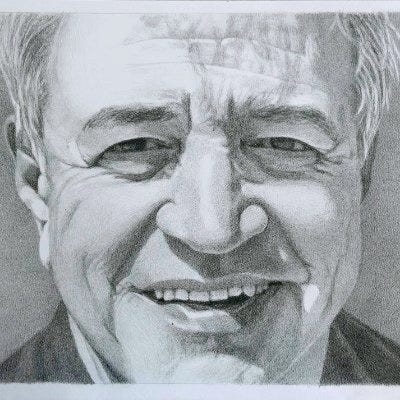

Beyond Willpower: A Conversation with Dr. Colin Mendelsohn

Dr. Mendelsohn, to begin our conversation, I would like you to give us an overview of the current landscape regarding tobacco use and efforts to quit smoking. Based on your clinical and scientific experience, how have the available treatments evolved, and how has the medical community—and society at large—come to perceive this issue? What would you say have been the most significant advances, especially with the emergence of the harm reduction strategy?

The current state of smoking cessation treatment can be described, in a word, as disappointing. Despite decades of research and clinical practice, the success rates of conventional treatments remain very low. Even in randomized clinical trials—the gold standard in medical research—the best available medications yield only modest outcomes.

According to the 2023 Cochrane report¹, after six months, success rates range from just 8% with nicotine patches to 14% with varenicline. In other words, over 85% of smokers continue smoking even with the most effective treatments. Furthermore, among those who manage to quit, relapse remains a persistent obstacle. There are no proven strategies to prevent it², and data show that after four years, only 6% of participants in clinical trials remain abstinent³. In real-world settings, these figures are even lower.

Although behavioral support can increase success rates, the reality is that few people have access to this type of assistance, which makes the overall picture even more complex. And when it comes to smokers in vulnerable or marginalized situations, smoking cessation rates are even lower—highlighting the urgent need for more effective strategies that also address health and economic inequalities.

In this context, tobacco harm reduction emerges as an essential solution for those who cannot—or do not wish to—completely give up tobacco or nicotine. Products such as nicotine vaporizers, heated tobacco, and nicotine pouches should be made available as complementary options alongside traditional cessation approaches. Each individual responds differently to treatment, which makes it crucial to offer a diverse range of alternatives, allowing people who smoke to choose the option that best suits their needs.

You have made clear the clinical limitations of current treatments and the need to offer more effective alternatives. But beyond the therapeutic approach, would you say that our understanding of smoking has changed? How has the perception evolved, both in society and within the medical community?

Tobacco use remains the leading preventable cause of disease and death worldwide, and yet it is often overlooked by both governments and healthcare professionals. One reason is the low efficacy of the available treatments, which may lead many professionals to believe that their time would be better spent addressing other issues.

I believe we have reached a point where treatments focused exclusively on abstinence are no longer sufficient. These methods address withdrawal symptoms and cravings only in the short term, but they fail to confront the behavioral dimensions of smoking and the persistent desire for nicotine. This is why products such as electronic cigarettes and heated tobacco have proven effective: they replicate the behaviors and sensations of smoking, and they deliver the nicotine that smokers need, while also helping to prevent relapse through prolonged use.

We also now recognize that some individuals require long-term nicotine use. Safer delivery systems—such as nicotine pouches or Swedish snus—offer a secure way to maintain such consumption. However, persistent prejudice and misconceptions about these reduced-risk products continue to hinder their widespread adoption.

This brings us to the role of healthcare professionals. In a context where scientific consensus on harm reduction is growing and the complexity of tobacco dependence is increasingly acknowledged, what would you say are the main challenges that physicians face today in clinical practice?

Healthcare professionals today are overwhelmed by an enormous volume of information and multiple competing priorities, which often makes it difficult for them to stay up to date. Tobacco use is just one of many critical conditions requiring their attention, and most professionals also face chronic time constraints. Addressing smoking requires time, and healthcare providers often—erroneously—assume that smokers lack the will or capacity to quit.

Although knowledge about tobacco dependence has expanded exponentially, much of this information has yet to reach frontline medical practice. Training for healthcare professionals remains an urgent and fundamental challenge.

Furthermore, healthcare providers have shown significant resistance to accepting tobacco-related harm reduction, despite the growing body of evidence supporting this approach. This must change, as harm reduction holds tremendous potential to improve public health and provide better outcomes for smokers who are unable to quit entirely.

Dr. Mendelsohn, let us now turn to the role of nicotine—a substance that is often misunderstood or misrepresented. Based on your experience, how should physicians understand nicotine within smoking cessation treatment, especially in the case of patients who are unable to fully give it up? And how does this perception change depending on the clinical or cultural context?

The evidence is clear: although nicotine can be addictive, it is a relatively benign substance. Its risk to users is very low, and in some cases, it may even provide significant benefits.

For decades, we have known that “people smoke for the nicotine, but they die from the tar,” as Russell noted in 1976⁴. This means that nicotine itself is not the cause of cancer or lung disease, and its involvement in cardiovascular disease is fairly limited.

While the ideal scenario would be for individuals to completely cease using nicotine-containing products, for some former smokers, maintaining long-term nicotine use is an effective strategy for preventing relapse into smoking. Tobacco harm reduction focuses precisely on this: replacing cigarettes with less harmful forms of nicotine consumption, such as vaporizers, nicotine pouches, Swedish snus, or heated tobacco.

Continued use of these products is considerably safer than returning to smoking. Moreover, nicotine offers certain benefits that some users appreciate, such as pleasure, improved concentration, and relief from anxiety. It has also been scientifically shown to provide therapeutic effects in certain conditions, such as schizophrenia, ADHD, ulcerative colitis, and Parkinson’s disease.

It seems clear that the clinical role of nicotine has, for years, been distorted by misinformation. In your view, how do stigma and misconceptions affect both public perception and medical decision-making regarding nicotine-based therapies?

Because of its association with smoking, many people mistakenly believe that nicotine is the harmful component of cigarette smoke. In reality, nearly all the harm caused by smoking comes from the more than 7,000 chemicals and toxins released during the combustion of tobacco—not from nicotine itself—as demonstrated by recent studies, such as that of Khouja (2024)⁵. Various investigations, including the study by Steinberg⁶ published in 2020 in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, reveal that both healthcare professionals and the general public wrongly believe that nicotine is harmful and causes cancer, among other health problems.

This misunderstanding has a troubling consequence: many healthcare professionals are reluctant to recommend reduced-risk nicotine products or nicotine replacement therapies, such as patches or chewing gum. Likewise, patients themselves hesitate to use these products and, when they do, often use them in insufficient doses or discontinue treatment prematurely—driven by exaggerated fears about the supposed harms of nicotine.

Studies such as that by Hannel⁷ in 2024 show that when these misconceptions are corrected, smokers demonstrate greater willingness to adopt such products, thereby increasing their chances of successfully quitting tobacco. For this reason, it is essential to eliminate misinformation about nicotine so that healthcare professionals can better support smokers in making informed decisions regarding the use of safer nicotine products and replacement therapies, ultimately contributing to improved public health outcomes.

This brings us to the myths and ghosts that persist, even in clinical settings. Based on your experience, what are the most persistent misconceptions surrounding smoking and nicotine? And how can we effectively dispel them, both in medical education and clinical practice?

Changing these misconceptions about nicotine has proven to be an extremely difficult task. In 2006, I co-authored an article aimed at correcting these false beliefs⁸, but unfortunately, little has changed since then. The article addressed nine widely held myths.

