A Quantum Lens on Caffeine and Nicotine

Beyond Habit: What the Electrons Say

Amid the hum of daily life—where steaming coffee signals the start of the day and exhaled vapor merges with the unfolding routine—two compounds move unseen: caffeine and nicotine dwell within us, shaping mood, sharpening focus, and mediating dependence.

But what lies beneath, in the invisible depths of these substances?

Computational physics unveils new revelations about two of the world’s most beloved alkaloids, inviting us into the quantum realm—where matter dances to its own set of laws and simulation becomes a language capable of decoding what the senses cannot grasp.

There, at the crossroads of chemistry, computation, and the human body, emerges a molecular map that not only explains—but more importantly—provokes.

They inhabit our routines with the familiarity of an old gesture: in the energy drink that promises performance, the sugary soda that accompanies meals, the tea that soothes or stimulates, the transdermal patch meant to free us from vice, the over-the-counter medications bought without question or suspicion.

Caffeine and nicotine are perhaps the most intimate alkaloids of modernity—discreet yet persistent presences, woven into the social body with a naturalness that belies their power.

But their ubiquity should not dull our gaze: these are bioactive molecules, with effects as complex as their structures, whose impact—pharmacological, toxicological, and environmental—remains under scientific scrutiny, regulatory controversy, and public debate.

What happens if we stop observing these substances through their clinical manifestations or macro-social impacts and instead venture into the territory where everything begins: their electronic structure, their intimate vibration, their quantum “soul”?

