Part I — The Smoke We Still Breathe

The WHO’s new report shows the world is smoking less — but also exposes a deeper struggle between science, morality, and desire.

From rise to decline, smoking has ceased to be just a public health problem: it has become a mirror of inequality, morality, and fear.

The World Health Organization’s new report shows that the world smokes less than it once did — yet the institution itself remains divided between science and morality.

It seeks to defeat what it calls an epidemic that may need, before a war, a deeper understanding.

On the surface, the numbers seem reassuring: there are fewer smokers than two decades ago.

But beneath the smooth curves of prevalence lies an ethical dilemma — between punishment and care, between prohibition and understanding.

The WHO’s new crusade reveals as much about tobacco and nicotine as it does about ourselves: our inability to accept that pleasure and guilt inhabit the same body.

Tobacco, once a source of pleasure, then of sin, and now of absolute risk, returns to the center of a moral dispute — this time as both umbrella and scarecrow.

The WHO wants to defeat it, but perhaps the real challenge lies elsewhere: to accept the difference between the substance and the product; to learn to save without humiliating, to regulate without punishing, and to recognize the use of nicotine — like coffee, alcohol, or cannabis — as part of the human condition.

The world smokes less — but still breathes smoke. The number of people who use tobacco has fallen from 1.38 billion in 2000 to 1.2 billion in 2024: 997 million men and 206 million women. Most people live in areas where the air is denser and incomes are lower in low- and middle-income countries.

It’s a celebrated decline — 120 million fewer smokers since 2010 — a drop that sounds like victory when pronounced in the auditoriums of Geneva. But behind the graphs, one figure lingers with the stubbornness of smoke that refuses to clear: one in every five adults on the planet still uses some form of tobacco.

That is the number drifting through the pages of the WHO Global Report on Trends in Prevalence of Tobacco Use 2000–2024.

At first glance, the message seems reassuring: the world is making progress. Until the next line takes the breath away, we are still far from the end of the epidemic.

The word “epidemic” plays a role here that is more political than technical.

In the language of public health, smoking does not spread like a virus: there are no sudden outbreaks, no explosive curves of contagion. Tobacco belongs to another category — a chronic, persistent affliction without fever or quarantine, a global routine of dependency and inequality woven deep into the fabric of daily life.

When the WHO speaks of a “tobacco epidemic,” what it is really naming is a tragedy too stable to scandalize, yet too deadly to ignore.

WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus delivers the official line with the precision of a diplomat defending his institution: progress, he says, is the result of the control policies promoted by the WHO and adopted by many governments; the threat, instead, comes from an industry that “reacts with new nicotine products” and “targets young people aggressively.”

The tone sharpens. The call is urgent: act faster, act harder.

And just after that call to arms, the new battlefield comes into view. For the first time, the WHO measures the global use of electronic cigarettes.

The figure, announced with theatrical gravity, surpasses 100 million people: 86 million adults — mostly in wealthy countries that account for more than two-thirds of the total — and approximately 15 million adolescents between the ages of 13 and 15. Where data exist, the report adds, minors are on average nine times more likely than adults to vape.

The statement leaves no room for doubt: vapes, pouches, and heated-tobacco products “harm health” and are “fueling a new wave of addiction,” warns Etienne Krug, WHO Director for Social Determinants of Health, Promotion, and Prevention.

But what follows is not a verdict.

It is a story — global, unequal, politically charged — about how data and narratives compete to define the meaning of a molecule that has crossed centuries, markets, and moralities. And at the center of it all remain real people — bodies with biographies that rarely fit inside a graph.