The first—and perhaps the most frequent—is the belief that nicotine is the most harmful component of cigarettes. While smoking is unquestionably dangerous, nearly all of the harm caused by cigarettes results from the chemicals released during tobacco combustion, not from the nicotine itself. Nicotine is not the most harmful component of cigarettes.

A related myth is the idea that nicotine causes cancer. This belief overlooks the fact that it is the toxins released during tobacco combustion that have carcinogenic effects—not the nicotine. Nicotine is not responsible for cancer in smokers.⁹

Likewise, there is a widespread notion that nicotine, by itself, is responsible for cardiovascular diseases. In reality, the major risk to the heart and blood vessels comes from regular cigarette use, which involves a combination of harmful agents. Nicotine does not cause cardiovascular disease in healthy individuals.¹⁰

The article also debunked the myth that smoking while using nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) is extremely dangerous and increases the risk of a heart attack. Even at that time, scientific evidence already demonstrated that NRT is significantly safer than continued smoking, even if the smoker does not immediately quit cigarettes. Smoking while using nicotine replacement therapy is not dangerous and does not increase the risk of a heart attack.

Other myths addressed the safety of nicotine replacement therapies. For instance, it was widely believed that using more than one form of NRT at the same time was unsafe. However, studies have shown that combining methods—such as nicotine patches and chewing gum—can, in fact, increase the effectiveness of smoking cessation without significantly raising the risks.¹¹ Using more than one form of NRT simultaneously is not dangerous.

Another common misconception was the erroneous comparison between NRT and cigarettes, particularly the belief that nicotine replacement therapies are as addictive as smoking. The article demonstrated that, while nicotine is indeed addictive, the level of dependence it produces is significantly lower in NRT forms, as they do not generate the rapid nicotine spike in the bloodstream that is characteristic of cigarettes. Nicotine replacement therapies are not as addictive as smoking.¹²

Perhaps the most alarming myths were those related to the use of NRT during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Many people believed that these therapies were as harmful as continuing to smoke during these critical periods, which discouraged many women from seeking safer alternatives. However, the evidence indicated that, although complete abstinence from tobacco and nicotine is ideal, NRT represents a far less harmful option than continued smoking during pregnancy or lactation.¹³

Finally, the article addressed the safety of using nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) in adolescent smokers—another highly controversial issue. The common perception was that these methods should not be recommended to young people. However, the reality is that for adolescents who had already developed nicotine dependence, nicotine replacement therapies offered a much safer alternative than continued cigarette use.¹⁴

Although our intention in 2006 was to dispel these myths using solid scientific evidence, progress has been slow. Deeply rooted beliefs are difficult to eradicate, even when faced with facts. It is essential that healthcare professionals have access to statements from independent and respected authorities, such as the Royal College of Physicians (UK)¹⁵, the Royal Society for Public Health¹⁶, Public Health England¹⁷, and the National Health Service (NHS)¹⁸.

Likewise, organizations such as the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC)¹⁹, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services²⁰, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM)²¹, Cancer Research UK²², and Health Canada²³ have explicitly stated that nicotine, by itself, does not cause cancer.

In addition to the aforementioned efforts, correcting these misconceptions requires placing greater emphasis on nicotine education—both in undergraduate medical training and in continuing professional development for healthcare providers. This knowledge is essential to equip physicians to better guide their patients, helping them make informed decisions regarding nicotine replacement therapies and reduced-risk products.

And part of that challenge, it seems, lies in language itself: in how we name and frame the use of nicotine. Do you believe it is essential to establish a clear distinction between “dependence” and “addiction” in the clinical context? And how might that terminological nuance shift the way we approach treatment?

The desire to consume nicotine in its pure form, as is the case with vaping, should not be strictly classified as problematic use, abuse, or—as it is popularly called—an “addiction.”

According to the Addiction Ontology, the term addiction refers to a compulsion to engage in a behavior known to cause serious harm to health. Under this definition, “addiction is a mental disposition that leads to repeated episodes of abnormally heightened motivation to engage in a behavior whose outcome entails significant risk or net harm.”

Nicotine, on its own, has minimal health effects, and the desire to vape is far more accurately described as dependence. Dependence is defined as the need to consume a substance to avoid the physical symptoms of withdrawal when its use is interrupted.

Furthermore, nicotine dependence is often overestimated. Other compounds present in tobacco smoke, such as monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), enhance nicotine’s addictive effects.²⁴ The speed with which nicotine is delivered through cigarettes also increases its dependence potential.

However, outside of tobacco smoke, nicotine has a much lower dependence potential. Products such as nicotine gum or patches present an extremely low risk of causing dependence,²⁵ and yet, some former smokers continue to use them long-term as a strategy to prevent relapse. Furthermore, tobacco dependence is intensified by behavioral, sensory, and social factors.

The use of terms such as “addiction” or “habit” carries a pejorative connotation and can promote negative attitudes and judgments toward people who smoke. In contrast, the term “dependence” carries less stigma, and dependence is a common phenomenon in our society, as seen with the consumption of caffeine or sugary products. If this term were adopted more broadly, healthcare professionals could develop a more empathetic and constructive attitude toward smokers.

Likewise, there is a clear double standard when comparing nicotine with caffeine. While nicotine dependence often elicits alarmist reactions, caffeine dependence is treated much more lightly. Caffeine is generally perceived as a minor cost in exchange for its benefits and pleasures, without the stigma associated with nicotine. Society, therefore, tends to tolerate the use of caffeine while demonizing nicotine, despite the fact that both substances share stimulant properties and can cause dependence.

Like nicotine, caffeine exerts stimulating effects on the central nervous system and can affect the cardiovascular system. Both substances also produce similar withdrawal symptoms—such as irritability and headaches—when their use is discontinued.²⁶ Studies conducted by Cappelletti (2018)²⁷ and Maessen (2020)²⁸ highlight that both caffeine and nicotine can be lethal in cases of overdose.

Caffeine is the most widely consumed psychoactive drug in the world.²⁹ Many habitual coffee drinkers experience withdrawal symptoms very similar to those caused by nicotine when they stop taking their daily dose. It is not uncommon to hear someone say they “can’t start the day” without a cup of coffee. It is important to emphasize that neither of these substances—nicotine nor caffeine—should be consumed by young people.

Not everyone wants to quit smoking,

but everyone deserves a safer option.

Dr. Mendelsohn, the concept of harm reduction is well established in other areas of public health, such as in the treatment of substance use disorders. What exactly does harm reduction mean in the context of smoking? How does it differ from traditional abstinence-based approaches? And why do you think this strategy continues to face resistance, even in some sectors of the medical field?

The traditional approach to smoking has always focused on abstinence—that is, the complete cessation of both tobacco and nicotine. However, success rates have historically been low, even with the most effective treatments. For many smokers, abstinence is not a viable option. Quitting smoking means giving up not only nicotine, but also the rituals and sensory experiences associated with smoking. Moreover, cravings can be easily triggered by everyday factors such as stress, coffee or alcohol consumption, or the presence of other smokers, making relapse a constant threat.

Harm reduction is a widely accepted and commonly used strategy in other areas of medicine, such as treating heroin users with methadone, needle exchange programs, or supervised consumption centers. It is also a well-established concept in public policy, as exemplified by measures such as mandatory seatbelt use in cars or helmets for motorcyclists. Harm reduction is a pragmatic solution grounded in the recognition that people will continue to engage in risky behaviors, and that the goal must be to minimize harm and prevent more serious consequences.