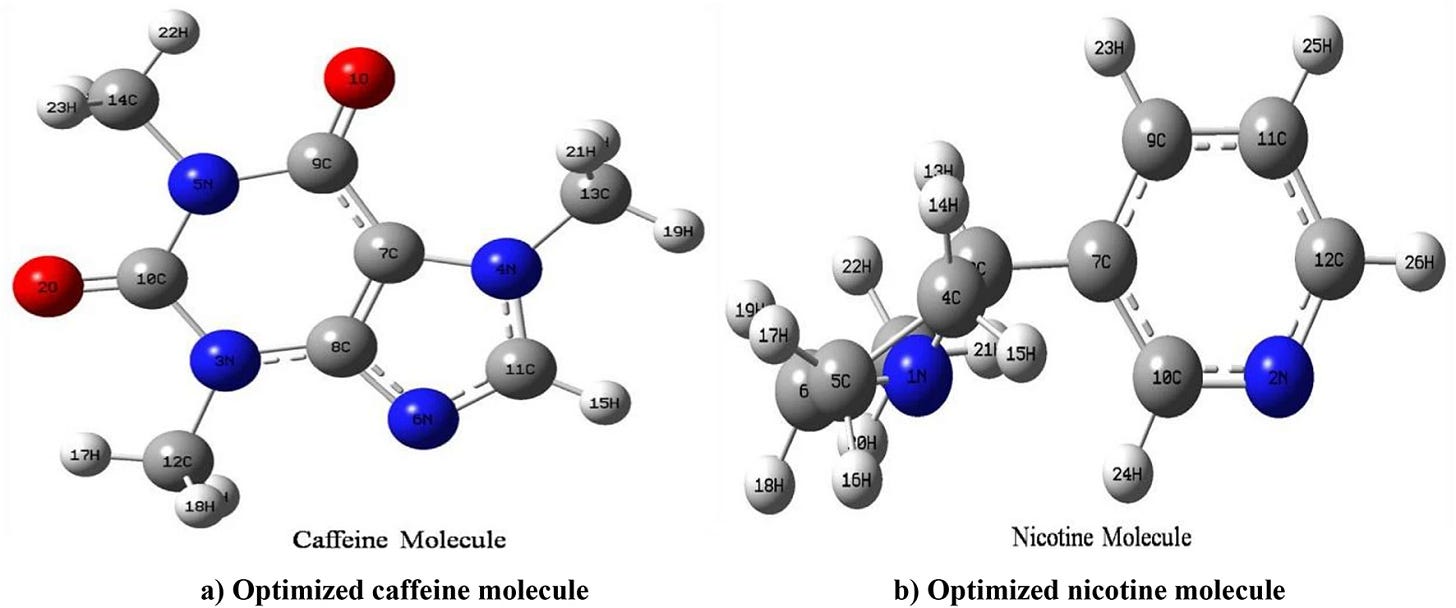

That was precisely the aim of a recent study published in Scientific Reports (2025), authored by researchers from Nepal and Ethiopia. Using tools from computational chemistry, the team led by Manoj Sah and Raju Chaudhary set out to meticulously map the molecular behavior of caffeine and nicotine across various chemical environments, laying bare their most elemental reactions.

The study's innovation is twofold and significant. Sah and his team, from St. Xavier’s College and Mizan-Tepi University, didn’t restrict their analysis to gas-phase or aqueous simulations, as many conventional protocols do. Instead, they modeled the behavior of caffeine and nicotine in two solvents with opposing polarities: carbon tetrachloride (CCl₄), a non-polar liquid, and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), a polar solvent widely used in biomedical research.

To achieve this, they employed advanced quantum models based on Density Functional Theory (DFT), which can unveil the electronic architecture beneath molecular appearances.

Thus, the team charted an atomic and optical map of these alkaloids, with ramifications—both conceptual and technological—that extend from computational pharmacology to the design of molecular sensors and nonlinear optical materials.

Molecules, Media, and Models

Though the names may sound foreign and technical, the study’s starting point is both simple and powerful: the chemical environment profoundly shapes how molecules behave.

To test this, the researchers used computer simulations that reveal how the structure and behavior of caffeine and nicotine shift across different environments. Rather than limiting themselves to air or water, as is commonly done, they also examined these molecules in two chemically distinct liquids: a non-polar solvent (carbon tetrachloride) and a polar one widely used in medicine (DMSO).

Thanks to computational chemistry tools such as Gaussian09W and Multiwfn, the researchers built three-dimensional models that reveal how these molecules change at the electronic level depending on their environment.

In doing so, the study offers a detailed, almost microscopic view that deepens our understanding of how these substances behave across different contexts.

However, as theoretical physicist Dr. Roberto Sussman (UNAM) rightly cautions, “these models must be verified in the lab and under real-world conditions, such as the actual delivery systems for caffeine and nicotine. Simulations do not replace experiments.”

His warning embodies a central tension in computational chemistry: its astonishing predictive power is inevitably accompanied by an epistemological caution that must not—and cannot—be ignored.

When the Environment Changes Everything

Among the study’s most striking findings is how the electronic behavior of these molecules shifts when moving from a non-polar medium like carbon tetrachloride (CCl₄) to a highly polar one like dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

Difficult names, yes. But the essential point is this: that simple change in environment is enough to alter how caffeine and nicotine distribute their internal charges, respond to light, and interact with their surroundings. In the molecular universe, context isn’t background—it’s center stage.

The dipole moment—which reflects how electrical charge is distributed within a molecule—increased significantly when the gas phase was switched to a polar environment.

Caffeine, with a higher dipole moment (4–5 Debye) than nicotine (3–4), showed greater sensitivity to its surroundings, partly explaining its high solubility in aqueous fluids such as those in the human body. That affinity is far from trivial: it shapes how these molecules dissolve, move, and operate within the biological environments that host them.

From an energetic standpoint, caffeine also demonstrated greater stability than nicotine across all simulated environments. However, both molecules experienced a loss of stability upon entering the liquid phase—particularly in DMSO—where electronic adaptation to the polar environment entails a significant energy cost.

In other words, integrating into the environment requires surrendering part of one’s internal balance: the molecule bends, adjusts, adapts—and in doing so, pays a price.

The Raman and UV-Vis spectra (“both used to study how light interacts with matter, but they measure different properties of light") also revealed striking differences between the two molecules.

