recounted puff becomes a generative theme—and more space for care. The cigarette emerges as memory, shield, symbol. Heard aloud and in company, the gesture transforms into critical reflection.

And from that reflection—slow, shared, constructed—may come the decision to reduce, substitute, or quit. Not as a medical imposition, but as co-authorship of one’s own care.

In Freire’s pedagogy, the generative theme is more than just a word or concept: it is a lived experience that, when named aloud, opens the path to critical and shared reflection. It is the moment when the everyday—so often taken for granted—reveals itself as a historical construction.

The drag that soothes, but also traps. The cigarette that protects, but isolates. The automatic gesture that carries memories, absences, and acts of resistance. When these contradictions are heard without judgment, they can become living questions—and, through them, the possibility of change.

“There is no neutrality in education,” Freire used to say. Nor is there in health. Every tobacco control policy is a political act: raising taxes, restricting advertising, regulating or banning reduced-risk devices, guaranteeing or denying free therapies—all of it is a choice, and every choice reveals a side.

To embrace Freire is to take a stand: for autonomy, for dignity, for life. Against a system that decides who gets to take risks and who must obey; who has the right to breathe as emancipation, and who only breathes under surveillance, according to their social class. A system that turns lungs into profit. That turns cancer into profit.

To educate is to choose. To care is, too.

In that same early morning, in front of the hospital, the man finishes his cigarette. He slowly crushes the butt underfoot and lifts his eyes to São Paulo’s almost gray sky. For a moment, he breathes without smoke. It’s not a victory. It’s not a failure. It’s a pause. It’s a possibility.

If Paulo Freire were there, he might say that every pause is a beginning—and that to breathe, in one’s own time, is an act of resistance in the shared air we all inhabit.

Paulo Freire's bibliography

Education as the Practice of Freedom (1967)

Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970)

Education for Critical Consciousness (1973)

Cultural Action for Freedom (1975)

Pedagogy in Process: The Letters to Guinea-Bissau (1978)

Literacy: Reading the Word and the World (1987)

Learning to Question: A Pedagogy of Liberation (1989, with Antonio Faundez)

Pedagogy of the City (1993)

Pedagogy of Hope: Reliving Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1994, with Ana Maria Araújo Freire)

Letters to Cristina: Reflections on My Life and Work (1996)

Pedagogy of the Heart (1997)

Teachers as Cultural Workers: Letters to Those Who Dare Teach (1997)

Pedagogy of Freedom: Ethics, Democracy and Civic Courage (1998)

Politics and Education (1998)

Critical Education in the New Information Age (1999)

Pedagogy of Indignation (2004)

Daring to Dream: Toward a Pedagogy of the Unfinished (2007)

Pedagogy of Commitment (2014)

Pedagogy of Solidarity (2014)

We Make the Road by Walking: Conversations on Education and Social Change (1990, with Myles Horton)

Absolutely fantastic blog. You write so eloquently, a gift I don't possess. There are so many paragraphs that those who smoke or who have smoked can relate to. The ongoing punishment and isolation of those who smoke, which now includes those who use vastly less risky forms of nicotine, is beyond dehumanizing; it is punishment for not acting the way someone else determines to be "wholesome." Another superb blog that brings the reader into deep thought and reflection.