The reality is that many tobacco smokers are unable to quit completely. The harm reduction approach to tobacco use follows the same principles applied in other fields and serves as a complement to traditional abstinence-centered strategies. The aim is not to eliminate consumption entirely, but rather to reduce harm for those who cannot—or do not wish to—stop using tobacco or nicotine. This involves replacing cigarettes with non-combustible nicotine delivery systems that carry significantly lower risk.

Vaping products and heated tobacco deliver the nicotine that smokers need while replicating the behavioral, sensory, and social aspects of smoking. These alternatives serve as effective substitutes, particularly when smokers are confronted with triggers that would typically lead to relapse. Nicotine pouches and Swedish snus, in turn, deliver nicotine in isolation, without the additional harms associated with tobacco combustion.

It is essential to underscore that chronic tobacco users face an alarming risk: two out of three will die prematurely from smoking-related diseases. However, reduced-risk nicotine products can significantly lower that danger, offering a potentially life-saving alternative for those who struggle to quit smoking completely.

This pragmatic approach makes perfect sense. However, implementing it in clinical practice can present an entirely different challenge. What specific strategies would you recommend for healthcare professionals to incorporate harm reduction into their daily practice without losing sight of ethical considerations or the patient-centered approach?

The approach to treating tobacco dependence is, at its core, quite straightforward. Smokers who wish to quit should be encouraged to stop using both cigarettes and nicotine altogether, whenever possible. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that most smokers have already attempted to quit multiple times. On average, a 40-year-old smoker will have made more than 20 failed attempts to quit.³⁰ If smokers remain motivated to quit, the best available alternative is harm reduction, which involves switching to a safer and lower-risk form of nicotine use. This also applies to smokers who want to stop using cigarettes but prefer to continue consuming nicotine and maintain the behavioral aspects of smoking—without exposing themselves to smoke.

I firmly believe that physicians have an ethical responsibility to offer harm reduction options to smokers who are unable to quit entirely. They have a duty to provide the best possible treatment at each consultation, and denying a legitimate therapeutic option that could prevent a life-threatening illness constitutes a breach of that duty.³¹

Unfortunately, many physicians still lack adequate information about nicotine and the harm reduction approach, despite the growing body of scientific evidence supporting its safety and effectiveness.

Attitudes toward this strategy should be improved through ongoing professional education, which is essential to ensure appropriate patient care. It is crucial to offer a range of therapeutic options—both for those pursuing complete abstinence and for those who choose harm reduction. Patients respond differently to treatments and have diverse preferences.

As with any medical intervention, smokers need clear and comprehensive information about all available options in order to make an informed decision. Ultimately, the choice belongs to the patient, and the physician must respect that choice, even if the patient decides to continue smoking.

And how about the distinction between cessation strategies and harm reduction strategies? Based on your experience, what are the main differences between these approaches, both in terms of their goals and their methods? And how should physicians determine which one is best suited to each patient?

Smoking cessation therapies aim to eliminate tobacco use entirely, including both cigarettes and nicotine, usually within a few months. These therapies include nicotine replacement products—such as patches, gums, oral sprays, and lozenges—as well as medications like varenicline, cytisine, and bupropion. When combined with psychological counseling and behavioral support, these treatments typically yield the best outcomes.

Traditional harm reduction products—such as vaporizers, heated tobacco, nicotine pouches, or snus—can also be used as temporary tools during the cessation process. Smokers may choose to use these products and, when they feel ready, discontinue them—whether after a few weeks, months, or even years.

Harm reduction generally refers to the long-term substitution of combustible cigarettes with safer nicotine alternatives. While it is important to encourage patients to stop using any nicotine product as soon as possible, it is equally essential to recognize that, although harm reduction products are significantly safer than cigarettes, they are not entirely risk-free. Many smokers require continued use of some form of nicotine over the long term to avoid relapse, especially those with a high level of dependence.

Furthermore, some individuals choose to continue using nicotine because of its potential benefits. Nicotine has been shown to help manage certain mental health disorders by alleviating anxiety and depression. As previously mentioned, it also has therapeutic effects in conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia, ulcerative colitis, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

For many, nicotine provides a sense of pleasure and contributes to improved concentration and cognitive functioning. Some also find comfort in the ritual of hand-to-mouth action and in the social aspects associated with vaping or heated tobacco use. Although long-term nicotine use carries minimal risks, these are generally outweighed by the potential benefits.

The physician’s role is to provide accurate and comprehensive information about all available therapeutic options, enabling patients to make well-informed decisions.

Ultimately—and this must always be emphasized—the choice of how to quit smoking, as well as the decision to continue using nicotine in the long term, belongs solely to the patient.

In this regard, I would like to pause to focus on the tools currently available—particularly vaping products. You have already noted their potential. How are electronic cigarettes and heated tobacco functioning in real clinical contexts? Are there specific examples from your own practice that support their use?

Nicotine is undoubtedly a central part of the cigarette addiction problem, but paradoxically, it can also be part of the solution. Providing a safer and purer form of nicotine in the short term can help smokers quit cigarettes, and in the long term, it can serve as an effective tool to prevent relapse.

The available evidence indicates that nicotine vaping is the most effective form of nicotine therapy. The Cochrane review of randomized controlled trials concluded that nicotine vaping is 59% more effective than other nicotine replacement therapies, such as patches and chewing gum.32 Furthermore, other studies support this conclusion.

In my clinical experience, many smokers who were unable to quit using conventional treatments succeeded through vaping, and most of them reported significant improvements in their health. Although there is still limited robust scientific research on the effectiveness of heated tobacco products, anecdotal evidence suggests that these products have also been effective, helping millions of smokers distance themselves from conventional cigarettes.

Currently, there is a solid scientific foundation supporting the use of electronic cigarettes as an effective tool for smoking cessation. The Cochrane reviews of randomized controlled trials provide clear evidence that vaping is more effective than nicotine replacement therapies and at least as effective as varenicline (Champix).33

Furthermore, numerous studies—including observational research, population-level studies, and analyses of national smoking rate reductions—support this conclusion. Large-scale independent reviews have also confirmed that vaping is significantly less harmful than smoking, although it is not entirely risk-free, as demonstrated by the comprehensive studies of McNeill (2022)34 and NASEM (2018).35

While the ideal outcome is for smokers to quit both cigarettes and nicotine entirely, when this is not possible, vaping represents a valuable alternative. It can be used as a short-term cessation tool or as a long-term substitute for tobacco.

Vaping is particularly beneficial for smokers with higher nicotine dependence, who may need to continue using it. Furthermore, it offers an effective solution for individuals who are attached to the rituals and sensory experiences associated with smoking, as it closely mimics them. It also plays a key role in preventing relapse, especially in situations that trigger cravings, such as drinking coffee or experiencing stress.

Interestingly, vaping can be effective even among smokers who are initially unmotivated to quit. In many cases, simply trying vaping may lead to an unexpected transition away from tobacco—an outcome rarely observed with other cessation methods.

Moreover, although some individuals do not quit smoking entirely and continue with dual use (both tobacco and vaping), most of these users significantly reduce their exposure to the harmful toxins found in tobacco smoke. This means that even in such cases, vaping provides substantial health benefits. Of course, the ultimate goal should always be complete smoking cessation whenever possible.

Prescribing is not about imposing.

It’s about opening possibilities through active listening.

Dr. Mendelsohn, initiating treatments such as varenicline or bupropion, often marks a turning point in the process of quitting smoking. From your experience, when do you consider it appropriate to introduce pharmacological therapy? And how should that decision be tailored to the patient’s profile and specific circumstances?