Nicotine, with its more intricate molecular architecture, displayed a more significant number of vibrational peaks and a sharper spectral response to environmental changes. This sensitivity—almost tactile at the electronic level—suggests a particularly promising potential for use in optical sensors, where detecting the imperceptible is precisely the key.

However—as Roberto Sussman again cautions—these spectroscopic properties “are not necessarily preserved under real-world conditions, such as in a vaping device, which is a thermally open system with extremely rapid physical processes.” Indeed, a vaporizer does not replicate the quantum equilibrium conditions simulated by these models. This is why any extrapolation to applied contexts must be made with care: between theoretical prediction and real-world behavior lies an abyss of variables, fluctuations, complexities—and breathing bodies.

Light as a Probe

Where nicotine clearly outperformed caffeine was in its nonlinear optical (NLO) properties: total polarizability (α) and hyperpolarizability (β)—key parameters that define how a molecule responds to high-intensity light fields, such as those generated by lasers.

In this domain—especially in DMSO—nicotine exhibited remarkable optical reactivity, positioning it as a promising candidate for applications in photonics, optical data storage, and next-generation biosensors. In realms beyond human sight, these molecules might learn to see.

But again, nuance is crucial. As Sussman points out, “not every molecular reaction, no matter how sophisticated the modeling, can replicate the ultrafast, nonlinear physical processes that occur in devices like vaporizers.”

A hyperpolarizability simulated at rest—that is, calculated under ideal conditions, free from external disturbances or abrupt energy shifts—can behave quite differently when subjected to dynamic, extreme scenarios.

Intense thermal pulses, such as those generated in vaping devices, or rapid phase transitions (sudden changes in the system’s physical or chemical state), can drastically alter how a molecule interacts with light or its surroundings. Under such conditions, optical responses cease to be linear, stable, or predictable. This is why extrapolating from theoretical models to real-world applications cannot be taken for granted—it must be tested in concrete settings, where matter is no longer ideal and time does not stand still.

What the Unseen Electrons Reveal

The study also delved deep into the intricacies of electronic behavior, employing topological tools of high conceptual resolution.

AIM (Atoms in Molecules), NCI-RDG (Non-Covalent Interactions), and ELF/LOL (Electron Localization Function / Localized Orbital Locator) analyses enabled the visualization of weak intramolecular interactions—such as Van der Waals forces and hydrogen bonds—that support the three-dimensional architecture of molecules. Far from being mere mathematical abstractions, these methods allow us to observe how electrons are distributed across molecular space and how, from that distribution, subtle yet decisive forms of attraction emerge.

Though often invisible and easily underestimated, these non-covalent forces are fundamental to structural stability—they act as invisible threads holding the molecular fabric together. In this microcosm of delicate attractions, what appears secondary is in fact essential: it shapes, balances, and enables the molecule to be what it is.

In a polar medium like DMSO, these interactions intensify—the environment’s polarity reorganizes electron densities, reinforcing certain regions of soft bonding.

Such analysis is crucial for predicting how a molecule might interact with proteins, membranes, or biological receptors, where non-covalent forces are central to molecular recognition.

However, the study itself acknowledges its limitations: no explicit simulations were carried out with proteins, nor were cellular environments modeled. This omission narrows the scope for directly inferring complex biochemical behavior. As Sussman notes, “modeling how a drug affects protein structure requires additional, more specific simulations not present in this work.” Between what can be computed and what actually happens in the body, there remains a gap that simulation alone has yet to fully bridge.

Quantum Pharmacology and Predictive Toxicology

Although the study does not directly address toxicology or pharmacokinetics, its findings hold significant predictive value. Changes in molecular shape and charge distribution allow for informed hypotheses about how these compounds might behave in the human body: whether they dissolve well in water, how they might be broken down by enzymes, or how resistant they may be to metabolic processes.

In the domain of harm reduction, such simulations open a range of practical possibilities: predicting unwanted interactions with excipients, metabolites, or solvents; designing safer, less addictive molecular derivatives; establishing exposure thresholds based on real electronic properties. And not least, reducing the use of laboratory animals—aligning with the ethical principles of modern toxicology.