What the Numbers Tell — and What They Don’t

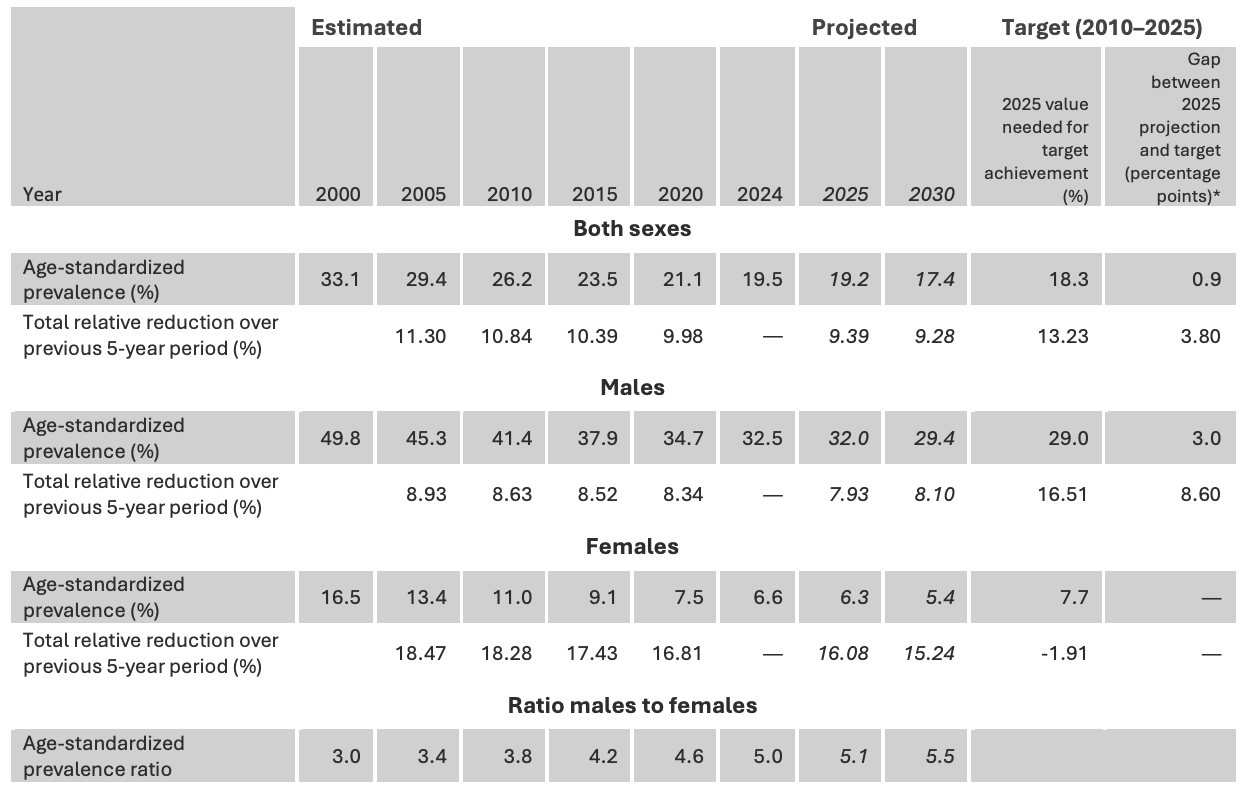

The historical series of the report traces two lines moving in opposite directions. The first is encouraging: the world smokes less than it used to. The second is more winding: those gains hide uneven rhythms — between regions, between genders, between individual lives.