There is a broad range of pharmacological therapies available for smokers who are dependent on nicotine, and all of them should be considered as part of a comprehensive treatment plan. These medications are designed to reduce withdrawal symptoms and cravings, thereby increasing the likelihood of success in the cessation process.

Nicotine dependence is generally identified in smokers who have their first cigarette within 30 minutes of waking or who smoke more than 10 cigarettes per day. In such cases, alongside nicotine replacement therapy, the main medications used include tablets such as varenicline, cytisine, and bupropion. Among these, varenicline and cytisine have been shown to be the most effective.

These treatments are valuable tools, but they are not without side effects. How do you recommend that physicians address this issue with their patients—without creating fear, but also without minimizing the risks?

All medications can present side effects, and it is essential for the physician to discuss them openly with the patient. For example, varenicline is well tolerated by most users, although approximately 30% may experience mild nausea, which generally subsides over time. Other side effects include headaches, insomnia, vivid dreams, and drowsiness. However, recent studies have confirmed that varenicline does not negatively impact mental health, contrary to earlier beliefs.

On the other hand, bupropion can cause side effects such as insomnia, headaches, dry mouth, nausea, dizziness, and anxiety. In rare cases (approximately 1 in 1,000), bupropion may trigger seizures, so it should be avoided in individuals with a history of seizures or those at elevated risk. Caution is also advised when prescribing this medication to patients taking other drugs that lower the seizure threshold, such as antidepressants or hypoglycemic agents.

Although serious side effects are rare, they must be weighed against the far greater risk posed by continued smoking. If a patient has previously used a medication with good results and tolerated it well, it is advisable to use the same treatment again. A common mistake is failing to complete the full course of treatment; ideally, therapy should last between 8 and 12 weeks, with the possibility of extending it in some cases.

It is clear that prescribing a treatment is only part of the equation. What other factors should be considered when deciding which option is best for each patient?

The choice of treatment for each patient depends on several factors. First, it is essential to review the patient’s history with previous treatments. Assessing what has worked—or not—in the past is crucial. Did the patient experience side effects or allergies? Did they have a positive experience with any particular treatment?

Another key consideration is the efficacy of the treatment. Currently, the most effective treatments include nicotine vaping products, varenicline, and cytisine.36 Patient preferences should also not be overlooked. These may include objections to certain types of therapy, such as the discomfort of chewing nicotine gum—which can stick to dental prosthetics—or a preference for more discreet treatments. Additionally, some patients may lean toward therapies that replicate the act of smoking, such as vaping or heated tobacco.

Cost is another crucial factor. The treatment must be financially accessible to the patient. Are there subsidies or support programs available? Can the patient afford the treatment? Availability must also be taken into account, as not all treatments are authorized or accessible in every region.

Understanding the patient’s overall health conditions in detail is also essential. Some treatments may not be suitable for individuals with certain medical conditions. For example, oral nicotine products can cause acid reflux and are not recommended for those with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Similarly, bupropion is contraindicated in patients with epilepsy. On the other hand, nicotine may offer benefits for individuals with ADHD or other medical conditions.

Empathetically assessing the patient’s level of knowledge—or misinformation—is another key aspect. Many smokers reject certain treatments based on misconceptions, such as the belief that nicotine is highly harmful or the idea that varenicline may induce mental health disorders. It is also critical to consider potential drug interactions. For instance, bupropion can interact with other medications, which must be taken into account when selecting the most appropriate treatment.

In clinical practice, the physician reviews all of this information with the patient, but the final decision always belongs to the patient. In many cases, the patient’s previous treatment history and individual preferences ultimately become the decisive factors in choosing the most suitable therapeutic approach.

This level of personalization seems essential. How can we ensure that the patient feels sufficiently in control to make their own decisions, without compromising firm and well-informed clinical guidance?

Treatments are more effective when the patient themselves makes the final decision about the approach to follow—and for that, they must be well informed. The physician’s role is to present the available options and provide clear and detailed information, explaining the benefits and risks of each treatment in order to guide and motivate the patient in their decision-making.

Moreover, it is essential that the physician responds to all of the patient’s questions with honesty and without judgment, offering ongoing guidance and support whenever needed. This consistent accompaniment ensures that the patient feels supported throughout the process, which significantly increases the likelihood of treatment success.

Even so, the abundance of options can be overwhelming for some patients. How can physicians act as true “curators,” narrowing down the alternatives to guide without imposing, and help the patient avoid paralysis from information overload?

The role of the physician is to guide the patient through the various therapeutic options available, clearly explaining the advantages and disadvantages of each treatment.

They should also recommend the most effective therapies and advise against those that may not be appropriate for medical reasons. For example, bupropion should not be used in individuals with epilepsy or those taking certain medications. Likewise, drugs such as varenicline, cytisine, and bupropion should be avoided during pregnancy.

However, as long as the chosen option is safe, the final decision must rest with the patient.

This approach not only empowers the patient but also ensures that their decisions are based on reliable information tailored to their specific situation. In other words, it respects their autonomy without relinquishing clinical guidance—an approach that ultimately increases the chances of success in quitting smoking.

Exactly. Once the treatment has been selected, the physician must adjust the nicotine dosage, as smokers with higher dependence may require higher doses. It is also essential to provide clear instructions on the correct use of nicotine replacement products and other medications.

Furthermore, an appropriate follow-up schedule must be established: smokers with high dependence or multiple failed quit attempts may require more frequent and extended monitoring. The physician should work alongside the patient to identify and manage tobacco use triggers—such as stress, alcohol or coffee consumption, and social situations involving other smokers—by developing coping strategies that help prevent relapse.

Providing additional support is crucial for smokers with strong nicotine dependence, those with mental health disorders, or individuals who use other substances. Finally, ensuring continuous follow-up and adjusting the treatment as needed significantly increases the chances of a successful smoking cessation process. These guidelines are essential to ensure the patient receives adequate support and to maximize their likelihood of successfully quitting smoking.

How can a collaborative, patient-centered approach improve adherence to smoking cessation treatment? And why is it so important to consider not only a therapy’s efficacy but also individual preferences when recommending it?

Quitting smoking is an urgent matter. For every year that a person continues smoking after the age of 35, they lose, on average, three months of life expectancy. For this reason, the ideal scenario is for smokers to choose the most effective treatment from the beginning and to aim to quit smoking as soon as possible.

This proactive approach can make a significant difference—not only in treatment efficacy, but also in the patient’s long-term health and well-being. By offering personalized support tailored to their specific needs, this strategy facilitates a more sustainable smoking cessation process.

However, efficacy is not the only factor to consider. No matter how effective a treatment may be, it will not work if the patient is unwilling to use it due to side effects, personal preferences, or financial concerns.

The physician’s role is to provide clear information about all appropriate treatments and to address any questions or concerns the patient may have. While the physician may offer recommendations and guidance, the final decision must always belong to the patient. Their commitment is essential. It is common to encounter patients who receive a prescription but do not use it due to doubts or concerns about the medication.

When patients actively participate in the decision-making process and fully understand all available options, they are more likely to engage with the treatment, thus increasing adherence to the chosen therapy. This underscores the importance of a collaborative approach between doctor and patient in achieving successful smoking cessation.

Relapse is not starting over: it is returning with more information

Dr. Mendelsohn, many smokers go through several failed attempts before successfully quitting, and that can be deeply discouraging. Based on your experience, how can physicians help reframe these failures as part of the process, thereby reinforcing resilience and increasing the chances of long-term success?