Still, caution remains a necessary compass. As Roberto Sussman reminds us, “these models are computerized representations of kinetic chemistry. Without practical validation under real-world conditions, their results are not enough to replace experimentation.”

His warning does not diminish the value of modeling, but insists on a science that doesn’t retreat into prediction—one that complements it, challenges it, verifies it. A science that doesn’t stop at imagining the possible, but dares to confront it with the real.

This study does more than dwell in abstract models: it proposes concrete uses with potential impact across disciplines—from science to industry to public policy. Possible applications include:

• Optical sensors that detect the presence of caffeine, nicotine, or other alkaloids in food, bodily fluids, or industrial settings.

• New materials for advanced optical technologies, including telecommunications, lasers, or data storage devices.

• Educational tools for teaching chemistry and spectroscopy more visually and accurately.

• Useful parameters for tracking and controlling substances in industrial processes.

• Monitoring systems for psychoactive compounds in the environment—potentially influencing health or environmental regulations.

In all these cases, the electron becomes not just a particle of matter, but a messenger of meaning.

Science with Awareness of Its Limits

This study stands out for its methodological rigor and original approach: it combines multiple tools from quantum chemistry to analyze two key alkaloids in chemically opposing environments.

But far from falling into the trap of overinterpretation, the authors display an uncommon critical awareness. They clearly acknowledge that the PCM model is a simplification, that only two solvents were explored, and that—no matter how promising—the results still require experimental validation before they can be confidently extrapolated.

It is science that moves forward, but without haste; that simulates, but does not delude itself.

Dr. Roberto Sussman’s critique—rigorous and grounded in the fundamental principles of physics—introduces a vital warning: the mathematical precision of a model does not, in itself, guarantee its validity in the real world.

Electronic devices, biological processes, experimental conditions—all contribute variables, fluctuations, and deviations that elude the control of any idealized environment.

To mistake formal accuracy for universal applicability is one of the subtlest—and most common—risks in the age of simulation.

Still, the article does not close doors—it opens them. It traces potential paths for future research and, above all, underscores the urgency of a collaborative science—one capable of crossing the boundary between the computational and the experimental.

Because only in that shared territory—where code and body, calculation and testing, meet—can we build knowledge with a true vocation for the world.

Conclusion: Understanding to Transform

The work of Manoj Sah, Raju Chaudhary, Suresh Kumar Sahani, Kameshwar Sahani, Binay Kumar Pandey, Digvijay Pandey, and Mesfin Esayas Lelisho goes beyond describing how caffeine and nicotine behave in different solvents.

It offers something more radical: a different way of seeing. A quantum lens laid upon everyday matter—one that transforms molecular complexity into practical knowledge, and the invisible detail into a possibility for action.

To look at the minuscule is not an escape; it is a form of intervention. The better we understand what inhabits us, the better we are able to imagine new ways of inhabiting the world.

In a discourse too often dominated by moral labels—where substances are judged more by their social stigma than by their molecular reality—this science reminds us of something essential: understanding is the first step toward transformation, and also the key to avoiding stigmatization.

To name with precision is to begin to see without prejudice. And to see without prejudice—perhaps—is the most radical form of knowing.

But this is not an empty promise. As Sussman aptly puts it, “quantum chemistry is a powerful tool, but no computational model can replace the complex reality of open, dynamic systems where these molecules actually operate.”

Between theory and practice, between electrons and public policy, this study marks a valuable—albeit early—step toward a more holistic understanding of substances that, precisely because they are so familiar, we often fail to examine with the depth they deserve.

Perhaps it is time to look at them anew—not as habits, but as molecular realities that challenge both the body and the mind, and the very ways we think.

Sah, M., Chaudhary, R., Sahani, S. K., Sahani, K., Pandey, B. K., Pandey, D., & Lelisho, M. E. (2025). Quantum physical analysis of caffeine and nicotine in CCL4 and DMSO solvent using density functional theory. Scientific reports, 15(1), 10372. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91211-9