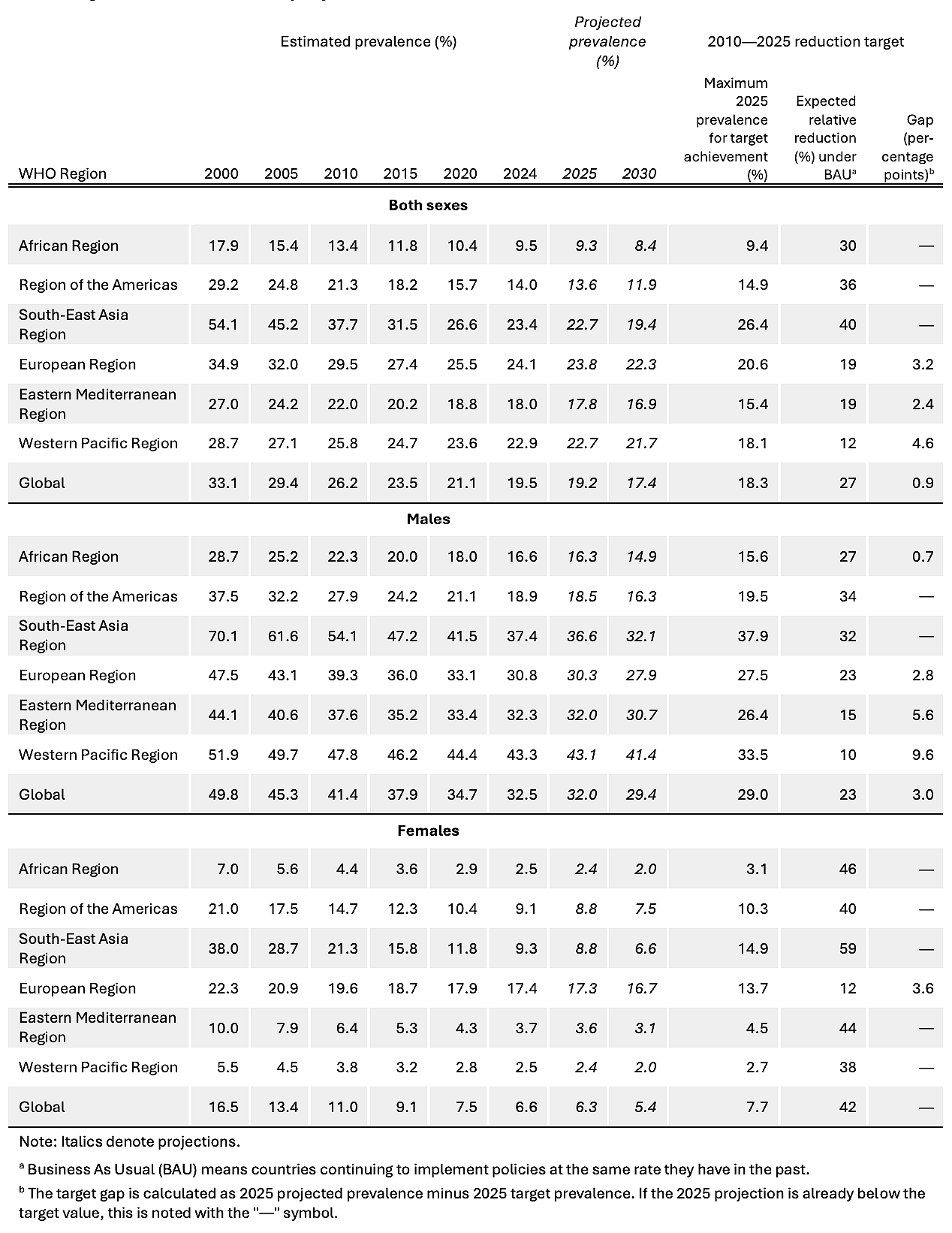

In South Asia and Southeast Asia — once the epicenter of global smoking — prevalence among men has nearly halved, from 70% in 2000 to 37% in 2024. That region alone accounts for more than half of the global decline, a feat the WHO itself celebrates as a milestone.

In Africa, the picture is more paradoxical. The continent shows the lowest prevalence of all regions — 9.5% in 2024 — and is on track to meet the 30% reduction target. However, statistical relief is not enough: as the population grows at breakneck speed, the absolute number of smokers continues to rise. Fewer people, proportionally; more people, in total.

Across the Americas, the prevalence has fallen to 14%, representing a 36% relative reduction, although data gaps persist in several countries.

Europe, by contrast, has become the new epicenter, with 24.1% of adults still smoking. And it is women who break the pattern — 17.4% continue to smoke, the highest female rate in the world.

In the Eastern Mediterranean, prevalence hovers around 18% and continues to rise in some countries.

In the Western Pacific, progress is slow, increasing from 25.8% in 2010 to 22.9% by 2024.

Men lead the statistics there with 43.3%, the highest male rate across all regions.

The gender divide speaks volumes.

Women have reduced tobacco use from 11% in 2010 to 6.6% in 2024, reaching the global target five years ahead of schedule in 2020. Their absolute numbers have fallen from 277 million to 206 million.

But men remain the heavy axis of the chart: nearly one billion smokers, more than four out of every five users. Their prevalence dropped from 41.4% to 32.5%, yet they are not expected to meet the target before 2031.

And amid the percentages, a footnote — easy to overlook — quietly changes the entire picture. The estimates are based on 2,034 national surveys covering 97% of the world’s population.

These are the data that feed the monitoring of the Sustainable Development Goals and the Global Action Plan for Non-Communicable Diseases, which aim for a 30% relative reduction by 2025.

The world has reached 27%. Fifty million people short of the goal.

And that is where the coldness of numbers begins to crack — when statistical success still fits entirely within human failure.

Three Analytical Warnings

First: proportion is not person.

Africa offers an uncomfortable lesson. The proportion of smokers is declining, but the absolute number continues to rise.

The math is simple; the drama is not.

When a population grows faster than its smoking rate declines, the result is a country that improves and worsens at the same time.

In public policy, less common does not mean fewer people. And when metrics dehumanize, politics loses the face of the problem.

Second: the word “addict.”

The WHO statement claims that “one in five adults remains addicted to tobacco.” But the data measure use, not disorder. It’s prevalence, not diagnosis.

The technical definition — the share of the population reporting daily or occasional use — does not imply a clinical nicotine dependence, which is a psychological condition with its own criteria.

Here, the word addiction performs a rhetorical function: it amplifies risk, mobilizes fear. It serves advocacy, but blurs the line between epidemiology, morality, and pop psychology.

In public health — and in responsible journalism — one must learn to tell the difference between a symptom and a sin.

Third: vaping and the “new wave of addiction.”

The WHO may be right to sound the alarm about youth use. No sensible argument defends early exposure to nicotine. But the science of e-cigarettes is far more nuanced than the panic/risk rhetoric allows us to see.

High-quality systematic reviews — such as those by the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group — indicate, with a high degree of certainty, that nicotine e-cigarettes increase quit rates compared with traditional nicotine-replacement therapies.

The problem is that evidence and policy don’t always breathe in sync.

Uncertainties about long-term effects — especially among youth who never smoked — are real; but so is the fact that millions of adults have stopped burning tobacco and seen their health improve thanks to a less lethal alternative.

Three warnings, then, that speak the same truth in different dialects: without precision in language, there can be no precision in care.

World Health Organization. (2025). WHO Global Report on Trends in Prevalence of Tobacco Use, 2000–2024 and Projections, 2025–2030 (6th ed.). World Health Organization.

Next: Between risk and relief, global health turns into a moral battlefield — where science, politics, and the human body collide.