Most smokers go through multiple failed attempts before they manage to quit smoking for good. Over time, many abandon their efforts, convinced that they will never succeed. Some attribute their failure to a lack of willpower, but that is only part of the problem.

If a smoker is motivated to quit, the real key to success lies in proper planning, appropriate support, and the application of effective strategies tailored to each individual case. By offering a supportive and understanding environment, the physician plays a fundamental role in normalizing failed attempts as an inherent part of the quitting process.

So rather than viewing relapse as a setback, should we understand it as a natural—and sometimes necessary, even educational—part of the process of quitting smoking? What role does the physician play in conveying this idea without discouraging the patient?

It is essential to recognize that slips and relapses are a natural part of the quitting process. Rather than labeling them as “failures,” it is far more useful to consider them as “learning experiences.” Understanding why a previous attempt was unsuccessful can provide valuable insights for future efforts.

For instance, an attempt with nicotine gum may fail if the smoker does not use the correct daily dosage or is unaware of the proper chewing technique, which is crucial for the gum’s effectiveness. In a subsequent attempt, the treatment could be much more effective if used correctly.

Another example might involve a smoker who consistently relapses when consuming alcohol. Identifying this trigger makes it possible to develop strategies to reduce or avoid alcohol consumption during future quit attempts.

Stress is one of the most common causes of relapse. Learning to manage it and adopting preventive strategies can significantly increase the chances of success. Similarly, weight gain can discourage individuals who are trying to quit smoking. In future attempts, incorporating an exercise program and making simple dietary adjustments can help minimize this issue, thereby reinforcing the patient’s determination to stay on the path toward a smoke-free life.

The most important thing is not to give up. Each attempt is a learning opportunity, and the likelihood of success increases over time. If one strategy did not work, another should be tried. Identifying the causes of failure and, if necessary, seeking additional support is key.

It is never too late to quit smoking.

Slips—such as smoking one or two cigarettes—and relapses, where a person returns to regular smoking, are common during the first few weeks after quitting. These episodes often result from nicotine withdrawal symptoms and may indicate that the patient needs additional support or an increased dosage of medication.

Planning ahead is crucial for preventing these slips. Reflecting on potential triggers and preparing strategies to manage them—such as limiting coffee consumption, reducing alcohol use, or practicing effective stress management—can make a significant difference. It is especially important to avoid high-risk situations during the initial weeks. For example, if you associate smoking with drinking alcohol at social gatherings on Friday nights, consider skipping those events for a while.

And something very, very important: do not punish yourself if you slip! It can happen to anyone. Remind yourself why you decided to quit smoking—whether it’s to breathe better, improve your overall health, save money, set a good example for your children, or prevent serious illnesses like lung cancer.

The key is to recover quickly and avoid letting a slip turn into a full relapse. Consider the slip an opportunity to learn. What triggered it? How could you handle it differently next time? Reflect on what happened and reaffirm your commitment to your goal. If you are using medication to quit smoking, continue taking it—even if you have slipped. Keep using the nicotine patch, lozenges, or other treatments. Medication will help you regain control quickly and keep you moving forward toward a smoke-free life.

Let’s talk about preparation. When planning a process to quit smoking, how important is it for the patient to be mentally and emotionally prepared?

Quitting smoking is, without a doubt, a major challenge, and in some cases, it may be more appropriate to postpone the attempt if the patient is going through unusually high levels of stress. However, it is essential not to use stress as an excuse to indefinitely delay the process. Stress is a natural part of everyday life, and there will never be a completely perfect, worry-free moment to quit smoking.

For individuals with mental health disorders, it is advisable to stabilize their condition before attempting to quit. In such cases, having the support of a trusted physician or psychiatrist can be extremely helpful. It is common for anxiety and stress to intensify during the cessation process, with stress being one of the main causes of relapse. Therefore, it is crucial to reduce anxiety levels beforehand by adopting specific strategies.

Learning a relaxation technique, such as deep breathing or meditation, can be very beneficial. Engaging in regular physical exercise helps improve mood, relieve stress, and reduce nicotine cravings. Additionally, participating in relaxing activities such as yoga, tai chi, reading, socializing, or listening to music can also be highly effective. These practices can make the quitting process more manageable and help prevent stress-induced relapses.

Although nicotine helps relieve anxiety and improve mood—as noted by Benowitz ³⁷—the act of smoking itself also generates stress. This occurs because nicotine levels in the body drop between cigarettes, triggering withdrawal symptoms that increase anxiety and nervousness.

When smokers quit, these withdrawal episodes throughout the day disappear. In fact, research shows that smokers feel more relaxed and less depressed after quitting,³⁸ and they also experience a significant improvement in their quality of life⁽³⁹⁾. Explaining these benefits to smokers who feel anxious or stressed can be a powerful motivator to encourage them to attempt quitting.

One of the main advantages of vaping is that it allows users to continue enjoying the effects of nicotine without the harm associated with traditional tobacco use.

You have noted that proper preparation begins even before the actual quit date. In this context, what concrete steps should a patient take in the first 24 hours after making the decision? And how can physicians offer the best possible support during such a critical phase?

Ideally, the decision to quit smoking should be made with careful planning, allowing a few days for proper preparation. A helpful strategy involves conducting a thorough evaluation of the pros and cons of smoking, which serves to strengthen motivation.

This reflection process can be complemented by keeping a journal in which the patient records each cigarette smoked, the reasons behind it, and possible ways to avoid it in the future. This provides a clear understanding of personal consumption habits and allows for the development of more effective coping strategies.

Starting an exercise program can be extremely beneficial during this process. Regular physical activity is a powerful tool in the effort to quit smoking: it improves mood, alleviates anxiety, and helps manage stress. At the same time, it is important to consider other lifestyle changes that support this decision. Staying busy with new daily activities, adopting a healthier diet, and avoiding smoking inside the home or car are small steps that can make a significant difference.

Another factor to consider is reducing caffeine intake, as caffeine levels in the body tend to rise after quitting smoking. To avoid unwanted side effects, it is recommended to reduce coffee or other caffeine sources by half. Alcohol is also a common trigger for smoking, so avoiding it during the first two to three weeks after quitting is a prudent strategy.

Seeking social support is another key strategy for managing stress. Informing friends and family about the decision to quit smoking and asking for their support can have a very positive impact on motivation. Moreover, quitting smoking is a significant achievement, and setting small rewards throughout the process can help maintain focus and enthusiasm. These combined actions reinforce commitment and significantly increase the likelihood of success in the smoking cessation process.

Similarly, it is important to consult a physician to assess the need to adjust the dosage of other medications, as some may require modifications after quitting smoking. If pharmacological treatments for smoking cessation are being used, it is essential to begin the treatment in advance, generally one to two weeks before the planned quit date.

Another factor that may contribute to success is performing a deep cleaning of one’s daily environment. Consider thoroughly cleaning your home and car to remove the smell of tobacco, or visiting the dentist for a professional cleaning. These actions can reinforce a sense of freshness and renewal, providing additional motivation to maintain the commitment to quit smoking.

Choosing a specific quit date within the next two weeks can help maintain focus and provide mental preparation for the change. However, if you feel ready to quit immediately, it is important to act without hesitation in order to preserve the motivational momentum.

Be sure to dispose of all cigarettes—preferably by destroying them. Crushing them and flushing them down the toilet is an effective strategy to avoid the temptation of retrieving them from the trash. It is also advisable to remove ashtrays, lighters, matches, and any other objects associated with smoking in order to reduce temptation.

These actions help create an environment that reinforces commitment and facilitates the transition toward a smoke-free life.

The first week after quitting smoking is usually the most challenging, as nicotine withdrawal symptoms tend to peak during this period. Most relapses occur at this stage, making it crucial to use medication properly and at the correct dosage. If withdrawal symptoms become particularly troublesome, a dosage adjustment may be necessary under medical supervision.

Likewise, during this initial phase, it is essential to avoid personal triggers and high-risk situations—such as alcohol consumption—which can intensify cravings to smoke. For this reason, avoiding alcohol during the first few weeks may be an effective strategy for maintaining your commitment to quitting until you feel more confident and secure in your decision.

The first few weeks are often the most challenging. How can a patient prepare emotionally to cope with withdrawal symptoms? And which strategies have proven most effective for maintaining motivation and avoiding relapse?

It is essential that patients understand the process of quitting smoking and are prepared to face the challenges of the first few weeks. Withdrawal symptoms can be uncomfortable, especially in individuals with a strong nicotine dependence, and may persist for up to a month. However, it is important to remember that these symptoms will gradually subside over time, and persistence is key to achieving success.

The most common withdrawal symptoms include irritability, frustration, anxiety, difficulty concentrating, increased appetite, restlessness, depressed mood, and insomnia.

A crucial point is ensuring that patients are properly adhering to their treatment or using their medication correctly. A common mistake, especially when starting nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), is failing to use a sufficient amount of nicotine due to misconceptions about its safety. It is essential for patients to understand that, although nicotine is responsible for dependence, it is relatively harmless compared to other components in tobacco smoke. Nicotine must be administered in appropriate doses to effectively manage withdrawal symptoms and cravings.

The correct dose is the one that works for each individual, as some patients may require higher amounts than others.

Similarly, for those using electronic cigarettes, finding the right amount of nicotine is essential. Patients should experiment with different devices and nicotine concentrations until they find the combination that delivers the best result, including the flavor they find most satisfying.

This personalized approach can significantly increase the likelihood of success in the smoking cessation process.

Doctor, beyond vaping, patches, pills, or inhalers, what role does emotional support—often invisible but profoundly decisive—play in the process of quitting smoking? And how can one’s immediate environment become an ally, rather than an obstacle, in a battle that is so often fought in silence?

Although withdrawal symptoms decrease over time, cigarette cravings can persist for years. Therefore, former smokers must remain vigilant and prepared to cope with triggers, adjusting their daily routines to reduce the risk of relapse, as previously mentioned. Staying busy, managing stress, reducing the intake of alcohol and caffeine, and engaging in regular physical activity are key strategies to reinforce the commitment to quitting smoking and prevent relapse.

Quitting smoking can be an emotionally significant challenge for many individuals, and emotional support plays a crucial role in this process. The act of giving up tobacco can be overwhelming, and the support of a healthcare professional, family, or friends can be decisive in overcoming those difficult moments.

Strategies such as regular physical exercise, relaxation techniques, yoga, reading, music, and professional psychological support are especially beneficial, particularly for individuals with mental health issues. These practices not only help manage stress but also offer healthy ways to cope with the emotions that arise when quitting smoking.

Regular medical consultations can be of tremendous value. Healthcare professionals can offer practical advice, reinforce the patient’s confidence, and provide consistent support. A positive approach and close follow-up can make the difference between achieving success and experiencing a relapse.

Moreover, relapses should be understood as a normal part of the smoking cessation process—not as failures. They are a common occurrence in attempts to quit smoking and should be treated as learning opportunities. The most important thing is not to give up: to learn from mistakes, adjust strategies, and keep trying until the ultimate goal of permanently quitting tobacco is achieved.

The hardest part isn’t the first day. It’s the third cup of coffee, the first evening alone, or Friday night with friends.

Dr. Mendelsohn, one of the most critical stages in quitting smoking is the first week, when nicotine withdrawal symptoms peak. Based on your experience, do these symptoms vary depending on the method used? And to what extent is it possible to reduce their impact by combining tools—such as nicotine gum and e-cigarettes? Finally, how can physicians help patients design a daily plan that anticipates and manages both the physical discomfort and emotional toll of this phase?

Most relapses occur during the first week after quitting smoking, typically due to the intensity of nicotine withdrawal symptoms. This is a critical period that requires the appropriate and consistent use of medication or the selected treatment.

While all smoking cessation medications help reduce cravings and withdrawal symptoms, it is important to acknowledge that some discomfort may persist even with proper treatment use. When using nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), it is essential to ensure that the patient receives an adequate amount of nicotine to effectively relieve symptoms.

An especially effective strategy involves combining nicotine patches—which provide a steady level of nicotine throughout the day—with a fast-acting form, such as nicotine gum or lozenges. For individuals with higher nicotine dependence, it is recommended to use 4 mg gum or lozenges instead of the 2 mg ones, ensuring that an adequate amount is used consistently throughout the day.

Similarly, if vaping is used as a cessation aid, it should be employed as frequently as needed to manage withdrawal symptoms, and the nicotine concentration must be sufficiently high. If the current device does not provide adequate relief, switching to a more powerful model may be necessary. Medications such as varenicline, bupropion, and cytisine are generally administered in fixed doses, but they can be combined with nicotine replacement products to maximize their benefits and help the patient navigate this critical period more effectively.

That combined approach seems particularly useful for those experiencing more intense withdrawal symptoms. In such cases, how much does adjusting daily habits and managing the environment influence the early stages of the process? And beyond pharmacological support, what practical recommendations do you usually give your patients during those first days to help them avoid relapse?

During this initial period, it is essential to avoid personal triggers and high-risk situations that may lead to smoking, as we have previously discussed. For example, if alcohol is a strong trigger, it is advisable to avoid drinking. Similarly, if coffee is closely associated with the act of smoking, it may be helpful to temporarily replace it with tea.

These small adjustments in daily habits can make a significant difference in overcoming this critical period and maintaining one’s commitment to quitting smoking.

Staying busy and relaxed is an excellent strategy for shifting attention away from the urge to smoke. In addition, it is crucial to remember the “not a single puff” rule: just one cigarette is enough to significantly increase the risk of a full relapse. This approach helps reinforce commitment and maintain control during the most challenging moments of the smoking cessation process. The urge to smoke is often triggered by specific situations, people, or emotions. Identifying these personal triggers and developing effective strategies to manage them after quitting is fundamental. Some of the most common triggers include drinking coffee, consuming alcohol with friends, being around other smokers, smoking after meals, and experiencing stress.

So, identifying these emotional and behavioral patterns is only the first step. But once patients are able to recognize them clearly, how can the cycle be broken? How can that awareness be translated into concrete, sustained action over time?

Recognizing these patterns allows patients to anticipate challenges and implement strategies that help break the association between smoking and daily activities. Cravings tend to intensify in the evening and during nighttime hours—precisely when relapses are more likely. For this reason, it is essential to apply effective strategies to manage them while maintaining focus on the cessation process.

As mentioned earlier, keeping a smoking diary can help identify these triggers. By anticipating difficult situations, patients can prepare a list of cigarette-free alternatives to implement when those moments arise. Fast-acting nicotine replacement therapies—such as oral sprays, chewing gum, lozenges, or inhalers—can also be highly effective in responding to these stimuli.

And when we talk about behavior —those almost automatic, deeply ingrained responses —what concrete tools do you offer to help the patient interrupt that impulse right at the moment it appears?

In terms of behavioral strategies, I propose practical approaches such as the following:

Distraction: Engage in an activity until the urge to smoke passes. For example, try going for a walk, washing the dishes, or practicing deep breathing. Try redirecting your thoughts by recalling why you chose to quit smoking or by visualizing a calming scene.

Avoidance: For particularly difficult triggers, such as drinking with friends, it may be advisable to avoid those situations during the first few weeks, until you feel more confident in your ability to resist the cravings.

Delay: Although the urge to smoke may feel intense, it usually peaks within 2 or 3 minutes. If you can postpone the action for 10 minutes—by performing a brief task, for example—the craving will most likely subside.

Escape: If environmental pressure becomes overwhelming, remove yourself physically. Go home, take a walk, or simply move to a different place to break the stimulus-response cycle.

Environmental modification: Smokers develop strong associations between certain contexts and the act of smoking. Changing seemingly minor routines—such as watching TV in a different room, sitting in a different chair, or using a different coffee mug—can disrupt these automatic associations with tobacco use.

These may seem like minimal, almost trivial changes. But in practice, they can have a real impact when it comes to reconfiguring deeply ingrained habits.

Exactly. Small changes like these can have a highly significant cumulative impact on the smoking cessation process, as they reduce exposure to conditioned stimuli and reinforce neuroplastic mechanisms. Let us now consider other evidence-based strategies to manage smoking triggers after quitting:

Morning routine: Start the day by taking a shower immediately after waking up, brushing your teeth, and going for a short walk. A nicotine mouth spray can provide fast and effective relief for morning cravings.

Coffee consumption: Reduce your coffee intake or replace it with tea, orange juice, or water. Change the place where you usually drink coffee to a smoke-free area. Distract your mind by reading the newspaper, doing a sudoku puzzle, or switching to a different coffee mug and brand.

Alcohol consumption: Avoid alcohol completely during the early stages of smoking cessation. If you do choose to drink, alternate alcoholic beverages with water to stay hydrated. Switching from one type of drink (e.g., beer to wine) can reduce associated cravings. If temptation increases, it’s best to leave early—or avoid the situation altogether.

Exposure to smoke: During the first two weeks, avoid places where people smoke. Visit smoke-free environments—such as libraries or movie theaters—to minimize exposure to olfactory triggers that may provoke a relapse.

Managing boredom: Prevent relapse by structuring your free time with planned activities. Create a list of leisure alternatives, such as starting a new hobby, engaging in physical exercise, or using tactile objects like stress balls to keep your hands occupied.

Stress reduction: Engage in regular aerobic exercise to modulate your stress response. Practice relaxation techniques such as diaphragmatic breathing or mindfulness meditation. One effective method consists of inhaling deeply through the nose and exhaling slowly through the mouth for ten consecutive cycles. If necessary, seek support from a qualified professional or evidence-based stress management resources.

Rewarding progress: Reinforce each smoke-free milestone with non-pharmacological rewards—such as buying new clothes or going to the movies. Celebrating small achievements strengthens motivation and reinforces the sense of progress.

Friends who smoke: During the first few weeks, limit contact with friends who smoke. Before social gatherings, take a nicotine lozenge or chew a piece of gum. Kindly ask others to smoke outdoors or away from you. Participate in smoke-free group activities, such as going to the movies. Increasing your socialization with non-smokers can serve as a powerful positive reinforcement.

After meals: Brush your teeth immediately after eating, clear the table, do the dishes, or go for a short walk to break the association between eating and smoking.

Managing smoking triggers while driving: Remove ashtrays and lighters from your vehicle, and clean it thoroughly to eliminate the smell of tobacco. Keep sugar-free gum on hand to chew while driving. Snacking on raisins or sipping water in small amounts can also help reduce cravings. Establish a strict no-smoking rule in your car, even for passengers.

Break time at work: Reframe work breaks as opportunities to engage in alternative activities, such as reading, practicing diaphragmatic breathing in a quiet area, or taking a short walk outdoors, to reduce stress-related triggers in the workplace environment.

During phone calls: Keep a notepad nearby to doodle during conversations. Answer the phone using the hand you used to smoke with, and position yourself in a smoke-free environment. This helps dissociate the act of talking on the phone from the habit of smoking.

Oral appetite substitution: Address the urge to put something in your mouth by chewing crunchy vegetables (such as carrots or celery), pickles, apples, or sugar-free gum. Hard candies can also serve as a low-calorie alternative to satisfy the oral fixation commonly associated with smoking.

These evidence-based strategies are designed to reduce exposure to high-risk stimuli through habit substitution and the removal of conditioned cues, leveraging neurobehavioral mechanisms that support long-term success in quitting smoking.

Dr. Mendelsohn, we have already discussed how demanding the early days of smoking cessation can be—both physically and emotionally. During this particularly vulnerable period, how important is it to maintain regular check-ins with a physician? And what kind of concrete support can these visits provide to prevent relapse before it even occurs?

Yes, regular medical follow-up visits after quitting smoking are an essential form of support, as they help sustain motivation and significantly increase the chances of success. This follow-up is especially important during the first few weeks of abstinence, when the risk of relapse is highest and additional support can make a substantial difference in the final outcome.

During these follow-up appointments, physicians should offer sincere praise and words of encouragement, acknowledging the patient’s progress and reinforcing the importance of their decision to quit smoking. Recognizing even the smallest achievements helps patients stay motivated and focused on continuing the process.

So… these visits are not limited to prescriptions or symptom tracking; they also become emotional touchpoints—moments when the patient feels heard and supported.

Exactly. Another fundamental aspect is addressing the smoking triggers. The physician should carefully review any slips that may have occurred and, together with the patient, plan more effective strategies to manage such situations in the future. Anticipating challenges and creating personalized solutions are key factors in achieving sustained abstinence.

Additionally, these follow-up visits should include a review of proper medication use and administration. The physician must ensure that treatments are being used correctly, check for any side effects, and evaluate whether adjustments are needed in the dosage of nicotine replacement therapy or other medications. All of this ensures that the patient receives optimal pharmacological support to prevent relapse.

And what other aspects should be considered during these appointments, beyond the obvious clinical checks? What should the physician pay particular attention to?

Another important aspect is assessing improvements in the patient’s physical and emotional well-being. The physician may discuss with the patient any positive changes they have noticed since quitting smoking, thereby reinforcing the benefits of the process. It is also important to monitor potential weight gain associated with abstinence and provide recommendations to help keep it under control.

During the appointments, the physician should emphasize the importance of not taking “even a single puff,” as even one cigarette can trigger a full relapse. Furthermore, patients should be encouraged to stay busy and physically active, as this not only helps reduce the urge to smoke but also brings additional benefits for overall health.

Adopting a “one day at a time” approach is also a valuable recommendation, as it helps the patient reduce pressure and focus on small daily achievements. This method makes the process of quitting smoking more manageable and less overwhelming.

Finally, the physician should schedule additional follow-up visits as needed to ensure the patient receives continuous support during this transitional phase. These regular appointments can be a decisive factor in the patient’s long-term success, providing the encouragement and assistance necessary to get through the most challenging moments.

Quitting smoking often creates unexpected gaps throughout the day—moments that were previously occupied by cigarettes. What’s the best way to fill that space?

Staying busy is one of the most effective strategies for people who are quitting smoking. Smoking often takes up a significant portion of the day, and after quitting, it’s common to suddenly face extra free time. For this reason, finding new activities to fill that time and to keep one’s mind off smoking is essential.

The ideal approach is to choose activities that are enjoyable and that help maintain focus and commitment throughout the day. A helpful suggestion is to create a list of things to do when boredom strikes. This may be the perfect opportunity to start a new hobby or take up a sport. It’s always a good idea to keep a book, magazine, or crossword puzzle close at hand. If you’re feeling restless, keeping your hands busy with a stress ball can be an effective way to relieve stress. Additionally, volunteering or helping someone is an excellent way to use time productively.

Staying busy clearly helps. A new routine helps. However, not all routines fit every life. How can doctors adapt these strategies for patients whose life context adds another layer of complexity?

Planning specific activities for moments when one used to smoke is also essential. For instance, if you had the habit of smoking after meals, try replacing that moment with brushing your teeth, clearing the table, or going for a walk. During work breaks, it may be helpful to use that time to read, practice deep breathing, or take a short walk outdoors.

Keeping busy not only helps to distract from cravings but also provides additional benefits for health and overall well-being. Doctors can assist in tailoring these strategies to the individual needs of each patient, taking into account their interests, lifestyle, and mental health conditions.

By offering ongoing and personalized support, healthcare professionals help patients develop more effective coping mechanisms—an approach that not only increases the likelihood of successfully quitting smoking but also promotes long-term holistic well-being.

Once cigarettes are gone, what can replace them during moments of stress or tension?

Anxiety is a common response when quitting smoking and can be part of nicotine withdrawal symptoms, although medication can help reduce these effects. Additionally, many smokers feel anxious at the thought of quitting cigarettes, as both the ritual of smoking and nicotine itself were often used as tools to relieve stress. Once smoking stops, that “tool” is no longer available, which can increase discomfort. Some individuals may also experience heightened anxiety due to underlying mental health disorders. In such cases, it is essential to plan ahead to manage anxiety and prevent a relapse.

And how does this type of preparation translate into practice?

There are many healthier and more effective ways to relax than smoking. Physical activity and exercise are an excellent starting point, as they naturally help relieve stress. If you already use an effective relaxation technique, keep practicing it. Enjoyable activities such as reading, socializing, or listening to music can also help calm the mind. Talking to trusted people, such as friends or family members, can be very beneficial. In some cases, seeking professional counseling is necessary to address emotional issues or learn more effective stress-management strategies.

If you have an underlying mental health condition, it is important to stabilize it before attempting to quit smoking. Consult your doctor or psychiatrist to ensure your medication is properly adjusted. Psychological support can also be a valuable tool during this process. Additionally, keep in mind that smoking reduces the levels of certain medications in the body. When you stop smoking, those levels can increase, which may lead to side effects. It is especially important to monitor medications such as clozapine and olanzapine. Consult your doctor to determine whether medication adjustments are needed before quitting tobacco.⁴⁰

When stress arises after quitting smoking, how can doctors intervene before it pulls the patient back into a relapse?

Stress is one of the main causes of relapse during the process of quitting smoking. However, since stress is an unavoidable part of life, the key lies in reducing its impact and planning ahead to avoid particularly stressful situations.

Although the process of quitting smoking may increase stress levels in the short term, pharmacological treatments for smoking cessation usually provide relief. Even more importantly, studies show that after quitting smoking, former smokers tend to feel less stressed and happier. In fact, contrary to popular belief, smoking is not an effective way to cope with stress—in reality, it worsens it.

That debunks a widespread belief: smoking doesn’t relieve stress—it feeds it.

There are many healthier and more effective ways to relax and manage stress during the process of quitting smoking. Physical activity, for example, is an excellent way to release accumulated tension and improve mood, as even light movement helps reduce stress levels.

Another helpful method is deep breathing, which can significantly reduce anxiety and generate a sense of calm.⁴¹ In addition, progressive muscle relaxation—which involves gradually releasing tension in different muscle groups—is also effective in relieving both physical and mental stress.⁴²

Meditation is another highly recommended practice, as it promotes a state of calm and helps focus the mind on the present moment. Activities such as yoga or tai chi combine physical exercise with relaxation techniques, providing benefits for both the body and mind. For many individuals, enjoyable activities like reading, socializing, or listening to music are excellent ways to divert attention away from stress and stay positively engaged.

Likewise, talking to trusted friends or family members can help relieve emotional tension by providing a space to share challenges and receive support. In more complex cases, professional help can be a highly valuable option. Psychological counseling, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), mindfulness, problem-solving strategies, and assertiveness training are effective tools for learning to manage stress in a healthy way.

Discovering which relaxation method works best for each individual—and beginning to practice it before quitting smoking—can make a significant difference. Preparing in advance to cope with stress in a healthy way greatly increases the chances of success in the smoking cessation process.

Dr. Mendelsohn, once the initial intensity of the quitting process has passed, many patients ask: Now what? When and how should they begin to reduce their use of nicotine aids such as patches or electronic cigarettes? What is the best way to taper off without jeopardizing the progress they’ve made?

Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) is typically recommended for a period of 12 weeks. After this period, treatment can either be stopped abruptly or tapered gradually, depending on the patient’s preference. Gradual tapering can be done by cutting the patches into increasingly smaller pieces (for example, two-thirds, then half, then a quarter) or by reducing the number of daily doses of nicotine gum, lozenges, or sprays.

And what if the symptoms return? Should patients push through or take a step back?

Some individuals may need to continue using nicotine over the long term. If they do not feel confident in maintaining abstinence or begin to experience withdrawal symptoms and strong cravings when attempting to reduce the dosage, continuing to use nicotine is a much safer alternative than relapsing and returning to smoking.

Over time, it may become possible to discontinue nicotine use entirely.

This must be especially relevant for those who have already experienced a relapse. Is there a way to protect oneself after discontinuing nicotine use?

After stopping nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), it is helpful to keep a fast-acting form of nicotine—such as lozenges, gum, or a mouth spray—on hand to manage potential triggers or high-risk situations that may arise.

And how does gradual reduction work for those using electronic cigarettes? Is it a different process?

For those using e-cigarettes, it is recommended to gradually reduce the nicotine concentration as they prepare to stop using them. This process is easier to manage with open-system vape devices, which allow for customized adjustments to nicotine levels. On the other hand, some users may need to continue using e-cigarettes long-term. This is a proven relapse prevention strategy and carries significantly lower health risks compared to smoking traditional cigarettes.

It’s not about quitting smoking.

It’s about learning to inhabit the body without it.

I would like to look a bit further ahead. What do you believe is coming next in the field of smoking cessation? Which developments could truly transform how physicians support their patients? And how can they prepare for this new scenario?

Over the years, traditional smoking cessation treatments have helped some individuals, but overall, the results have been discouraging. The most significant shift in recent years has been the emergence of tobacco harm reduction as a viable strategy, although it still faces resistance from certain authorities.

Safer nicotine products—such as patches, gums, vaporizers, and other non-combustible systems—have proven effective where abstinence-based methods have failed. In some cases, they have even saved lives. The evidence is now clear: these products are effective and carry only a fraction of the risk associated with traditional cigarette use.

While complete cessation should remain the ideal goal, it is not always a realistic target for all smokers. In such cases, the use of safer nicotine products—whether short- or long-term—should not be seen as a failure, but rather as an essential step in the journey toward quitting smoking.

Physicians have an ethical and professional responsibility to offer all treatment options that have been proven effective to their smoking patients.⁴³ As tobacco harm reduction becomes more widely accepted, I believe we will witness a significant decline in smoking prevalence across our societies.

To end on a more personal note: for someone walking that long and uneven path toward quitting smoking, what is the most important message you would like them to take with them?

Take it one day at a time. That is one of the most important principles. The path to quitting smoking can feel long and difficult, and thinking too far ahead can be overwhelming. Focus on getting through today—this alone is a major achievement and deserves to be celebrated.